edited by Ziv Wities

On a sunless morning, in the city of Astor, the word ‘caulk’ vanished.

The word didn’t announce its vanishing with trumpets or a booming clarion call. It faded away slowly in the middle of the night, like the last lyrics of a difficult song. The ones who didn’t use the word ‘caulk’ could not even tell what had gone wrong—the non-engineers, the artists and intellectuals—because for all intents and purposes, they would have spent their entire lifetimes not caulking anything.

Yes, the city of Astor simply woke up to unsealed joints in their stone buildings and leaking drainage pipes. The city woke up to a quiet mayhem.

Because with the word, the idea of caulking vanished too. And hence, near the harbours, the ships that had docked in the middle of the night, spewing sailors on the streets for a day of boastful extravagance, found themselves sinking, their wood coming apart at the edges. The groaning of the wood like a monster waking from slumber, the silent creaking like the hips of a man with an ill-timed squat, all these sounds fell silent as ‘caulk’ disappeared in a watery grave.

It took most of the day for the men and the women to unearth the caulk-shaped absence in their mind. Because just near the absence lay meaning, and meaning led to understanding. Understanding led to realisation that thankfully, only the word was gone, but not what it meant, not entirely.

With ‘caulk’ gone, ‘seal’ was used temporarily. But ‘seal’ was also used for other things, and lest the four letter word be burdened by too much meaning, a new word was thought of by the aging Keepers who sat in a dimly-lit alehouse drinking cheap rum, and thanking the heavens the idea of rum and the word still existed.

The word they came up with, a moustached man and an aunty who knitted sweaters, was ‘merk’.

“Merk?” asked a sailor, slamming a mug of beer on the table, froth spilling over and finding a new home amid niches carved in the wood.

“Merk,” said the aunty, admiring the pattern she’d made, as the ball of wool unspooled from her lap and hit the floor. “You can use it from now on. Tomorrow, someone from the Tapestry Collective will come and make the necessary additions.”

“Merk, instead of the word we lost. Now, I don’t remember what exactly that word sounded like, but it sure wasn’t ‘merk’. Merk doesn’t sound like it could fix all the joints in Astor.”

“It’s the best we could do,” said the man, swallowing his third shot of rum. “It was a well-used word, whatever it was, and disappeared with no warning. It takes a long time for us to come up with acceptable words.”

The old man’s answer was deemed acceptable. And so it came to pass, that merk took the place of the word everyone had forgotten.

But merk could hardly bear the weight of all the meaning the old word carried. There was no heft to ‘merk’. ‘Merk’ was a hasty concoction, a parody of a word, ironically meant to ‘caulk’ the joints between remembrance and essence, memory and context. The ships and the walls and the leaky sewage pipes learned soon, but it was never the same as before.

***

The man who’d come up with the new word was named Ullarian. And every morning, as he undid the blinds of his cottage-home snuggled at the edge of the forest, he would wonder if someone had forgotten the ‘sun’. Because Astor had never seen the sun, and while Ullarian knew that a sun existed in the sky, nobody in the entire city had ever mentioned the sun, or why a dull, perpetual brightness existed in the sky without the presence of a source.

When all the noise about merk had subsided, and the word found itself settling in the vocabulary of Astor, albeit uncomfortably, the old aunty from the bar visited Ullarian and gave him a sweater she had knitted, a bright crimson ‘U’ on the chest against a lime yellow backdrop. Ullarian accepted the gift with a warm smile and made spiced tea for the woman, whom he called Sultana, though in fact her name was something else, something even she had forgotten, but she accepted her new name, which dripped from Ullarian’s mouth like a waterfall, a name she liked.

Ullarian’s cottage was all wood, which made uncouth sounds all day long. But when Sultana sat with him near the window that overlooked the meadows, even the house consented to maintain an odd silence, respecting her presence.

