Shanna’s father was psychic on paper. The first time she saw it, Shanna was eight and Dad sent her to the corner store with a list:

- skim milk

- barbeque chips

- Wait ten extra seconds after the light changes at Canal Street and Vine.

- toilet paper

- cereal (no sugar!)

It wasn’t that Shanna thought anything would happen. She wasn’t sure she thought much about it at all. She didn’t understand why Dad ate tuna fish with mustard, either, but she mixed it when he asked. Shanna counted (one Mississippi, two Mississippi…) as a young woman in squeaky shoes and an older man with a light ring of sweat at his collar jostled around her with twin glares. Even if she’d been crossing, she’d have been in their way: Dad always told her to walk, don’t run. Young Black people running made white folks nervous, and badges suspicious, and it was dangerous enough without that. At four Mississippi, Shanna noticed her left shoe was untied. At nine Mississippi she straightened up from tying a double knot.

At ten Mississippi, the red SUV ripped through the intersection. Squeaky Shoes and Sweaty Collar were on the other side; Sweaty Collar screamed out something Shanna wasn’t allowed to say and called the driver a maniac. Shanna crossed the third item off her list and debated whether Fruity Hoops were a sugar free cereal.

*

Shanna was twelve the first time she was out of school sick. She’d never missed a day before. It was hard to catch something when Dad packed her lunch with notes:

Avoid the water fountain outside gym class today kept her out of the line of fire when Felix Ditmier blew chunks. Switch seats with Carolyn Nettleford moved Shanna to the back of the class the day Mrs. Cho sneezed all over the front row.

“You’re lucky you only have a dad.” Nelson Parks came to walk to the bus with her the day Shanna cried stomach ache. “Moms always know when you’re faking.”

“Did she?” Shanna asked Dad when he checked her temperature.

“She who? And did she what?”

“Mom. Know when people were faking?”

“You need to drink water.”

Shanna let him leave because then she had time to hold the thermometer on her side lamp. When he came back, she worried she’d held it on too long, that Dad would scoop her up and run her to the hospital. She forgot to ask again.

The next day Dad wrote the note:

Please excuse Shanna’s absence yesterday. She was not feeling well, and I decided it best she stay home.

Her legs had the good kind of ache, the one that felt like stretching, when she held the note that had “s” in front of “he.” The one with the name she knew was hers but had never told anyone.

“How did you know?”

“Know what, kiddo?”

Shanna held the note up, paper crinkled in fingers that ached from clinging to it.

“Excuse notes were a thing even back in dinosaur days when I went to school.” Dad’s laugh had just that bit of rumble in it. He kissed her on the forehead. Shanna ran for the bus.

She shook when she handed the paper to Ms Garber in the school office, but Ms Garber glanced at it quick as she did anything, then shoved it in the file labeled with the name that wasn’t Shanna’s and issued the excused absence slip with the file’s name. Shanna had no trouble at all handing over that slip of paper. Because that one would wind up in the garbage, but Shanna was now part of her permanent record.

*

Shanna’s fourteenth birthday card came with a different bus number than she usually took. She had to leave for school early that day, but she didn’t mind after her regular bus broke down in rush hour traffic. Lunchbox notes avoided hallway spills. Valentine’s cards found Judy Edgarton’s pit bull. Whatever the notes said, though, Shanna learned just as much from them about the things people didn’t say.

Judy’s aunt, Ms Sanderson, sidled up to Dad at the bowling alley one league night. She giggled and played with her tawny hair and told Dad to call her Karen. He smiled, but his back locked up when she teased one glittery acrylic nail along his forearm.

Shanna had taken a break from the DDR in the alley’s small arcade and was so focused that Bento and Iria, laughing together on their way back from grabbing drinks, made her jump. They looked the most like twins when they were laughing. It put the same warm flush into their copper cheeks. Shanna didn’t usually like talking to grownups, but the Ramires twins were Dad’s best friends. Bento had even made Shanna flower girl when he married Paul.

