written by A. Nonny Sourit

editor’s note: this is a nonfiction article by the author describing their experience through a speculative fiction perspective. Adding this note because have received a couple communications that seem to think this is one of our fiction offerings.

Let me tell you of my trip through the portal, and what I found there: a world existing alongside to our own that is strange and different for the many of us who haven’t visited before. There was nothing that could be called a magical portal, in the usual sense. No passing through an impossible threshold like a mirror or the back of a wardrobe, but all the more strange to find what feels like a special pocket universe with no fantastical explanation.

This portal is merely a door. A door to an art studio. Dozens pass through every week, and think nothing of it. People who don’t pass through the portal may be discomfited to even discuss the world on the other side and speak poorly of those within.

To give you a little context to orient yourself, the particular variety of pocket universe I am referring to is often called a “figure drawing workshop” or a “life drawing workshop”. Figure drawing, or life drawing, is the practice of using a live in-person human model as the subject of visual art, done with the artist’s preferred materials: pencils, charcoal, watercolor, paint. While there are some figure workshops that have clothed subjects, generally the model is posing nude. While there are certainly many instructed figure modeling courses at art schools or through community education, my experience has been with art co-ops where there is a weekly figure model workshop run by a coordinator who arrange the models. All of the artists chip in a smallish amount of money (maybe $5-$10), most of which goes to pay the figure model.

I didn’t go to art school. I have never taken even community ed art classes, and I only started visiting figure model workshops as a (very amateur) artist recently. For a long time I have had artist friends and I would see nude sketches lying around and I’d ask them questions, curious about what it was like. A few years ago, I realized that I had been sort of lowkey fascinated with figure modeling for much of my life. It’s such a common nightmare for people to have to go to school and realize they forgot to put any clothes on. How brave a person must be to volunteer to do that and have a group of strangers stare at you naked for hours, I thought! I could never!

Figure modeling is a glimpse at a fantastical culture where the taboo of nudity is diminished and shifted. Usually the model will change into a robe in a private area before disrobing on the platform. When the model is taking a periodic break from posing they are expected to wear a robe. And new taboos are in place for the safety and comfort of the model. It is forbidden to touch the model while the model is nude, including things that might be appropriate in other scenarios like a handshake. To approach the model at all, you must first get the model’s spoken permission. Nudity there in front of a crowd of strangers, is not expected to embarrass or outrage or arouse as it is elsewhere.

Figure modeling is a human on display in an alien zoo. Okay, that’s not quite right. You are there for observation, but not exactly for entertainment. Of course it’s a bit different where the observers are all the same species as the observed. But in a way that makes it all the more speculative as we as adults generally know what a human being looks like.

Figure modeling is a mad scientist’s lab, though that’s not right either. Some of the artists there are professionals who have honed their skills for decades and just need a subject to perform their work which will vary from artist to artist. Though others may have never done any art before.

Figure modeling is a show. If a figure model doesn’t arrive or cancels at the last minute, one of the artists may become the model because the show must go on.

Figure modeling is time dilation. Outside the portal, we are expected to rush rush rush our lives away, to burn the candle at both ends, to hustle and bustle, always multitasking, and if you’re a parent not only doing this for yourself but for each of your kids trying to make sure they make it to sports practice and get good grades and stay in touch with family and going to social events. Most of us very rarely get much chance to sit still unless we’re so bone-tired we have no choice. But, when you’re a figure model, stillness is the job. If your brain decides to make a grocery list or something while you’re still, then more power to it, but I found it very enjoyable to just… think, in relative quiet, with nobody expecting me to talk, and nobody expecting me to hustle and bustle, and just let my thoughts randomly flow. And, okay, full disclosure, some of the thoughts were along the lines of “ow my butt hurts” and “can I shift my flex my foot without shifting it so it doesn’t fall asleep” and “this pose was a mistake”. A significant portion of the rest of my thoughts were examining the weird optical distortions you experience if you stare in the same spot without moving your head for more than a minute or two. And a part of my thoughts were thinking of writing this essay, and what the hell I would do with an essay about speculative fiction tropes and figure modeling and why would I even write this.

