You feel an explosion and wake up face down on a rocky patch of dirt. A spurt of blood fills your mouth with iron and salt, and you push to your knees, gagging, but all that drools off of your lips is soil and leaves and a few bitter-tasting pine needles. You breathe and spit, but the blood taste is gone. It never was. You exhale relief as the panic fades with the dream.

You raise your face to a clear yellow sky and chilly air, the white sound of water rushing over you with a comfortable, misty breeze. It’s the smell of the park when the elk are bugling and camping means nights in flannel over canned spaghetti, and no problem with the cold because it makes the heat of the fire so incredibly perfect.

And you hear an enormous voice. “Is that a memory?”

You end your moment with the sky and lurch to your feet, backing away from the rocks and slick bracken along the river bank, which you realize is very close. And straddling the river with its hind-claws—its left fore-claw gripping the soil on the far bank and its right fore-claw stirring down in the white rush—is the bear.

“Hello,” he says through the wet of his muzzle.

He is huge. Impossibly. The river tumbles down a falls and through the bear’s legs and off into mist down the second falls, where the woods and the rocks and the world seem to end. The river is too wide for the rotted trunks to reach across where they’ve fallen, and yet the bear stands across. And you watch as his right fore-claw snaps up from the river, trailing silver droplets, and flicks the strong, twisting, desperate body of a fish into his jaws. He eats it whole.

“Don’t be a cliché,” he says, and you know he means the question you’d taken a breath to ask. You feel embarrassed, and then immature for the embarrassment, but you can’t help it. Bait or no, you take the challenge. And instead of “where am” or “how did,” you decide on “what the.”

“Are you really a bear?” you ask.

He takes another fish, this time lopping it in half with a bite and flinging it aside so that its back half flies into the woods streaming entrails and a rain of blood. “There are no bears here,” he says.

The river is crowded with fish. You can see them just below the surface where the rushing white foam occasionally separates to give clarity, all swimming against the current. Even as the bear says “here” a fish leaps out of the river, thrashing and aimless. The bear rakes it in mid-air and the fish lands near you in a skid of dirt, split by three gashes along its body.

You step close and see that it’s a big fish, and the mess of its organs is very still, and there is no gasping like you expect. Something is very wrong. You pinch the tail. It feels like suffocating in a hot adobe hospital from a throat closed by snake venom and being too young to go this way, mierda, too young. You let go of the fish and leap back. God damn. God damn, what is that? Who is that?

“That’s not a fish,” you say.

“There are no fish here,” he says with three fish squirming in his mouth. He grumbles pleasure around the tearing of their scales by his teeth.

You run. With the roar of the river at your back you dodge the rocks and fungus-ridden trunks that the erosion has brought down. You scramble over a big rock with its inch-thick moss and jump off to land in the shadow of the trees of the heavy green wood with your slippers thudding wet in a cluster of mushrooms. (You’re wearing pink slippers.) The low leaves are wet on your face as you push far away from the bear. (Slippers. Isn’t that strange?) Fish bones lie among the roots, their rot feeding the trees, which are old and soon to fall to add to the rot, the fungus and mushrooms the only brightness.

Eventually you overcome the panic and you start to think again. And you slow down. You stop. You think about the bear and the river and the fish and the falls while you pace tree to tree, while you watch that yellow sky and taste the air full of moldy years, and soon you turn around and follow the sound of the rushing water.

You find the bear straddling the river eating fish, snatching fish from deep in the stream, snatching fish from near the surface, swatting or biting the ones that leap. Two at a time. Four at a time. Some are small and bright and young. Some are old with milky eyes. The one from the bank is gone. In his belly, you know.

You’re afraid to ask. But you ask.

“Those,” you say of the fish being slaughtered, “are they people?”

“Sort of,” says the bear.

“Souls?” you ask.

“That’s closer.”

You try to remember the dream that woke you here. It was terrible, and more important than anything. And you can’t remember any real part of it. Just the feelings, and they’re fading.

“This is all you do?” you ask. “You eat them?”

“They’re delicious,” he says with a simple black madness in his eyes. “The fast ones are delicious. The slow are delicious. Big, small. I love the taste.”

“Are you Death?”

The enormous and magnificent bear, with his perfection of fur and hugeness of musk and multitude of teeth, who feeds from this river and all of its millions of fish as they thrash ceaseless against the current, the being and master of this place, he nods.