“Doesn’t Dad think she’s pretty?” Shanna asked. Okay, they also twinned when that worry line showed up between their eyebrows, as they studied Dad and Ms Sanderson.

“I don’t have a note to give Karen. Did he give you one?” Bento asked Iria. She shook her head.

“What about you, Shanna?”

Shanna never forgot getting a note. “Only thing he wrote lately was the little bits for the homemade fortune cookies we brought.”

Bento and Iria knelt on either side of Shanna. She wasn’t sure if she liked the calla lily in Iria’s perfume more than the leathery musk of Bento’s, but they were both better than the nachos and old hot dogs that filled the rest of the alley.

“I know it’s not the last set, but I think maybe we do dessert early tonight. What do you say?” Bento whispered. Iria gave a wink. Shanna giggled at the conspiracy.

“Fortune cookies?” Shanna scooted up to Dad and Ms Sanderson with the basket. Ms Sanderson wrinkled up her button nose. Dad rubbed his forearm and gave the briefest shiver at the back of his neck.

“Homemade, Karen,” Bento said. “Even the fortunes.”

“Oooh!” Ms Sanderson snatched one from the basket, eyes locked on Dad. “You know what you’re always supposed to add to the end of a fortune?”

“What?” Shanna already knew the naughty version of that. Iria had told her. Which was probably why Iria giggled until Bento nudged her side.

“I … uh, well.” Ms Sanderson blushed and opened the cookie, then frowned. She gave Dad an entirely different kind of look before excusing herself to make a call. The next week Judy told Marianne Bixby how lucky her aunt was for making her mammogram appointment early.

*

Dad’s back locked up the same way later that year, at the science fair. Shanna had been wanting to introduce Dad to Mr. Gonzalez for months. He was her favorite teacher, and not for the reason Grace Hansen said—although it didn’t hurt that he had a lantern jaw and a beard trimmed just so and that lock of thick black hair that sometimes fell into his eyes so he had to blow it out of the way. He was smart and funny and nobody dared pick on anybody in Mr. Gonzalez’s class.

“Hell of a daughter you’ve raised.” Mr. Gonzalez shook Dad’s hand. “And all on your own.”

“Not all on my own.”

“Oh, you have a partner?”

“No he doesn’t.” Shanna put her hand on their still-held handshake. “And neither does Mr. Gonzalez, do you?”

There it was: the lock in Dad’s back and the shiver at his neck. No cookies this time, though, just the paper airplanes they’d folded for her presentation on aerodynamics. Shanna had made sure nothing was written on them. She’d even given the one with random numbers on it to Bento and Paul when they had been helping fold two nights ago.

“I … ” Mr. Gonzalez was even more adorable when he blushed. “My boyfriend and I did separate last year.”

“Jackpot!”

Dad broke the handshake at Bento’s yell from the cafetorium doors. Bento ran in waving a piece of paper with geometric folds all over it. The airplane.

“Bento?”

“I’m confused. And you are?” Mr. Gonzalez’s gaze ping-ponged from Dad to Bento to Shanna.

“Some of the help I was talking about,” Dad said. “With Shanna?”

“And if luck holds, the new school board president.”

“You said it cost too much to campaign?”

“16, 42, 8, 29, 63.” Bento waved the paper again, then hugged Dad so hard he lifted him in the air. “A five number lotto win, you beautiful man.”

“Congratulations.” Mr. Gonzalez had his own kind of locked-up look. “I should … I have to go get the kids lined up for their presentations.”

*

No one in the neighborhood knew Mr. Theodore was adopted, but it was a local postmark on the letter that pushed his long lost birth mother to call the day they all thought he’d be objecting to the bathroom policy the new school board enacted.

“I wonder what it’s like,” Shanna said. She and Dad were working on a jigsaw puzzle of Big Ben. Vanilla and brown sugar warmed the air from the cookies in the oven.

“What’s that?”

“Mr. Theodore. Getting to talk to his mom when he thought he never would.”

“Mr. Theodore got to talk to his mom every day growing up.” Dad kept studying the sides of his piece to check for a match in the black and white bits of clock face.

