written by David Steffen

We all know how the story of Pinocchio goes. Like most people, I watched Disney’s version of Pinocchio when I was a kid, and when I later learned that it was based on an older story (as most of Disney’s movies, especially their older ones, are) I assumed that Disney made some adaptations to make it into a modern children’s film–modernizing the language, trimming meandering plotlines. I knew that Disney had made drastic changes to the endings of the stories based on Hans Christian Anderson fairy tales because otherwise there’s just no way you could market them to a modern kid’s audience. But I had never heard anyone talk about how faithful their adaptation of C. Collodi’s Adventures of Pinocchio was.

I was working on a story loosely inspired by Pinocchio, and so to understand my source material as completely as possible, I wanted to read the original for a basis of comparison. I was quite surprised by what I found there. In particular, the character that Disney based their Blue Fairy character on.

I’ll give some general thoughts about the story first, and then will talk about the fairy in the section titled “The Original Blue Fairy is a Cruel Monster”. I’m not going to bother avoiding spoilers because the movie most people are familiar with is 73 years old, and the original book is 130 years old.

The Adventures of Pinocchio

There are a lot of details that might surprise someone who guesses that the Disney version is a faithful adaptation, including:

1. The Fairy does not make Pinocchio alive

He just is alive for no reason, speaking even before he has been fully carved from a block of wood.

2. The Talking Cricket (the inspiration for Jiminy Cricket) is killed by Pinocchio in the very scene in which he appears:

“Let me tell you, for your own good, Pinocchio,” said the Talking Cricket in his calm voice, “that those who follow that trade always end up in the hospital or in prison.”

“Careful, ugly Cricket! If you make me angry, you’ll be sorry!”

“Poor Pinocchio, I am sorry for you.”

“Why?”

“Because you are a Marionette and, what is much worse, you have a wooden head.”

At these last words, Pinocchio jumped up in a fury, took a hammer from the bench, and threw it with all his strength at the Talking Cricket.

Perhaps he did not think he would strike it. But, sad to relate, my dear children, he did hit the Cricket, straight on its head.

With a last weak “cri-cri-cri” the poor Cricket fell from the wall, dead!

I found this darkly hilarious, more so for the complete unexpectedness of it.

3. In the absence of the Talking Cricket, many other random bystanders serve the role of being Pinocchio’s moral compass.

This includes the Fairy herself, a Blackbird, the Ghost of the Talking Cricket, a Parrot, a Pigeon, a Donkey, and somehow the Talking Cricket again (having reappeared alive). It’s clearly a story to teach morals and really bludgeons you over the head with the format at every opportunity.

4. Geppetto has quite a temper (at the beginning of the story)

I normally think of Geppetto as a kind, sweet, old man, perhaps out of his area of expertise in parenting but an entirely benevolent character. In the original, though, he has a vicious temper and threatens to thrash Pinocchio at the slightest provocation at times.

5. Pinocchio is a mean-spirited beast(at the beginning of the story)

In the Disney movie Pinocchio is naive and easily tempted, but is generally a good person who is just misguided. The Pinocchio in the book is a mean-spirited creature who does mean things out of spite and for entertainment only

6. The escape from the belly of the Shark is super easy

Instead of Monstro the whale, the original story has a giant Shark that swallows Geppetto. When Pinocchio gets swallowed too, he finds his father where he’s been eating raw fish for two years in the belly, living in candlelight from candles salvaged from a swallowed shipwreck. Yes, TWO YEARS of eating raw fish. When Pinocchio gets there, they decide to find a way out. Apparently the giant Shark has asthma and so must breathe with its mouth open while it sleeps. Pinocchio and Geppetto literally just walk out of its open mouth and meet no resistance from the sleeping monster–there is no fire to make it sneeze as in the movie. Which really leads one to wonder–why didn’t Geppetto just walk out on his own sometime in the last two years?

7. The Fairy is very different (see the next section)

The Original Blue Fairy is a Cruel Monster

Now on to the really fun part–the reveal of what a psychotic, manipulative, pathological liar the Blue Fairy’s original incarnation was.

In the Disney movie, the Blue Fairy is about as benevolent of a character as you’re likely to find. She is basically an incarnation of kindness and love. She is the one that makes both the launching of the plot and the final climax possible. At the beginning, the lonely carpenter Geppetto wishes upon a star that his newly made marionette could become a real boy. While he sleeps the Blue Fairy visits the workshop and grants this wish, after a fashion. He has the spark of life, can act and think for himself, but he is still a wooden marionette as well. She tells him that if he can be a good boy and can listen to his conscience, then she will really make him a real boy. She sees him again later after he’s done some things wrong and gotten himself trapped in a seemingly hopeless situation, and she lets him go free with a warning that she won’t bail him out again. At the end of the movie, after Pinocchio has sacrificed himself selflessly to save his father’s life on several occasions and has learned virtue and truth and all that jazz, the Blue Fairy shows up again and makes good on her promise and makes him into a real boy. Hooray! The End.