“But not God,” he adds.

“No,” you say. And he seems offended, though you’ve only agreed with him.

“Am I dead?”

“Absolutely.”

You sob. It’s what you expected to hear and still it hits you with horrible sharp stabs in your chest, and you bend with your hands on your knees and sob with a grief you don’t understand.

“There are no tears here,” says the bear.

But you’re crying. You kneel down by the water and look past the foam to the fish swimming with every bit of muscle in their bodies, some thumping against the river rocks, some dodging. Their wild silvery mass is in one place rhythmic, the long shapes in sinuous concert like a dance, and in another place chaotically brutal with each swimmer thrashing against the other. You want to jump in. You need to jump in. You need it more than you can stand.

You never see the bear’s claw. You only tip yourself forward to drop into the water and the claw swipes you, knocking every sense into blackness, and you land hard on the bank. And slowly, in the brown drooping ferns, you come back to yourself.

You force yourself to stand straight, hands atop your head to ease the ache in your chest, and you pace along the bank while the bear devours fish. The pacing helps you ignore the queasy sound of his meals and the need for the river and your rage at the bear. Pacing helps you think. And you know this is a habit you have, though there are no memories attached to it. No memories at all.

“How did I get here?”

The bear chuffs. “The cliché.”

“Whatever. Just answer.”

The bear yanks out a fish. “I yanked you out.” He crushes it so it bursts, and he licks the meat from his claw.

“But you didn’t eat me.”

Silence.

“Why didn’t you eat me?”

More silence. Even the river seems hushed.

“You don’t want to say,” you tell him. “Why not?”

The bear says nothing. He catches fish and eats them, but all the relish is gone, all the flair gone flat and mechanical, claw to mouth to water to mouth, until finally he nods and the moment passes. The river sound roars back to life. The bear knocks a huge fish high into the air and snaps it on the way down.

“I don’t want to tell you,” he admits. “But I will because you’re interesting. You jumped out.”

“Out of the water?”

“There’s no water h–”

“Just tell me!”

“No. I already said, I yanked you out of there.”

“If not there, then what–” And you realize it. “I jumped out of your mouth!”

The bear chuffs.

And you make a choice in that instant, all at once. You’re going back into that river. Fuck this bear. Fuck death. You’re going back. And you know he knows what you’re thinking and you don’t care because the need in you is big enough and mean enough to crush him alive.

“Not likely.”

“I jumped out of your mouth,” you declare to him. “I had my way. I’ll have it again.”

The bear swings his massive head toward the near bank and fixes you with eyes of emptiness, and he roars. The river roars. The rocks roar. The fever-bright mushrooms flare to mad color. The trees and the ferns, the soil under your feet, every molecule around you whips with the explosion of his voice, throws you down hard. You cover your ears and press your face to muck, the old leaves dancing to the vibration, but the roar grinds through you no matter how you brace. And all you can do is take it.

When he’s finished, you’re covered with bits of gnawed fish, you’ve learned you can feel pain in this place, and you have a plan.

You lie where you’ve fallen for a long time in the cold mud, watching him. You watch the bear massacre the fish like a two-year-old ravaging the boxes and wrapping paper on the floor of the living room, high on cake and ice cream and attention. The river mist is a sporadic touch on your cheeks. Your heart aches so sharply you wince.

When the bear knocks a leaping fish to the far bank and turns to devour it, you jump to your feet, dash to his rear, and leap from a rock headlong for the water. The hind leg this time, it kicks you so hard you come to your senses back in the trees, the river out of sight. You brush yourself off and limp back to the bank to sit, and wait, and try again.

You don’t count your tries. You can’t track the time. There’s no time here, he says needlessly. You only know that he swats you every time.

“What’s down there?” you ask of the edge where the river disappears.

The bear shrugs a shoulder.

“Do any of them go over?”

“A few,” he says.

“What about up there?” you ask of the cliff from which the river seems to originate, the fish fighting madly for that goal.

The bear shrugs both shoulders. “Fewer,” he says, spraying guts from his mouth.

“Do you know them, the ones you eat?”

“I know them all.”

“How many have there been?”

“There are no limits–“

“Fine, fine, just— You must like some more than others. Which are your favorites? And why?”

The river’s noise hushes. The bear says nothing as he catches fish and eats them, returning to the mechanical rhythm once more. Finally he nods and the moment passes. The river noise climbs back to its height.