“I mean, his real m—”

“Real is where our hearts live,” Dad said. “Two people decide to raise a child together? They’re parents. Doesn’t matter what bits of goop got together to make the baby.”

Shanna clicked another piece onto the long border line she was building. “Did you and Mom always want a kid?”

The oven timer buzzed.

“Cookies!” Dad hopped up and scooted for the kitchen. “Don’t want to scorch another batch.”

*

When Shanna was seventeen, Mrs. Ditmier got a postcard with a picture of Hawaii on it. The address of her husband’s other wife was scrawled on the back. She handed off the prom committee to Mr. Sanderson, who was more than happy to sell Shanna her ticket, along with a free discount card to his sister’s dress shop.

“Any idea who you’re going to ask?” Dad folded towels on the kitchen table. The air swam with lavender.

Shanna squirmed. The ask was obvious. The answer wasn’t. They liked the same music and lent each other books. They agreed the tie-breaker between Ms Rosenfeld and Mr. Lau for cutest teacher depended on which blouse Ms R wore and if Mr. L had short sleeves that day. None of those were a dance. Shanna busied herself scratching at the little bit of leftover tape where the postcard from Hawaii used to hang on the fridge.

“Did you ask Mom, or did she ask you?” It was always better for Dad to squirm.

“She asked me,” he said.

“And?”

“And what?”

Normally Shanna wouldn’t press. But somehow the prospect of sharing this moment with Dad bubbled up Shanna’s throat until it tumbled out in a frantic surge:

“And how did she do it? Were there flowers? Witnesses? How did you feel? What did you wear? Was that the first time you kissed? Did you fall in love right away?”

“Was that the mailbox clanking?” Dad said. “Do me a favor and fetch it? I need to get dinner started.”

The grocery store had a heavy fan that kept bugs out when you walked through the front door. It pushed down on Shanna whenever she walked in, though she couldn’t push back. The silence as Dad got up from the table felt the same.

There was never anything for Shanna in the mail except on her birthday, but she flipped through it all the same. Bill, bill, flyer.

A letter addressed to her. In Dad’s writing.

She opened her mouth to ask, but the clatter of pans and utensils cut her off. She looked back down at the envelope, then scuttled to her bedroom.

Shanna crossed her legs on the bed. Slid a finger under the flap and ripped open the letter. A small key fell out as she unfolded the notebook paper.

Dear Shanna,

I’m making spaghetti for supper. I’ll need you to run to the store for grated parmesan in about half an hour. Until then, check out the lockbox under my bed?

She’d wondered about the lockbox, because she was a girl and not a goldfish. But she also wasn’t a locksmith, and there was only so curious to be about a metal cube. Besides, Dad hid the Christmas presents in his closet, not under the bed.

But notes changed things. Notes saved Shanna from sniffles and stomach bugs and locker room bullies and traffic. And notes lead to updated files, to tickets through a door, to treatment recommendations. To signatures on petitions and revised policy documents. Even when it wasn’t one of Dad’s notes, what got committed to paper shaped the world.

Shanna pinched her nose closed against the hoard of old sneakers Dad kept for yard work under the bed. Hooked the box with three fingers to half slide, half spin it across the bedroom shag into the light. Despite the note, she flinched at the squeak as she turned the key. Dad didn’t come to stop her, or Bento or Iria or Paul. She flipped the latches and lifted the lid.

The envelope said “Shanna” and had today’s date, though the number seven had a line through its middle, which Dad stopped using when Shanna was thirteen and told him it looked like he was punishing it by crossing it out.

Shanna slid her finger more delicately under the flap on this envelope than she had the first. The glue on the seal was old and dried. It didn’t so much rip open as strain and pop. There was a whiff of musty perfume that curled up and disappeared. The paper had curdled to cream over however long it had been inside, but the pen ink—in the same writing as on the envelope—was still dark enough to read.

*

Dear Shanna:

Today you asked how your mother and I got together. I’m sorry I was cross with you. I don’t want to lie to you, but I’ve never been good at saying true things. I wrote it down, instead.