In the book, the fairy is known as the Girl with Azure Hair, or the Maiden with Azure Hair, or in a couple scenes the Goat with Azure Hair, or sometimes just the Fairy. At the best of times, the most positive thing I can say about her is that she can occasionally act without malevolence. At the worst of times, she is a cruel, spiteful, monster who has all of the faults that she blames Pinocchio for having and others besides.

Pinocchio first meets her when he is running away from two con-men in the guise of Assassins who want to take the gold coins that Pinocchio has in his posession. Fleeing from the Assassins in the woods he comes across a cottage. He bangs on the door until the Girl with Azure Hair (at this point quite a young girl) answers at the window and this exchange occurs:

“No one lives in this house. Everyone is dead.”

“Won’t you, at least, open the door for me?” cried Pinocchio in a beseeching voice.

“I also am dead.”

“Dead? What are you doing at the window, then?”

“I am waiting for the coffin to take me away.”

And then she shuts the window on him. Because she won’t let him in the house, the Assassins catch him, beat him, try to stab him, and hang him by the neck because Pinocchio is holding the gold coins under his tongue and they can’t pry his mouth open. They get bored waiting for him to suffocate several hours later and promise to come back the next day to collect the coins from his dead body. The Fairy eventual wanders out of the house, has him cut down from the rope, and he is eternally grateful to her for saving his life even though she was the one who refused to help him when he was in trouble in the first place. He never questions why she claimed she was dead, and she never offers an explanation. I’m really not sure where Collodi was going with that brief conversation–is she supposed to be suicidal? Is it just supposed to be some amusing nonsense in place for no reason and he assumed children would laugh and not try to figure out the meaning? Is there some kind of meaning that is just eluding me because of the difference in time period and culture from where I’m reading it? I really don’t know. But this is not where it ends.

They decide after this exchange that they shall be brother and sister, and so they play childhood games with each other and have fun for a time. This is about the most positive Pinocchio’s relationship with the Fairy gets. The Fairy sends for Geppetto to come live with her and Pinocchio in the Fairy’s house, but Pinocchio is so overjoyed at this happiness that he asks to run to his hometown to find his father and tell him the good news himself. The Fairy agrees, with a warning that he has to behave. And of course, Pinocchio doesn’t behave, gets distracted, ends up having all of his gold coins stolen by the con-men who had earlier tried to murder him and in the backwards Town of the Simple Simons ends up getting thrown in jail for several months, more adventures ensue, and eventually he makes his way back to the Fairy’s house after much times has passed.

The little house was no longer there. In its place lay a small marble slab, which bore this sad inscription:

HERE LIES

THE LOVELY FAIRY WITH AZURE HAIR

WHO DIED OF GRIEF

WHEN ABANDONED BY

HER LITTLE BROTHER PINOCCHIO

So, as far as we know at this point, the Fairy is well and truly dead, and so Pinocchio is very, very sad about the death of his sister and guilty about his role in her death. I would’ve thought that his grief would be dampened at least a little bit by the fact that she was so spiteful as to have apparently commissioned a stonecutter to craft such a spiteful accusatory epitaph for her tombstone.

But then, after her second claim of death (don’t forget the first one made on their first meeting) Pinocchio happens across her again in his ramblings. Pinocchio is at a place with very hard workers and is begging for food from them, but refuses to work for the food. Finally a woman comes along and she gives him water freely and offers him food if he will carry her water jugs. He does agree for the promise of a feast, and then he realizes its the Fairy all grown up (I think this may be because he is an unaging marionette and she is just growing up at a normal pace, though I had at first thought that this is just another piece of dream logic). Since she’s older than him now, she takes the role of mother figure to him (which adds a bit of a weird psychological component in a single character sister-turned-mother). This exchange occurs:

“Tell me, little Mother, it isn’t true that you are dead, is it?”

“It doesn’t seem so,” answered the Fairy, smiling.

“If you only knew how I suffered and how I wept when I read ‘Here lies,'”

“I know it, and for that I have forgiven you. The depth of your sorrow made me see that you have a kind heart. There is always hope for boys with hearts such as yours, though they may often be very mischievous. This is the reason why I have come so far to look for you. From now on, I’ll be your own little mother.”

“Oh! How lovely!” cried Pinocchio, jumping with joy.