“Jemet, no fear in her, none at all. Bad Foot for the very wild dreams. Wei Wei and Li Jing, brother and sister, nearly psychic. G!au, two lions killed with his bare hands, proudest one ever.” And on he goes. He likes to talk, to brag, even when you’re not listening.

You leap for the river and he smacks you back. You walk the woods and study. Most important, you ask him more whys.

What you learn:

A. You know you’re real. You remember your Descartes. Cogito ergo sum. So you want what you want. No room for doubt.

B. Everything comes here to die. The trees and other plants are wilted and brown, and you find an incredible number of bones. You dig. The bones go deep.

C. He’s a creature of habit.

The pain inside is a constant ache and you weep now at odd moments with a disturbing lack of control, but you know what you need. You’re ready. You position yourself at the best place on the bank where the leap to the river is brief and the water swirls in fast eddies. When you hit the water you’ll fight for the deep among the other fighters, so long as you can keep your mind. And that’s a thought that nags you: you don’t know what will happen when you re-enter. You don’t know how you’ll be.

“It’s odd that you think this will work,” says the bear.

“You have your nature, and I have mine. Don’t you want me to leave?”

“No,” says the bear.

And here’s the moment. Here it is, you know, and the stabs in your chest make you squeeze yourself to keep from screaming. “Why not?” you ask.

Silence. The river’s sound falls to a gurgle. The bear says nothing as he moves mechanically. Rhythmically. Predictably. You wait for his claw to shove a fish into his mouth, those eyes staring off, vacant, and you leap. You leap right under that massive arm, your face passing through the river water dripping from its fur, the stink of fish blood thick all around you. You know his speed from his countless smacks. You know the timing when he’s lost in thought. You’ve studied. And yet passing beneath jaws as long as cliffs and teeth as wide as crags and a head so large it blots the yellow sky, you feel those eyes come back to focus and that claw jerk to snap you up. Too soon. Too quick.

Too late. You hit the water in a shock of pain and cold as behind you the voice of Death admits, “Because you can’t be friends with food.”

You swim. You fight. You pull against the current with the other fish smacking against you. Death’s claws spear the water and you twist away. Down. Down. And down until the yellow light fades and the thumps of striving tails become distant. And you are simply you. Only you. Beating against the current.

You hear crying. You hear the babies calling for you. “Mommee! Mommeeee!”

You wake up with a start. A spurt of blood fills your mouth with iron and salt. You try to spit and something in your chest rips. You try to gasp and the pain rockets into your skull.

“Mommeeeee! Mommy help!”

Think. Oh, Jesus. Think. Focus. You force your eyes to make sense of the light and you realize right away that the car is tilted wrong and the windshield is shattered. Red darkness comes pushing at the edge of your vision, but you can count the lengths of iron rebar jutting from the back of the truck through your windshield and into your chest, three of them, low, center, and high, your ribs scraping when you lift your head to look. And you’re weeping, no breath to sob, and your hand is reaching for the glove compartment because you smell gasoline. And the babies are in the back.

“Mommy, I’m stuck. Mommy! Mommy please!”

You wrench open the glove compartment. Something rips where your heart should be, and you want so badly for the breath to scream. There isn’t any.

You die.

The claw grabs you, squeezing, as you fight against the current, and it snatches you upward and into a wash of old yellow light. The bear’s jaws come closing but you twist against the fucker and you’re free, falling. You hit the water, pulling hard.

“Again!” he calls as you go under.

This time you come back remembering–six days in a row on-call and now sweatpants and pink slippers on your day off, rear ended at the red light and the explosion of your car slammed against the work truck ahead–and your hand is already rummaging through the glove box when your eyes snap open. Your hand is wet and sticky with black ooze, and you know the colorblindness is a sign of head trauma, and the speed of the blood spurting from the wound above your breast means catastrophic damage to the subclavian artery, and your sticky hand closes on the multi-tool. You fling your arm and throw the multi-tool into the back where it lands in the middle, between Olive strapped in her car seat and Weaver struggling with the tangle of his seatbelt. Escape hammer and seatbelt cutter in one. You’ve taught him how to use it. Always teaching. Immune to the rolled eyes. Not a cool mom. But that’s fine now. That’s fine.

“CUT!” you scream with all the breath you have, and you die.

