This is important. When Margaret moved to the city, you see, the office she worked in was on the top floor, five stories up. The train took twenty-five minutes to travel between Bleek Street—where her office was—and Swallow Avenue—where she lived. She took a room in a basement, and that basement room was ten feet below the ground, and through the eighteen-inch windows at the top of the room, daylight filtered in. The reassuring whisper-hum of the underground trains tickled the soles of her feet every few minutes.

She’d kept hearing the city was growing. She figured, that’s where the jobs are—so she’d moved there. And yes, it was true, there were all kinds of jobs. You could be a copywriter, or a production assistant, or a construction worker, or pharmaceutical saleswoman, or a waitress at a fancy restaurant, or a waitress at a cheap diner, or a mail woman, or a graphic designer, or a barista, or a zookeeper, or a city planner, or an executive assistant, or a plumber, or an engineer, or a nail technician, or a food truck driver. That was part of the excitement: the possibility. The city was big enough for anything, bold enough to swallow anyone and spit back out a well-adapted spider monkey to climb the skyscrapers. Folks moved with an animal grace through the streets, stepping lithe around the potholes and trash, extracting quarters from their pockets without fumbling when the homeless people jangled their coffee cups.

She’d liked the office with the view—the bumpy horizon of skyscrapers, historic and glassy-obsidian-new; the obstructed but beautiful sky; the surrealist haze that lingered and that was equal parts factory, cigarette, and vape shop. She’d taken the job at the office with the view without really knowing what the job was about. It had something to do with spreadsheets and calendars. It didn’t much matter what she did.

“Every morning I walk out of the train platform, and I look straight up and can hardly take my eyes off the ceiling of the world till I walk inside the building,” Margaret told her mother.

The five-story building was a walkup, and Margaret didn’t mind. She hummed in the stairwell, failing to count her steps.

This is important. She was distracted and dying to be enchanted. So it took her a while to notice.

*

One evening Margaret came home and descended the stairs to her basement alcove. Her legs were powerful now, after a few weeks of climbing those five stories, the stairs to the subways, this path to her bed.

At the bottom, she put her foot down, expecting the tile floor. Instead her pump found the slick edge of another worn stair. She stumbled, barely caught herself on the railing in time to avoid a face plant.

Strange, she thought.

“These godforsaken shoes,” she said to her mother on the phone.

The light falling from the high, squat windows seemed a little dimmer.

*

She noticed, eventually, that where once she’d only been able to hum her favorite Johnny Cash song’s chorus three times while claiming the stairs at work, she now could almost finish a fourth repetition.

Outside the gilt-edged windows in the historic office building, the construction workers and cheap diner waitresses and engineers looked a little smaller.

“Nothing is ever finished, is it?” said her boss, dropping a stack of papers on Margaret’s desk.

The factory-cigarette-vape shop haze shimmered outside the windows.

This is important—or rather, it’s not. In the evenings, when she got home and eased her heels carefully over the unexpected last step into the basement, Margaret could not have told you what she’d done all day.

*

She noticed the clock more now. How the quiet, stuffy minutes in the train seemed to stretch out between the stops, unfurling, leisurely, absent-minded. When she looked up from the sidewalk, the edges of buildings hemmed the once-unbounded ceiling of the world, the perspective making them narrow dramatically toward the sun.

Mail began coming in bins, directed to the “6th floor.”

“Should we change our address on the website?” asked Margaret, who, she remembered in this moment, was in charge of such things. “Facebook?”

“What do you mean?” asked her boss. He pointed to the website open on her computer—6713 Bleek Street, 6th floor. “It’s always been the sixth floor.”

Margaret read every address on every piece of mail backward, from the bottom line up, to be extra sure that her brain wasn’t automatically filling in a number. Still, the number 6 made her bones feel brittle, fragile. She was glad she took the 8 train home.

*

In her basement room, which she swore now sat two steps lower into the ground, she heard the train passing the wall directly next to her bed. Strange. It didn’t seem like sinking two steps should bring her bedroom latitudinal with the train.

But, you see, she liked how the rumble had moved from under her feet to level with her chest as she faced the wall at night. It began to feel like the gentle but deep vibrations of a snoring lover, perched next to her under the sheets.

*

On a Thursday night, she went out. The bar she ended up at was three blocks from her heightening office, a puzzling intentional mix of hole-in-the-wall-dive and classily dim-lit, marble surfaces.

She sat alone at the bar stirring a gin and tonic until some man decided she looked lonely enough. It was an accurate observation. He settled into the stool on her immediate left.

“Where are you from?”

It was a question no one had ever asked in her hometown.

She gave its name; added, sheepishly, as one was supposed to do if they hadn’t been raised in the city: “It’s just this little town. I moved to the city a few months ago.”

“Oh? What for?” he said, rolling the tiny straw from his drink between his thumb and forefinger. It was not a frenetic motion—it was something unhurried.

This was where she was supposed to say what her job was, or admit she had attended an expensive university here. Even though she knew this, Margaret found that the question clotted in her ears, plugged her throat.

“I work on Bleek Street,” she said. She was changing the subject; the man did not know this.

“Oh—I work two blocks over.” He held her eyes. Margaret noticed, startled, that he’d looked her straight in the eye for their whole conversation.

He smiled, a toothy, guileless, out-of-place smile. As if the proximity of office spaces were a serendipitous coincidence, not the rational result of two people wanting to drink after work and not wanting to take a train across the ever-widening midtown expanse just for that. Margaret stared at him, the pads of her fingers dripping condensation on her glass. She felt as if she were on the train again. Trapped in the split second of darkness and encroaching bodies in which she feared, irrationally, that she would never get off, that this was eternity. That the moment would never end, or if it did, that it would never leave her.