“I am troubled,” said Sultana, stirring her tea, looking out the window. Ullarian was looking at the wrinkles on Sultana’s face, and how despite them, she looked ageless.

“What about?”

“There’s going to be another forgetting, and it will be bigger than what merk replaced. It could cause real havoc.”

“How can you be sure?”

“I don’t know, but these forgettings have been random and nonsensical. It will get worse. Small forgettings are always a precursor to big vanishings.”

“Then we’ll replace that,” said Ullarian. “Don’t you worry. That’s what we’ve always done. That’s what we did for brocken and semidifier and levertanum.”

“The ideas behind those words you just spoke, they were easy ideas. Easy ideas are harder to remove, because they contain multitudes of meaning. But what if we forgot tea? Would you wake up the next morning without the precise idea of brewing leaves in water?”

“Nobody wants that,” said Ullarian, taking a sip, and savouring it for a moment too long. “What do you suggest we do?”

“I want to visit the Tapestry,” said Sultana, her voice heavy.

“The Tapestry, on a hunch? Trust me, you don’t want to do that,” said Ullarian, sipping his tea. “Why don’t we wait for the Forgetting and see what we can do then, as we have always done?”

“You’ve grown complacent, Ullarian.”

“Not complacent,” said the man. “I just want to live the rest of my life in peace.”

Sultana sighed. And then said words which stung Ullarian.

“How are your bees?”

He knew what she was implying. Behind his cottage, he had constructed a small apiary. It was a small hobby he had acquired after Astor had lost the word for honey, and subsequently the substance itself. It was the only time in the history of Forgetting that Ullarian and Sultana hadn’t come up with a word. Instead, Ullarian had taken up beekeeping. Stacks upon stacks of brood frames lay in his backyard, where bees and their queen hatched from larvae and grew and grew and flew towards orchards to pollinate plants. When those bees created honey, slowly the meaning of the word found its way back in the folds of Astor’s brains, and when meaning came back, so did the word.

Even now, Ullarian could hear their silent hatchings. He shuddered to think of a world without bees. He winced. A shadow fell over Sultana’s face. She seemed to understand that she had taken it too far to prove a point.

Sultana finished her tea and left.

For five days, Ullarian did not visit the town. For five days, he lived cooped inside his cottage, thinking of what Sultana had told him, thinking of the meaning he had given to so many words before. Brocken, the word for a cuboidal piece of hardware that was used to store food-items, had come to him in a post-rum haze, when suddenly the town was plagued with food and liquid spilling all over the place with nothing to contain them. When that word was lost, suddenly its entire meaning was gone too. When the word was lost, a popular fight-sport vanished without a trace, with athletes suddenly finding themselves with bruised fists and muscular arms, and having no memory of how they got them.

Something had told Ullarian that the word started with the letter ‘B’, and the replacement would have to be something very close too, and not too far off.

For five days, Ullarian thought what word he might give to the bees, should they be forgotten. When he couldn’t come up with any, he packed his belongings, and made his way towards Sultana’s home.

Sultana lived on a cramped street where the road ascended towards a busier market area. The buildings were made of cement and stone and iron, and some of them were threatening to crumble because of merk not doing its job properly. When he reached the street, he felt disoriented. He looked up at the road as it disappeared in a flock of pedestrians eager to grab their morning coffee from cafes, their newspapers, and their chicken salami rolls. Ullarian felt an absence, but he couldn’t place it.

Sultana stepped out of her own blocky apartment, her keys jangling by a cord on her waist. She looked ready for a long trip, with one suitcase which threatened to rip at the seams, and one handbag, which was painted with all colours except one. When she looked at him, she smiled.

“I knew you’d come,” she said. “Always the light traveller.”

Ullarian looked at his own measly packings and wondered if he should have included his two sweaters and his three pairs of socks. The Tapestry sat at the top of a hill, and it could get cold that far up. But he shrugged off the thought as soon as he’d entertained it.