We knew each other, your mom and me, as long as I remember knowing anyone, and the world assumed we’d wind up together. We never felt it, but it was easy letting them write our story that way until we knew how we did feel. And for whom.

The problem with letting everyone else write your story is the way it teaches us to tell each new person’s story as if we know them, too. Mom did that when she met Riley. He had a bright smile and an easy laugh and strong hands. They kept it secret because he was up for an overseas appointment. His PR manager said he should be single or married, but dating would make him look like a gigolo. The secret made it more romantic for Leanne.

Shanna hovered fingers over her mother’s name. She licked her lips, a salty line along her tongue, and closed her eyes. She whispered the name and hugged the warmth of that inside her. She turned her eyes back to the note before she let herself imagine Leanne’s voice or what names she might whisper.

I helped her cover, even wound up riding along on a few of their dates. Saw the way he didn’t argue when she called it love and snuggled up to giggle plans about the future, her fingers laced in his, a knot both tender and fast. Maybe he was like us. Maybe it was easier to fall into the story Leanne spun. He had a brilliant career ahead of him, so it was quite a story to be told. Maybe she could even have been part of it. It was not, however, a story he could tell with an unwed pregnant woman on his arm.

Leanne and I, though. Everyone already thought we were together. Thought we would always be together. Would it be so bad, she asked (when she could talk again without hitching sobs stealing her voice), if we were?

I didn’t answer that night. Didn’t say I couldn’t be the man she wanted. That she didn’t know me all the way through, because I’d kept that from her the same as anyone else. My heart doesn’t live there, in a world that yearns for clasped hands and whispered devotions and the tender caress of another.

It was too important, now, to keep hiding from her. But my throat closed up and my tongue swelled shut too tight to make the very first A sounds, let alone say asexual and aromantic. I decided to write it down. People talked all the time, but they listened when it was down on paper. Only, when I sat down, what I wrote was “This is the last year you will have with Leanne, and you won’t regret anything as much as if you abandon this time to fear.”

I showed it to your mom, and that’s how I found out I wasn’t the only one holding a secret from the other. She swallowed, loud. Took my hands in her shaking own. Told me it was true. As was everything I wrote after. Lists and notes and cards, all of it told us the truth even if we didn’t want to read it.

She did, your mother, want to read it. Especially about you. I told her I couldn’t promise it would shine with hope and joy, that ever since that day I couldn’t write a thing that wasn’t true. I didn’t want her to despair in the end if it all came out wrong.

“When the baby is born,” she insisted. “When there’s no more going back, I want to see everything that’s ahead, good or bad. If I were here I’d see it all anyway, but I won’t be here. Least I can do is to leave knowing. Promise you’ll have it for me.”

When she finished feeding you the first time, when we signed the paperwork that claimed you ours, she asked for it. In between feedings and diapers and her own coughing fits, she read what I had written. Read giggles and first steps and tantrums. The story of scraped knees and fights and fears and heartache, but also victories and triumphs and a community which was sometimes confused but always had a heart. I had written until my wrist was sore and the side of my hand stained with ink. Written more than I even remember, but know it was true, because I wrote her the story of you, and you are the truest person I know.

We buried it with her. I wrote it about you, but for her. So she could leave knowing, and we could be left to live it instead.

Now it’s Mom’s turn.

*

Shanna turned the last page over, holding her breath, but there was nothing written there by her mother. Nothing else in the envelope.

In the lock box, a single, faded piece of paper remained: her birth certificate. There was Mom, and there was Dad, but she flipped it over to dismiss the third name, the one that wasn’t hers, which is when she saw the name that was: Shanna. The S ballooned on its top half and flattened on its lower. The A‘s had that fancy curlicue on top like when you were typing. Handwriting that wasn’t Dad’s from then or now.

Under it, in that same style, said I don’t have your father’s gift, but I promise this is true: knowing the future doesn’t make you brave. Or strong. Or safe. Facing it is the way to have that. —Mom.