Figure modeling is time travel. Humans were making art before humans invented written language, and nude human figures have been a common subject since prehistory. The act of making art has changed drastically as technology shapes what kinds of tools, what kinds of pigments and materials are available. But the human body itself has changed much less–certainly some differences like hairstyles and the prevalence of body modifications like circumcision and the types of body shapes that are more favored by artists in different time periods, but when the main subject is nude, there are much less variations than clothed subjects where the clothing fashions change drastically between times, locations, and financial classes. The historical chain of nude art thins out in some cultures in some times when nudity is associated with immorality, but even so that chain never breaks and I guarantee that whatever future we end up in, we will end up with some kind of nude art and thus nude models in some form. Maybe the nude model is a simulation on the Holodeck, or maybe it’s an interplanetary art workshop where humans and other spacefaring species can pose for each other (with safeguards against diplomatic misunderstandings of course)

Figure modeling is a world where the playing field is leveled, at least theoretically. On the other side of the portal, everyone is welcomed as a model. When people think of modeling as a job, most people are thinking of a specific type of modeling, like modeling for magazine advertisements. Typical magazine ad models are a very narrow subset of humanity that fits a beauty standard that the majority of people don’t fit into. But figure modeling is very different in that respect–a skilled artist should be able to draw humanity in all its variations, and they learn and maintain that skill by working with figure models of humanity in all its variations.

In practice, I’ve found that the demographic spread of figure models is not very representative of humanity (slender Caucasian women being the majority , in my experience). There are probably multiple reasons for this. The most straightforward that some workshops may have an overt demographic preference, like asking for more women than men. But much of what decides who will be a model is based on who would choose to be. In my experience, most figure models were artists first. But that may introduce a bias: are art students the exact same demographic mix as the general population? In addition, figure modeling could be much more negative experience for someone who feels ashamed of their body after a lifetime of being told that their body is not the right shape or their skin is not the right color, and so this is something that might be much less likely to be considered for people who feel they don’t meet society’s unreasonable standards. I wish it weren’t so; I would love to see the population of figure models match the general population much more closely.

Figure modeling is Flatland. You are a collection of polygons and spline curves, not much different from a bowl of fruit or some other still life while you are on that pedestal. While you are on that pedestal, you are not a sex object; you are an object of art for the time you are there and when you’re done you walk through the portal and back into the everyday world. Maybe it’s not body positivity, but body neutrality, acceptance that bodies are bodies and we all have one and whether a body is beautiful is the wrong question, because all of our bodies have life and life is beautiful.

As I thought about figure modeling, I knew I could never. And then I started asking myself WHY I could never. I started to read about firsthand experiences of modeling and found that I was very interested in all of it, even in the boredom and tedium and ache of a poorly chosen pose, because the sheer mundanity of such a fantastical thing was so incongruous. The only reason I could never is because I told myself I could never. And, in true science fiction fashion, this led to the grand WHAT IF. WHAT IF I didn’t tell myself I could never. WHAT IF I decided I wanted to do a thing and then… WHAT IF I just did the thing.

I talked to my partner about it. I talked to the people who run workshops. I talked to other models. All of those things were very difficult because, as I have mentioned, I could never. But then I did anyway. And in the end, my first time as a figure model was much less scary than trying to start the conversations about it. On the platform, I was not scared. I felt no embarrassment. It felt very ordinary at the time, which in retrospect feels rather extraordinary. Most importantly, even when I am absolutely certain that I could never, I now know I could be wrong about such things.

If you’re reading this, and any of this sounds intriguing to you, I encourage you to give it a try! It’s been a fun and strange experience. Read firsthand accounts about it. Talk to artists and models and the people who run workshops. If you find the idea interesting, but you know that you could never, think on it some more. If even one person reads this and decides to try it, I would consider it well worth my time.

Even if this all sounds terrible, if there is something else that you’d love to do but could never, please don’t give up on it.

Maybe you could never, or maybe you could.

Now, if you’ll excuse me, I have a portal to catch.

ADDENDUM NOTES FROM THE AUTHOR:

In response to questions, and also realizing to some things that occurred to me after writing:

This was written from a perspective of someone living in the USA. I think the situation is pretty similar in Canada and the UK and western Europe in general, but I do not know in what countries this might be normal, and in what countries it might be frowned-upon or not permitted at all. I have not done the research to try to determine this.

You may have heard the term “Life Modeling” rather than “Figure Modeling”. The terms seem to be synonymous. I tend to use the term “Figure Modeling” more because “Life Modeling” has at least one other meaning: when some people talk about “Life Modeling” they are talking about more like a “life coaching” kind of thing, about examining all the parts of your life and how to live your authentic life, or something like that. I don’t know much about it, but obviously it is not the same thing (although figure modeling could be an expression of your authentic life!).