“Let’s go,” said Ullarian. “Before we forget the meaning of travel.”

***

Ullarian and Sultana began their journey on foot. First they crossed bright green meadows, rolls upon rolls of them, with silent footfalls and hushed conversation. They wanted to preserve their energy for the trip and the task ahead, and so as much as Ullarian wanted to talk and joke with Sultana, he kept his words locked inside him.

When the border of Astor became a memory on grass, they took a road paved on both sides with rocks and forgotten dung pellets. The road was smeared with muddy tyre tracks, which they followed until the asphalt became smooth again, and the surrounding meadows gave way to a rocky expanse, ending at the base of crooked peaks.

Ahead, the road ended where the edge of another city began, a city bigger than Astor, a city which housed the Ladder to the Tapestry. Instead of a gate, the city boasted a giant golden crescent, the higher tip of which rose fifty feet from the ground. When the crescent stood tall, its tip high above, the city was closed off to visitors. When it rotated, like a scythe pendulum, slashing the air with its brightness, it revealed the tall spires and interconnected buildings and most importantly, the Ladder it stood sentinel to.

Much to their chagrin, the city of Messan was closed. Despite it, however, they could see the gleam of the Ladder’s tip, thousands of feet in the air, where it met the pyramid which housed the Tapestry of Words.

“Is it happening?” asked Ullarian.

“Not yet,” said Sultana. “When it happens, you’ll know it.”

“Sultana, I’m scared. What if I forget my own name? What if the word ‘name’ itself vanishes?”

Sultana took Ullarian’s hand in hers. “I have the same fear. But at least we’ll be together in that forgetting.”

“I won’t recognize you,” he said. “I won’t even recognize myself. How are you certain it will be all right?”

“I am not,” said Sultana, calmly. Ullarian believed her. For the first time in her life, Sultana was unsure, and yet it didn’t seem to bother her. Had she, somewhere deep inside, accepted that the upcoming forgetting signalled the end of things?

He looked at the slate sky. No sign of the sun, and no clouds too. Both those elements, gone from the memory of Astor. Yet somehow, the city persisted. Maybe forgetting wasn’t everything.

Ullarian exhaled, and fog came out of his mouth. Messan was a cold city. They were a long way from Astor.

“Let’s go,” he said.

When they reached the Crescent Door, they met two tall guards, one dressed in silver, the other in gold.

“We are the Keepers from Astor,” declared Sultana. “We require passage to the Tapestry.”

“Why are you here?” The silver guard’s voice was mild mannered, but annoyed. “The Collective hasn’t yet made a decision whether they want to visit your city or not.”

“We are not here about the merk-seal,” said Sultana. “My Keeper partner has forgotten his name. This looked like an unscheduled event. That shouldn’t happen with Keepers. And I want to check.”

Sultana was lying through her teeth, and Ullarian felt proud of her at that moment.

“I think it started with a T,” he said, sounding aptly befuddled. “Or a U. But what kind of an idiot has a name that starts with a U, am I right?”

“My grandfather was named Umar,” said the guard in gold.

“He didn’t mean any disrespect,” said Sultana. “Forgetting one’s own name comes with forgetting morals and a misplaced sense of rights and wrongs. It’s very severe, which is why—”

“All right, all right,” said the guard in silver. “But before entering you have to answer his question.” The guard pointed towards his partner.

“What succeeds war but precedes peace?”

“That’s an unusual question to ask, because peace is neither the opposite of war, nor an absence, but a calm persevering of it,” said Ullarian. The guard in gold stood in silence for a full minute, before nodding at his partner. The crescent door shifted with a groaning noise first, and then a sharp slashing of the air.

Ullarian and Sultana walked inside the city of Messan.

***

Later, as they stood at the base of the Ladder, looking up at the pyramid which housed the Tapestry, Ullarian asked Sultana if she would consider living with him for the rest of their lives. He would make tea for her, in the morning and at night. She would knit him sweaters, and they would take care of the bees.