“You will obey me always and do as I wish?”

“Gladly, very gladly, more than gladly!”

She merely seems amused when he points out that she’s still alive after that accusatory epitaph. She deigns to forgive him, but makes no mention of needing forgiveness herself for inflicting such grief upon the puppet-boy, and in such a spiteful way. She not only moved out of the house she’d been living in, after all, but had it torn to the ground, laid a marble tombstone (which couldn’t have been cheap) and paid to have a spiteful accusatory epitaph carved into it. When she decides to teach a lesson she goes all out!

She claims to have searched for him but as far as I could tell he just happened to find her, not the other way around.

And his promise to obey here and do as she wishes was just chilling to me considering what she’s shown herself capable of. She promises that he will become a real boy if he proves he deserves it (note that she doesn’t say she will do it for him, only that it will happen).

She even picks a day for it to happen, but the day before that Pinocchio gets tempted off to the Land of Toys, where he gets turned into a donkey because he is such a lazy layabout. He gets sold off to a circus where he is forced to perform tricks for crowds, and he sees the Fairy in the audience, with a medallion with a picture of himself carved into it. But she leaves him to his captivity.

Some time later, after he has returned to marionette form, and ends up out in the ocean, he spots a Goat with Azure Hair on an island. She beckons for him, but the terrible giant Shark (the origin of Monstro the whale) surfaces. She beckons him yet more, and even reaches out to him and just misses him before the Shark swallows him up. If it were anyone but this Fairy I might believe the “almost” of the helping him was an honest try and fail, but I don’t trust her at this point. And, granted, Geppetto is in the belly of the Shark and Pinocchio is able to rescue him there, but instead of just sending Pinocchio in after she could’ve just helped Geppetto herself. She does have magic, after all. The Fairy can shapeshift, and what animal does she turn into to save Pinocchio from a shark attack? A goat. A freaking goat. Seriously.

So Pinocchio rescues Geppetto from the belly of the Shark, and eventually they make their way home. Pinocchio earns the value of hard work and works to make some money which he plans to spend on a nice suit so that his father can see how nice he looks. On his way he runs into someone who had previously worked for the Fairy and they talk:

“My dear Pinocchio, the Fairy is lying ill in a hospital.”

“In a hospital?”

“Yes, indeed. She has been stricken with trouble and illness, and she hasn’t a penny left with which to buy a bite of bread.”

He sends the money he’d saved with her servant to help her out. He returns home and:

After that he went to bed and fell asleep. As he slept, he dreamed of his Fairy, beautiful, smiling, and happy, who kissed him and said to him, “Bravo, Pinocchio! In reward for your kind heart, I forgive you for all your old mischief. Boys who love and take good care of their parents when they are old and sick, deserve praise even though they may not be held up as models of obedience and good behavior. Keep on doing so well, and you will be happy.”

At that very moment, Pinocchio awoke and opened wide his eyes.

What was his surprise and his joy when, on looking himself over, he saw that he was no longer a Marionette, but that he had become a real live boy! He looked all about him and instead of the usual walls of straw, he found himself in a beautifully furnished little room, the prettiest he had ever seen. In a twinkling, he jumped down from his bed to look on the chair standing near. There, he found a new suit, a new hat, and a pair of shoes.

As soon as he was dressed, he put his hands in his pockets and pulled out a little leather purse on which were written the following words:

The Fairy with Azure Hair returns

fifty pennies to her dear Pinocchio

with many thanks for his kind heart.

The Marionette opened the purse to find the money, and behold,there were fifty gold coins!

Pinocchio ran to the mirror. He hardly recognized himself. The bright face of a tall boy looked at him with wide-awake blue eyes, dark brown hair and happy, smiling lips.

He never hears news of the Fairy’s but if she really was sick and had not even enough money to buy herself bread, I think that the implication is that she has claimed to have died. But of course, this is the third time that she’s claimed death in the story, and the other two proved to be complete fabrications (including the elaborate fabrication involving the marble tombstone) so I’m sure she’s still living out there somewhere and will return at some point to plague Pinocchio.

And although there might be some implication that she is the one that makes him into a boy, I am skeptical of that too. It seemed like she just had knowledge about what it took to become a real boy and she shared that knowledge but did not actually cause anything.

This is a cause that I am sympathetic to. I know many people who have suffered through depression. Some who are still fighting through it, some who seem to have met some kind of livable equilibrium, and others who have died at their own hand. So, I heartily support the goals of this game. Most of the time I play games just for fun and for mental/dexterity and for no other reason, but I am not opposed to other goals.