The bear claw pierces you this time, and it’s not the same as the hot animal pain of the rebar in your heart. It’s a slash of nothing. A tatter of you gone.

Instead of pulling away you twist into the claw, feeling it rip deeply. But you’re free.

“Three times!” calls the bear, delighted.

You’re turned in your seat, cold air seeping into your broken cavity, the horrific, greasy smell of fire signaling panic even as your thoughts twitch in jagged fits. The car is burning, and it’s over. You know it’s over. You have nothing left.

And all at once, it’s fine. Your boy. Beautiful boy. He’s free, and he has his sister free, and long arms are reaching through the shattered window and pulling them out, the multi-tool falling to the white litter of glass beside the cut, gray, frayed piece of seatbelt.

“I can’t get to her!” shouts a fish. “Leave her!” screams another. “Get out! It’s going up! Get out of there!” The claw ignores them and snatches you out.

It’s not hard to fight him anymore. You simply give everything you have. You twist and thrash, and this final time you land back on the bank. When you stand, you’re in your slippers.

“I nearly ate you,” he says, his tongue rolling fish meat behind his teeth.

“It’s what you do,” you say.

The bear chuffs. “Getting away is what you do. Four times. That’s impressive,” he says, and means it.

“Is that a record?”

“Not even close. But it’s still very impressive.” He splashes with both of his front claws and shoves a mass of writhing bodies into his mouth. The first bite makes a wet burst, loud even over the river. “What do you want to do now?” he asks.

You think about it, and point. “I may go up there,” you say of the cliff from which the river originates. “Or down there,” you say of the falls into which it disappears. “Or I may just ask you questions. Why do you care?” you ask him.

Silence. The river becomes hushed. The bear says nothing. He catches fish and eats them, but all the relish is gone, all the flair gone flat and mechanical, claw to mouth to water to mouth. You watch one writhe in his grip, fighting for life.

You leap from the bank and knock it loose.

