interview by Carl Slaughter

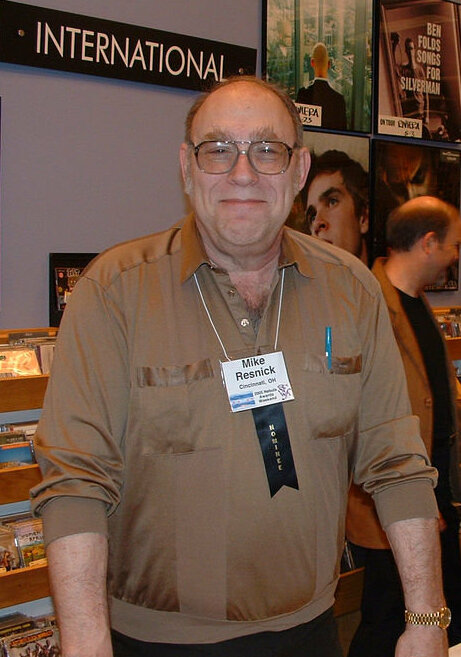

Quick! Who is in second place as the award winner for short fiction (according to Locus)? I have no idea, but it isn’t Mike Resnick. He’s first. Mike has been a writer of speculative fiction for the past 50 years. He has been a writer, an editor, featured speaker, judge for Writers of the Future, father of a best-selling authorâ€the list just goes on and on.

Quick! Who is in second place as the award winner for short fiction (according to Locus)? I have no idea, but it isn’t Mike Resnick. He’s first. Mike has been a writer of speculative fiction for the past 50 years. He has been a writer, an editor, featured speaker, judge for Writers of the Future, father of a best-selling authorâ€the list just goes on and on.

Let’s face it, Mike has done it all (at least everything I wish I could do). He has been one of my favorite authors of all time, and one of the reasons why I still read science fiction today. His novel Soul Eater, was the first paperback I couldn’t put down. His success speaks for itself. If science fiction had a crown for the leading writer, it would be Mike’s head that would be wearing it.

It is not easy feat to be so successful, for so long, in this small corner of literature. Print and publishing has changed dramatically since the days Mike first burst on the scene. The small bookstores I first shopped to find Mike’s writings are all but gone. The big chains that supplanted them are against the ropes as well. Selling fiction, and marketing it, isn’t what it used to be. Our own Carl Slaughter wanted to know what Mike thought about these changing times and wondered what advice Mike had for the up and coming writers. , Frank Dutkiewicz

Carl Slaughter:Â Which conventions are the most worthwhile for an aspiring writer?

Mike Resnick:Â In order: Worldcon, World Fantasy Con, DragonCon. Reason: that’s where you find the greatest concentration of editors. Worldcon is much the best; not only does it draw the most editors from here and abroad, but it has the added advantage that it lasts almost a week, which gives the newcomer more time to make contact.

Carl: What’s the first thing an aspiring writer should do at a convention? What’s the second thing an aspiring writer should do at a convention? Third, fourth, and fifth?

Mike:Â There are things he should do before the convention: try to make appointments to see any editor or agent he wishes to see, and try to find some experienced fan or pro to show him around. Again, I’m speaking of those three major conventions. Most conventions are fun to attend, but totally useless from a business point of view unless you know a particular editor you want to deal with is showing up , and most cons don’t draw any editors at all.

Carl: What’s the best way to approach an editor at a convention? Invite them to lunch with the writer picking up the tab? Hand them a manuscript? Inquire about the type of stories that interest them? Give a quick verbal rundown of a story? Just write down the writer’s website?

Mike:Â

- The writer never picks up the tab.

- Primarily because of that, it’s bad form for a writer to invite an editor to a meal.

- Editors aren’t errand boys, and they’re not at the con to read your manuscript or carry it home with them.

- Simply describe what you’re writing, or planning to write, and see if the editor is interested.

Carl:Â What’s the worst way for an aspiring writer to approach an editor in person?

Mike:Â Bragging, when you’ve few or no accomplishments to brag about, is as counter-productive a way as any. Interrupting the editor when he’s clearly conferring with another writer is another. As in all other endeavors, good manners will get you farther than bad.

Carl: Should a writer break in through 2nd and 3rd tier markets or target 1st tier markets exclusively? If the former, how long does a writer stay in lower tiers before targeting 1st tier markets exclusively?

Mike:Â You don’t hit the moon if you don’t shoot for it. Also, I’m very leery of what you call 2nd and 3rd tier markets. There are professional markets, as defined by SFWA, and non-professional markets, and you do your reputation and your future absolutely no service by appearing in non-professional or semi-professional markets.

Carl:Â Is it possible to become a successful science fiction writer without ever getting a story published in Asimov’s?