This is a cause that I am sympathetic to. I know many people who have suffered through depression. Some who are still fighting through it, some who seem to have met some kind of livable equilibrium, and others who have died at their own hand. So, I heartily support the goals of this game. Most of the time I play games just for fun and for mental/dexterity and for no other reason, but I am not opposed to other goals.

June 7th, 1995. 1:15am You’ve been traveling Europe for a year. While you were gone your family inherited a house from your weird Uncle Oscar and your parents and younger sister Sam have moved in. You arrive at the new house, expecting a warm welcome from you family, but no one’s there. Why? You explore the house as you try to find out what has happened and where everyone is. You are completely unfamiliar with the house, so you don’t know anything about the layout, how rooms are arranged or anything. The game keeps a handy auto-map to help you keep track of where you’ve been. From time to time you discover a clue that points you to look in a particular part of the house, and the auto-map very handily marks the spot for you.

June 7th, 1995. 1:15am You’ve been traveling Europe for a year. While you were gone your family inherited a house from your weird Uncle Oscar and your parents and younger sister Sam have moved in. You arrive at the new house, expecting a warm welcome from you family, but no one’s there. Why? You explore the house as you try to find out what has happened and where everyone is. You are completely unfamiliar with the house, so you don’t know anything about the layout, how rooms are arranged or anything. The game keeps a handy auto-map to help you keep track of where you’ve been. From time to time you discover a clue that points you to look in a particular part of the house, and the auto-map very handily marks the spot for you. Audio

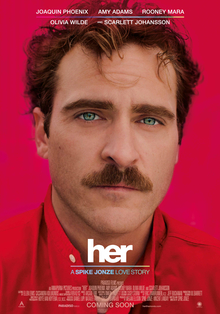

Audio Back in April I reviewed the Ray Bradbury Award nominees for the years as their deadline for nomination approached–I reviewed all the ones I could get my hands on, but there was one movie that wasn’t yet released on DVD–titled “Her” written and directed by Spike Jonze.

Back in April I reviewed the Ray Bradbury Award nominees for the years as their deadline for nomination approached–I reviewed all the ones I could get my hands on, but there was one movie that wasn’t yet released on DVD–titled “Her” written and directed by Spike Jonze.

If you’re interested in the idea of a game that simulates the experience of depression, I recommend instead playing

If you’re interested in the idea of a game that simulates the experience of depression, I recommend instead playing

You work for the government of Aristotska (a country reminiscient of Cold-War era soviet administration), screening people entering the country. Day one is straightforward, because you’ve been told to turn away anyone without an Aristotskan passport. But the government responds to public pressure by starting to allow others through. People start slipping through who don’t belong and the government responds by adding new kinds of documents that you have to check–often checking one document against another for consistent information, checking the sex of the person against the ID (with body scan as a secondary check), scanning for contraband, arresting wanted criminals, etc. You have to pay for food and heat for your family, medicine if your son gets sick, other expenses that you can’t always predict. You get paid for each person you process, but your pay gets docked for making mistakes. The rules change every day, and to support your family you have to be both fast and accurate.

You work for the government of Aristotska (a country reminiscient of Cold-War era soviet administration), screening people entering the country. Day one is straightforward, because you’ve been told to turn away anyone without an Aristotskan passport. But the government responds to public pressure by starting to allow others through. People start slipping through who don’t belong and the government responds by adding new kinds of documents that you have to check–often checking one document against another for consistent information, checking the sex of the person against the ID (with body scan as a secondary check), scanning for contraband, arresting wanted criminals, etc. You have to pay for food and heat for your family, medicine if your son gets sick, other expenses that you can’t always predict. You get paid for each person you process, but your pay gets docked for making mistakes. The rules change every day, and to support your family you have to be both fast and accurate. There are some moments of levity in the game–mostly around one guy who is gleefully criminal. After a body scan turns up something suspicious, you ask him what it is, and his response is “Is drugs!” But much of the game is quite dark, thinking about what it must be like for all these people trying to cross from one country to another, and weighing the ethical decisions when you’re torn between doing what’s right and what’s legal according to the laws.

There are some moments of levity in the game–mostly around one guy who is gleefully criminal. After a body scan turns up something suspicious, you ask him what it is, and his response is “Is drugs!” But much of the game is quite dark, thinking about what it must be like for all these people trying to cross from one country to another, and weighing the ethical decisions when you’re torn between doing what’s right and what’s legal according to the laws.

Speaker for the Dead is the sequel to Ender’s Game. Ender’s Game was first a short story and then was expanded to a novel, and just last year was made into a movie.

Speaker for the Dead is the sequel to Ender’s Game. Ender’s Game was first a short story and then was expanded to a novel, and just last year was made into a movie.