Sultana didn’t say anything, but took the first step on the Ladder. Ullarian followed her. Sixty steps later they arrived on a landing, which overlooked the great expanse of the Messan city and, in the distance, the small needle-like spire of the Astor lighthouse, and the blue beyond of the sea.

Two thousand steps remained, and only then would they reach the point where the Golden Elevator started. Reaching the Tapestry was a test of patience and endurance, and meant for the young. Ullarian and Sultana were the only Keepers in the world in the sixth decade of their lives.

Sultana lay down on the platform, her breath coming in shallow gasps. Ullarian’s heart was fluttering like a bee. He sat down beside Sultana, looking at the city.

“Is it worth it?” asked Ullarian. “Two thousand more steps, Sultana. Is it really worth losing our bodies in the process? The last time we came to the Tapestry together was two decades ago.”

“When all this is over, we will live together. But we need to do this.”

“I know better than to argue with you,” said Ullarian, with a smile on his face. “Rest for a while, we have a long way to go.”

“I feel—”

Sultana stopped, her next words dangling at the cusp of her tongue. Her lips were patchy, cobwebbed, and her skin was dry. She was moving her mouth and yet her eyes flitted around madly.

“Sultana.”

“I feel I need—”

She massaged her throat, and yet couldn’t tell what she felt, what she needed.

“My throat feels like it’s clotted with sand. Something…”

Ullarian felt what she felt, but he couldn’t mouth what he needed to make the feeling of dryness subside. The idea of cooling down his throat felt like a dark vapour, vanishing.

Ullarian looked up. Beyond the Astor lighthouse, the blueness was evaporating slowly.

“You stay here,” he said, in panic. “I’ll go up.”

“No… if it has started, we have to stop it together.”

Then, they both began their long ascent, without knowing why their throats felt parched, or the method for making the feeling go away.

***

The Tapestry was not one tapestry, but many tapestries, hanging low, their borders ornate, studded with jewels, sapphire, ruby, onyx, emerald, their dull beige fabric littered with jet black ant-like scrawls. To an untrained eye, those would look like haphazard letterings of a child.

But a Keeper could tell each stroke, each scrawl, each cursive letter, thin or bold, that mingled into other letters to form words on the Tapestry. The Tapestry nearest to Ullarian was filled with semaphore, trolley, underpants, ill, will, yowl, havoc, wanton, pulverise, caution, quixotic, ubiquitous, poison, gamble, elation. He looked up and saw ration, toil, kaftan, pashmina, evening, haphazard, drama, camphor, and to his utter relief, sky. Higher and higher up the tapestry went, until it touched nothingness. The top of the pyramid was gleaming like a jewel from the inside.

To Ullarian’s side stood Sultana, dazed out of her mind, breathing heavily. For many long minutes, they had been standing like this, looking at the sprawl of the Tapestries, their eyes eager to find the absence they knew not the meaning of.

Ullarian finally took a step, then three, then five, until he reached the center of the giant room. He felt the sharp fabric of two tapestries against his skin, as the words written on them danced in front of his eyes.

Then he saw it.

A child crawled on a tapestry, clutching its fabric with a practised grip, like he had done this a thousand times before. No more than eleven, he was doing the impossible — crawling across the fluttering surface of the Tapestry, a brush in his hand, unwriting and rewriting words. On the ground, a massive glass container was overflowing with blue ink, dripping on the shining marble floor.

After removing a word right in front of Ullarian, the child began a silent crawl down to the ink bottle. He saw what the child had just unmade. ‘W’ and ‘A’ were left, and the rest of the remaining letters of a once-five-letter-word looked like ink-ghosts.

“Wa.. te… —” Ullarian tried to mouth it, complete it, but it did not make any sense. This was different from merk-seal. The idea of the word was simple, just as Sultana had predicted, yet it was all-encompassing; life itself hinged upon it. There was no room for ambiguity here, and they couldn’t replace the word with hasty substitutes.