Mike:Â Of course. I’d list all the major writers who haven’t sold Asimov’s, but I’m sure you have space limitations.

Carl: Are free markets a good way to build a resume? After all, even free markets choose stories from a slushpile. So a story chosen for a free market has been vetted by a team of editors.

Mike:Â If by “free markets” you mean non-paying markets, the answer is a resounding No. Appearing in a semi-pro or free market is a public declaration that your story couldn’t compete in the economic marketplace, and the very best thing you can hope for is that no professional editor you wish to sell ever becomes aware of it.

Carl: Suppose an editor expresses interest in a story by a new or unestablished writer, but requests a revision that would take the story in a different direction than the writer originally envisioned. Should the writer sacrifice the story for sake of getting a foot in the door?

Mike:Â “Sacrifice the story” gives a false impression: that the novice writer knows more about good, saleable fiction than the experienced editor. That might be true 3% of the time; for the other 97%, the assumption is invalid.

Carl: If an editor requests a major revision, should the writer make the revision on faith or request a contract? Does requesting a contract risk alienating an editor?

Mike:Â No editor is going to give a novice writer a contract based on the good faith that the novice will make the major revision to the editor’s satisfaction. Requesting a contract simply tells the editor you’re a clueless beginner. It won’t alienate him, but you won’t get the contract until the changes are made and he approves them.

Carl:Â Is it fair for writers to expect some type of feedback about why a story was rejected?

Mike:Â No. Back in 1996, I asked the various editors , for an advice column I was writing , how many slush submissions (i.e., unagented, by writers they didn’t know) they received in a month. Asimov’s got about a thousand, F&SF about 750, etc. So the answer, of course, is that the editor isn’t going to give detailed feedback to 1,000 beginning writers a month. The meaningful feedback that he gives to every unsaleable story is a rejection slip.

Carl: Why would a magazine editor ask if an author is published? Shouldn’t the story be judged on its own merits? Isn’t it an injustice to the readers when the criteria is the author’s resume instead of the story’s value?

Mike:Â The criterion for selling isn’t the author’s resume. The criterion for moving up in the slush pile is sometimes the resume. And remember that this is the real world. One reason, for example, that it’s almost impossible for an unknown to sell a novella is because the magazine is in the business of making money, and no professional editor wants to turn over 40% to 50% of his issue to a name he can’t put on the cover, a name that won’t help sell a single extra copy.

Carl:Â Which magazine and anthology editors are keen on new writers?

Mike:Â Any of them will buy a brilliant story from a newcomer. Most would buy a piece of garbage from a Heinlein or an Asimov if they could put his name on the cover. Like I say, this is the real world, and it’s a business.

That said, I have probably bought more first stories than any other editor, but again, it’s a function of the business. When I edit an anthology, and I’ve edited 41 of them thus far, I need 12 to 15 Names I can put on the cover, but that lets me buy half a dozen stories (on average) from newcomers. If I edited one of the digests I could only buy 5 or 6 stories an issue, and I could occasionally sneak in one beginner, one name that didn’t have to pull its weight on the cover.

Carl:Â How can a fiction writer maximize the system to make $750 off a story instead of $250?

Mike:Â People will talk about e-publishing the story, but that doesn’t work for unknowns. There are a million e-stories out there; why should anyone look for yours before you establish a following? The best way to maximum your earnings from a story is to sell it to a major market , either a digest, or one of the handful of “prestige” e-markets such as Clarkesworld, Lightspeed, Subterranean, Tor.com, or another (they change all the time) , and then, with that credential, start selling foreign rights to it. My personal record is 29 foreign and reprint sales for a single story (“For I Have Touched the Sky”; and 28 for “Kirinyaga”), but I average about 5 sales per story, even the less-than-distinguished ones.

Carl: Let’s talk about SFWA. With pro paying markets being so difficult to break into, wouldn’t it make more sense to lower standards to increase membership? What could go wrong with ushering in talented writers who are getting published and getting paid? Wouldn’t broadening membership give the organization more power?

Mike:Â No, the broader the membership, the less clout is has. When I joined SFWA more than 40 years ago, we were a lean fighting machine, boycotting publishers and making it stick, publicizing bad contracts and bad agents, auditing publishers and actually winning hundreds of thousands of dollars in unreported royalties for our members. But we were all full-time writers. Then we stopped insisting on requalification every 3 years, and our membership went from maybe 150 real writers to 1,500, of which more than 1,300 are not full-time writers and do not have the same professional interests as the full-timers. As a result, we are now pretty much powerless to act as an organization whose first duty is to protect its membership, because our membership no longer consists of people who write for a living. We have not conducted an audit in 30 years; we have not publicly evaluated a contract in 25 years; we have not publicly evaluated agents in 25 years; we do not report the average wait time , above and beyond what is contracted for , for a publisher to pay the signature advance, the delivery payment, or to issue the royalty statement; and we have totally disbanded our piracy committee. All this is a direct result of becoming a less professional organization with every passing year and more of a social club, so you’ll forgive me if I think that lowering the standard even more will be anything but deleterious.