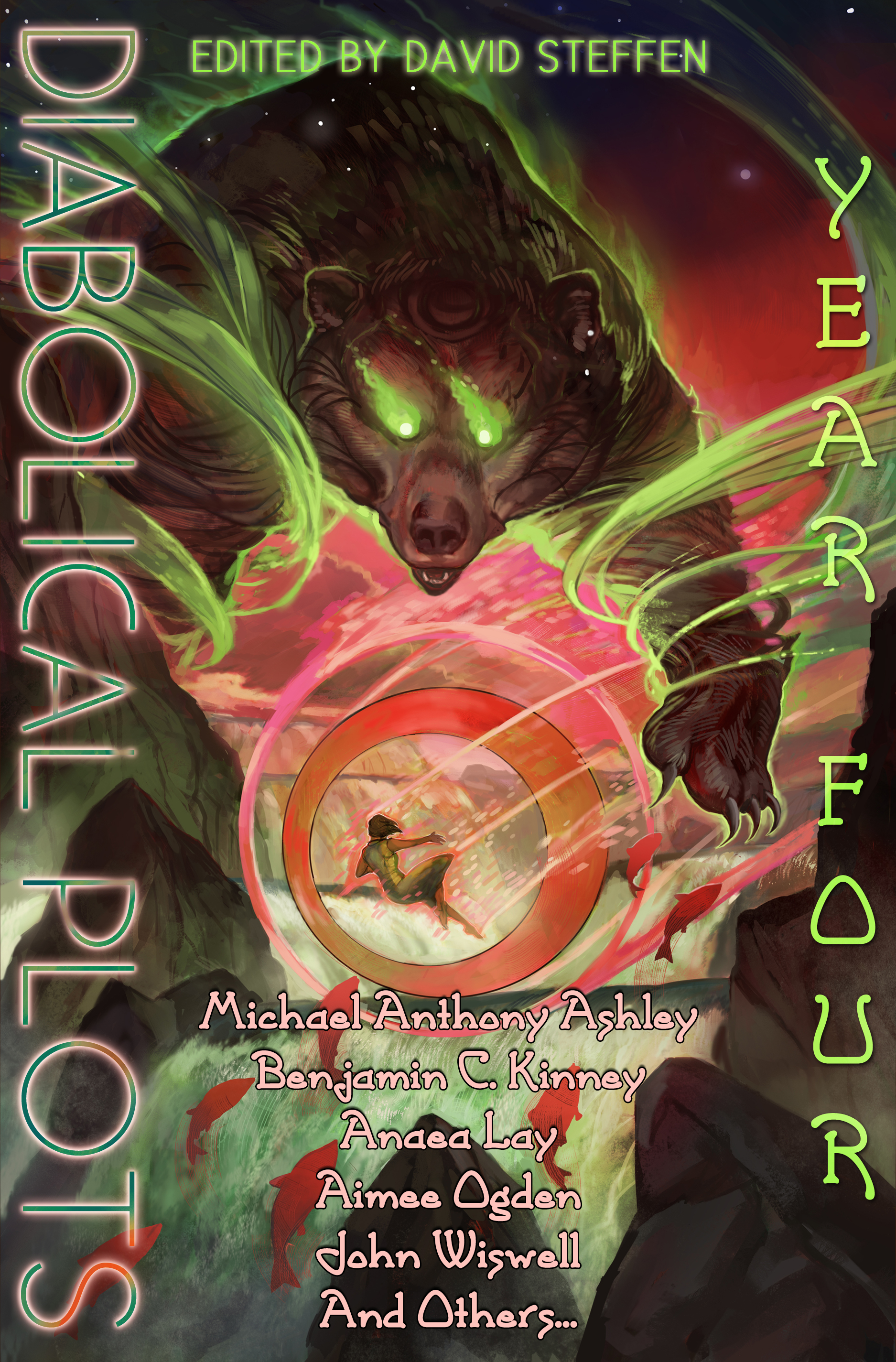

© 2018 by Michael Anthony Ashley

Author’s note: “The Fisher in the Yellow Afternoon” was a round 2 contest submission for WYRM’s Gauntlet 2016. The prompt was to write the story of a character who has recently died, telling what led to the disappearance and what may be coming next. The catch was that it must be written in second person POV. The Gauntleteers, as we were named, were given one week. Aside from proofing edits and a change to the last line, the story you see here is unchanged from the competition.

Michael Anthony Ashley is a 2004 graduate of the Odyssey Writing Workshop and a longsuffering ghostwriter of nonfiction. He has published short stories with Beneath Ceaseless Skies, flashquake, and the Czech publication Pevnost. In his daylight hours he works in public health, helping to broker the peace between bacteria and humankind.

Michael Anthony Ashley is a 2004 graduate of the Odyssey Writing Workshop and a longsuffering ghostwriter of nonfiction. He has published short stories with Beneath Ceaseless Skies, flashquake, and the Czech publication Pevnost. In his daylight hours he works in public health, helping to broker the peace between bacteria and humankind.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.

The Lego Ninjago movie is a computer animated children’s movie from Warner Bros, released in September 2017. It is in the loosely connected series of Lego movies that include The Lego Movie and The Lego Batman Movie. Similar to those movies, pretty much everything in the movie is made as though it were built out of Lego blocks, and though the movies generally don’t often acknowledge that they are actually toys, it occasionally does (usually for comic effect).

The Lego Ninjago movie is a computer animated children’s movie from Warner Bros, released in September 2017. It is in the loosely connected series of Lego movies that include The Lego Movie and The Lego Batman Movie. Similar to those movies, pretty much everything in the movie is made as though it were built out of Lego blocks, and though the movies generally don’t often acknowledge that they are actually toys, it occasionally does (usually for comic effect).

The Boss Baby is a 2017 computer animated comedy/action film produced by Dreamworks Animation, released in March 2017.

The Boss Baby is a 2017 computer animated comedy/action film produced by Dreamworks Animation, released in March 2017. Sleeping Beauties is a drama/fantasy/action novel written by Stephen King and Owen King published in September 2017 by Scribner.

Sleeping Beauties is a drama/fantasy/action novel written by Stephen King and Owen King published in September 2017 by Scribner.

Captain Underpants: The First Epic Movie is a computer animated film produced by DreamWorks Animation that was released in June 2017 in the US, based on the long-running book children’s book humor superhero series.

Captain Underpants: The First Epic Movie is a computer animated film produced by DreamWorks Animation that was released in June 2017 in the US, based on the long-running book children’s book humor superhero series.

Super Mario Odyssey is a new 3-D platform action game in the beloved and long-running Super Mario series of games, released by Nintendo for the Switch platform in October 2017.

Super Mario Odyssey is a new 3-D platform action game in the beloved and long-running Super Mario series of games, released by Nintendo for the Switch platform in October 2017.