Yet, water was proving hard to erase.

“Who are you?” Ullarian asked the child. The child did not answer. Instead, he dipped his brush in the ink, and climbed back upwards, up and up and up, to write over what he had erased, doing some form of Keeper’s work, intent on replacing the vanished tapestry word with his own.

“Stop!” Ullarian screamed. The child paid him no heed. Ullarian dashed towards the tapestry, grabbed the fabric, his right palm over ‘ululate’, his left eclipsing the t of ‘turmoil’, and yanked it. The tapestry was heavier than the world, the weight of so much meaning upon its surface, but it relented, because Ullarian was a Keeper, and had provided meaning to more words than one Tapestry could handle.

“Ullarian, no!”

Sultana’s cry echoed across the pyramid and got lost in the folds of the tapestry as it came crashing down, its overstretched cloth smeared by the blue ink, which spread inexorably across its surface, drowning out hovel, yearning, tears, lark, ergo, quest, charm, pedal, sort, karma, mist, end, black.

***

On a —less — in Astor, — woke up to the sound of buzzing.

— walked around in his —, straining his —,, but he couldn’t place where the sound was coming from. —, who wore a sweater with the letter ‘U’ on it, tried to remember the —, the previous —, and all the —s that had preceded, the events as they had happened, but his mind drew a blank.

He walked towards the sound, his steps unhurried, because his mind didn’t know the meaning of hurry, or anxiousness, or eagerness. He walked towards the back — of his —, which was ever so slightly ajar. Dust motes hung in the air, streaming through the gap. He flicked them, and they shivered and then danced.

A smile came on his face, even though he didn’t know what it meant. He opened the — and went outside. A woman stood ten feet away, holding a —. Hundreds of dots swirled around her head, attracted towards the — the woman was holding.

The woman’s name existed at the far edges of his memory, ever threatening to slip into chasms where even memory couldn’t reach. He held on to the first letter of her name. It started with S. The rest of the pulling he can do. He knew.

She looked at him. He looked at her.

“Good morning,” she said. “This is an apiary. These are bees.”

He asked her about the —, and how the — had scribbled across the fluttering —, and what the absence of — meant, and about other absences, in as many words he could —.

“Words will come to you, slowly,” she said. “The folds of the Tapestry are being ironed, as we speak. Every stitch, every seam, back to the way it was.”

A smile flickered on his face. He knew ‘smile’ and what it meant. But he didn’t know himself, and she must have read the blank page that his face was, because she took his hands in hers, and said, “You are Ullarian. And I am —”

He completed her sentence, saying her name, the word tumbling out of his mouth like a —fall.

© 2023 by Amal Singh

3612 words

Author’s Note: I’ve always been fascinated by the nature of memory. One of the first short stories I remember reading which tackled memory was Neil Gaiman’s “The Man Who Forgot Ray Bradbury”, and ever since then I’ve wanted to do something like that in my own fiction. The first line of my story is something I wrote very casually on a google doc, one day, and realised that I had it, finally. The rest of the details, the strange world of Astor, revealed itself gradually.

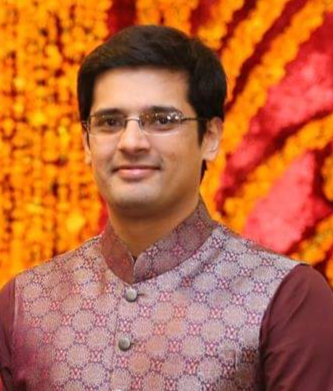

Amal Singh is an author and an editor from Mumbai, India. His short fiction has appeared in venues such as F&SF, Clarkesworld, Apex, Fantasy among others, and has been long-listed for the BSFA award. He also co-edits Tasavvur, a short fiction magazine dedicated to South Asian Speculative Fiction.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.