Workshops are different than classes, though they both use figure models. Workshops are more often outside office hours so if you have an office hours kind of dayjob they’re easier to work around, the people attending them are more varied in age, there is typically no instruction and walk-ins are usually allowed, and the working relationship might be less formal and structured, though the work itself is of course similar–except that in a structured school class the model might be asked to pose in particular ways for instruction, while in a workshop the model typically picks their own poses.

If you decide you would be interested in trying life modeling, here are some suggestions for how to get started (again this is USA based, may vary by local):

- Find a figure model workshop. If you live in the USA or Canada, check out Life Model Book’s state and province directory to try to find some workshops near you. If you live in a large metro area, there are probably many in your area, but smaller communities might have them too. You can check out art schools as well.

- Attend a workshop as an artist if you can. This is an advantage of co-op style workshops over schools, because you can often walk-in without even registering and just attend one session for a small amount of cash (much of which will go to pay the model). You don’t need to have ever drawn before–just bring pencils and paper and try it out, see how it feels from the artist’s chair.

- Talk to the people who coordinate the models and ask how they find their models. There may be an audition, or they might ask questions, might have an application to fill out, it varies.

A. Nonny Sourit writes technical things and also writes non-technical things, and would like to encourage you to stop standing in your own way.

Even before

Even before

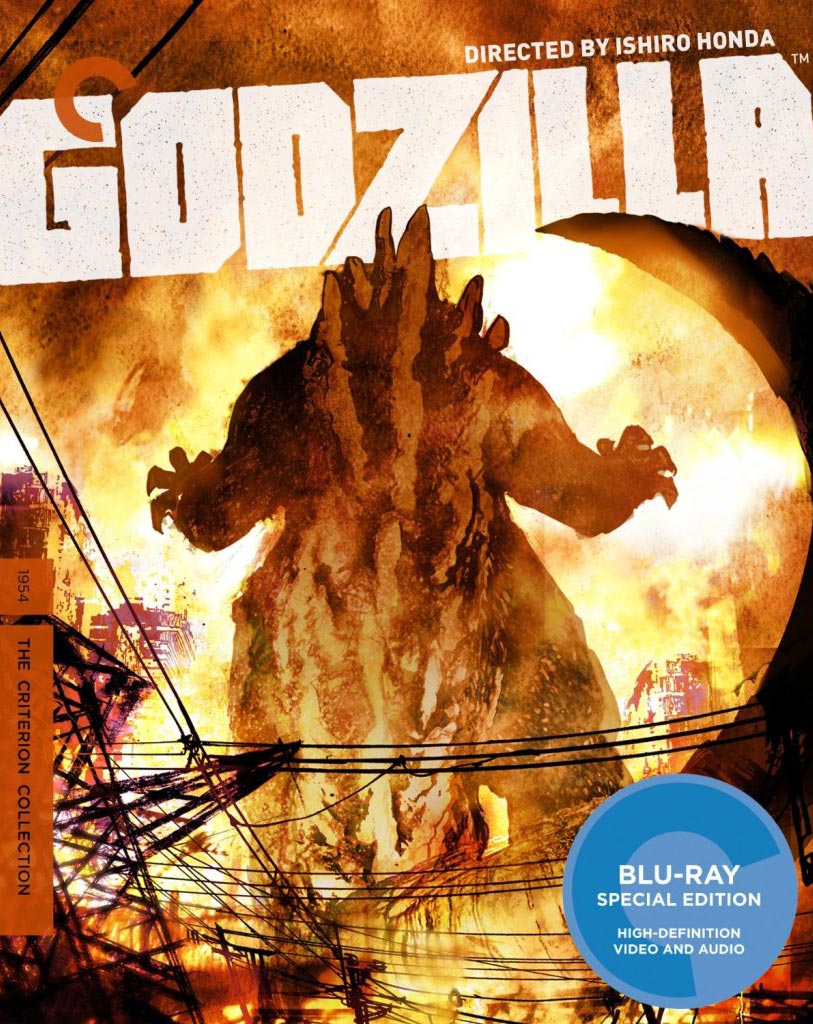

Godzilla (1954)

Godzilla (1954).jpg) The Bay (2012)

The Bay (2012) C.H.U.D. (1984)

C.H.U.D. (1984) The Day After Tomorrow (2004)

The Day After Tomorrow (2004)