*

Shanna let Dad drag himself out from a deep dive in the fridge. He gave a huff and slammed the door. He took in breath to call out, turning toward the door, when his eyes fell on the cracked cream letter dangling in Shanna’s hand. Whatever he was about to say lost steam before he voiced it. His lips thinned, the creases on the side of his mouth deepening. The plop of simmering sauce filled the space between them.

“Grated parmesan?” Shanna asked. He hadn’t let out his breath until it rushed from him now. He opened his mouth, closed it. Nodded.

“We might be out,” Dad said.

“Won’t take a second to run down the street.”

“Walk. We don’t run.” Dad turned back to the pot on the stove.

Shanna folded the letter from the lockbox, stuffed it in her back pocket. She stopped half a step outside the kitchen, spun on her heel, and leaned back in the doorway.

“I’m going to ask Trini Walters to the dance,” she said. Dad smiled into the bubbling sauce.

© 2021 by Jaxton Kimble

3500 words

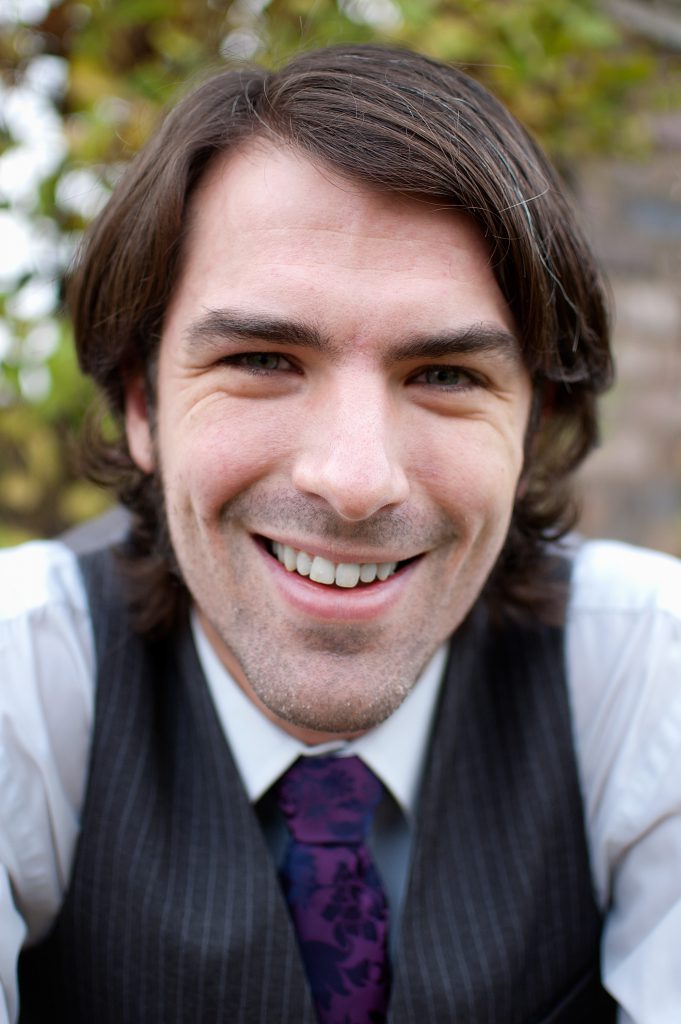

Jaxton Kimble is a bubble of anxiety who wafted from Michigan to Florida shortly after having his wisdom teeth removed. He’s still weirded out by the lack of basements. Luckily, his husband is the one in charge of decorating — thus their steampunk wedding. He has far too many 80’s-era cartoon / action figure franchises stored in his brain. His work has appeared previously or is forthcoming (as Jason and Jaxton) in Cast of Wonders, It Gets Even Better: Stories of Queer Possibility, and previously in Diabolical Plots. You can find more about him at jaxtonkimble.com or by following @jkasonetc on Twitter.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings. Jaxton Kimble’s fiction has previously appeared on Diabolical Plots: “Everything Important in One Cardboard Box” (as Jason Kimble).