“Have you noticed the buildings?”

“The buildings,” he repeated.

“They’re… growing.”

“Growing?” He leaned closer, placing his palm on the stool that separated them to steady himself.

Strange: a stool, separating them.

“And sinking,” Margaret continued, unable to stop herself. “And moving further apart. The train takes longer. The underground sank deeper.”

He tilted his head.

“Buildings,” he said again. “Growing.”

*

In the coming months, her office changed its address from the 6th floor to the 7th, then the 8th, 9th, 10th. It remained a walk-up.

Four more stops appeared on the train between Bleek Street and Swallow Avenue. The stairs leading down to Margaret’s basement room added a platform and doubled back in a second flight, and she had to crouch while descending in darkness. No more light reached her from the small windows.

She didn’t see the man from the bar again. He’d entered his number into her phone and texted himself from it—a process that made her wrinkle her nose, but remain silent. But when she looked in her messages later, the conversation had disappeared. All her conversations had disappeared.

Above her, the trains whispered and hummed. The vibrations fell on her as gossamer-light and chilling as spiderwebs.

*

When she called her mother, the line rang indefinitely. She didn’t pick up; no robotic voicemail came to save her from the anxiety-adrenaline of waiting for the next ring, the silent begging for a dial tone.

Margaret waited for almost an hour, letting each ring saw on her nerves as if a nail file on a piece of string.

“I miss you,” she said between tones.

Ring.

“I met a guy,” she tried. It felt hollow and she was glad, for a moment, that there was nobody on the line. She shook her head, hung up, and redialed: a clean slate.

Ring.

“I read a poem once—”

Ring.

“—something about, you know, city as lover.”

Ring.

“Like how people are home.”

Ring.

“Um, okay, that’s not important.”

Ring.

“This is important.”

Ring.

“Do you remember when I was little?”

Ring.

“And I counted the cracks in the ceiling—”

Ring.

“Every night before I slept.”

Ring.

“There were seventy-seven.”

Ring.

“I can’t find cracks to count anymore.”

After that, the phone stopped ringing. Only the laden, breathing silence of a receiver, depositing soundbytes into some irretrievable void. Maybe at least the phone company was recording. It comforted her to think that somewhere her voice was frozen, trembling over the syllables in “seventy-seven.” Finally a number that couldn’t change.

*

A growing city requires all kinds, devours all kinds. Margaret passed the storefronts, caught the job classifieds in her periphery as she handed the morning paper to her boss. You could be an instigator, or a message, or a cookie tin containing only buttons, or a nosejob critic, or a law, or a grocery store mapmaker, or an Internet hoax, or a governess, or a pushpin collector, or a pocket square, or a bottle, or a ringbearer, or a liar, or a mathematician, or a lying mathematician, or a butterfly effect.

That was part of the excitement: the possibility. The city was big enough for anything, bold enough to swallow anyone. Something about a primate with a prehensile tail. And you see, these days, you really needed to climb, and you really needed that extra limb to hold on with. There was nothing to do but climb. There was nothing to do but be swallowed.

Margaret did something with spreadsheets and calendars. It didn’t much matter what she did.

*

On a Monday morning, six months after Margaret moved to the city, she stepped onto the sidewalk after a three-hour train ride.

She looked up at the ceiling of the world. She hadn’t been able to sigh about it to her mother for six weeks. Above her, a tiny misshapen circle of sky and an edge of blinding sun peeked from the encroaching gargantuan skyscrapers. The sky was more brick than blue now.

Margaret opened the door in her office building. She took a deep breath.

She began the climb. She did not hum, because she knew if she did, her voice would give out on the way up. She failed to count her steps.

She was distracted and enchanted to be dying.

This is important.

© 2019 by Nicole Crucial

Author’s Note: I was living in New York City for a summer internship. Unsurprisingly, I felt like a very small and young and alone person in a very big city. Unlike other places I’d lived, New York only seemed to get bigger with time—not smaller—and I thought, what if that was literal? This piece was a way for me to work out my loneliness and frustration, the disappointment with myself and with the environment I was in. I’ve since gone happily back to living in and writing zany, semi-magical fiction about the South.

Nikki Kroushl (writing as Nicole Crucial) is finishing up her senior year as a student of various dark arts (one of them creative writing) at the University of North Carolina Wilmington. She writes fabulist fiction and self-indulgent personal essays. She is far too enthusiastic about planners, punctuation, pasta, caffeine, and Instagramming her cat. Read more of Nikki’s work at nicolecrucial.com.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.

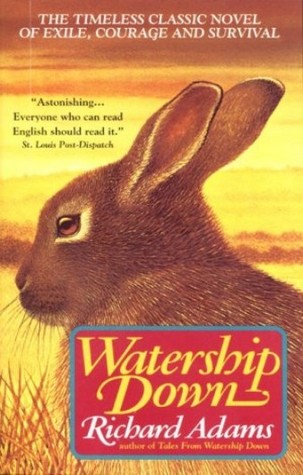

Watership Down is a survival adventure book written by Richard Adams published in 1972 that might arguably be classified as fantasy as well, which was adapted into a well-known children’s movie in 1978. It follows a group of young bachelor rabbits who run away from their warren when one of them has a premonition of coming disaster. The book follows them as they try to find a suitable location for a new warren and try to settle back down.

Watership Down is a survival adventure book written by Richard Adams published in 1972 that might arguably be classified as fantasy as well, which was adapted into a well-known children’s movie in 1978. It follows a group of young bachelor rabbits who run away from their warren when one of them has a premonition of coming disaster. The book follows them as they try to find a suitable location for a new warren and try to settle back down.