Carl: Imagine an editor gets 2 novels. One from a SFWA member, one from a nonmember. The editor is thinking, “If I go with a SFWA member, I risk SFWA intervention, which could result in publishing delays and legal fees. But the nonmember, he just wants to get published, so he’s not going to make things complicated.” Is that a realistic scenario?

Mike:Â Absolutely not. SFWA rarely intervenes, and then only when asked to by the writer , and all other things being equal (such as the quality of the manuscripts) buying from an author with some credentials, however minimal, is certainly no worse, and probably more beneficial to the publisher, than buying from an author with no credentials.

Carl: What about style. Is show really better than tell? Is third person really better than first person? Is narrative really better than dialog and vice versa? Are dream sequences and infodumps really inherently problematic? Is changing POV in the middle of a scene really a cardinal sin? Is white room syndrome really a handicap? Is it really good/bad to use alternate verbs instead of “said”? Is a 3 act play really the best way to arrange a story? Is opening with the most dramatic moment in the story and then rewinding really more effective? ÂShouldn’t the story determine the style, not the style the story?

Mike:Â This is a typical beginner’s question. There’s no right answer, of course. If you write a fine story, whatever you use , first person, dialog, alternate verbs, et cetera , has gone into creating that story. And if you write a turkey using those same things, the fault does not lie with them, but with you.

Carl: A lot of writers swear by workshops. Others see no benefit in workshops. Where do you stand?

Mike: I think most workshops are ineffective. The exception is Clarion , but there’s a reason. In a one-or-two-day workshop I can point out everything that’s wrong with your story and suggest how to fix itâ€but then the workshop is over and you’re on your own. Clarion lasts six weeks, and the instructors can see the story through half a dozen rewrites to its conclusion. Also, Clarion has a different major writer teaching each week, so the students get more viewpoints and opinions to pick and choose from.

Carl: What about online workshops and forums like Critters, Hatrack, WOTF, and Codex. No editors, few established writers, but lots of first readers.

Mike:Â I haven’t attended/taught any online workshops, so I can’t speak to their methodology. I’ve judged Writers of the Future the past three years, and I’d say their roster of successes over the years is every bit as impressive as Clarion’s.

Personally, I prefer working one-on-one with writers. Over the past quarter century I’ve accumulated about 20 of what Hugo winner Maureen McHugh calls “Mike’s Writer Children”. When I find a talented newcomer whose work impresses me, I collaborate to get them into print, I buy from them for my anthologies, I introduce them to editors and agents. I must be doing something right, because 9 of them have been nominated for the Campbell Award, which goes to the best newcomer each year.

Carl: Workshops like Clarion are expensive. Are they worth it?

Mike:Â Meaningless question. They’re worth it if you learn and improve because of them, and they’re not if you don’t.

Carl: At 5 cents a word, can someone who specializes in short fiction ever recuperate the cost of a famous workshop? Wouldn’t they have to win a lot of Hugos/Nebulas and get invited to a lot of conventions to eventually justify the investment?

Mike:Â If their goal is to sell 5-cents-a-word markets for the rest of the careers, they can never recoup the cost. If their goal is to graduate beyond bottom-of-the-barrel markets and they apply themselves, then of course they’re worth it.

And it’s been a fact since the 1950s that you cannot make a living writing short fiction, so of course you also plan to do novels, which are what pay the major bills.

Carl: What about fiction software. Can a computer program really write a story? By the time you fill in the plot outline forms and character development forms, you’ve answered hundreds of questions. Plus the time invested in learning how to use the software. Is it worth it? What about the claim by software companies that 80% of scriptwriters us fiction software?

Mike:Â If you want to be uncreative and write stories that reflect that lack of creativity, I can think of no better way than to use fiction software.

Carl: There is a longstanding debate in the science fiction community. One camp says science fiction writers should strive for literary worth in their stories. The other camp insists the science element is supreme, that the literary aspect is optional, even a hindrance. Shouldn’t science fiction be primarily about exploring the possibilities, results, and implications of science? Aren’t there literary markets for writers who value storytelling over science premise?

Mike:Â There is a school of thought , less and less each year , that says that In science fiction the Idea is king, far more important than the characters or anything else. Then there is a school of thought, to which I belong, that says that in any type of fiction the characters are the most important thing. I feel that if a story makes you think, so much the better; but that if you don’t feel it has failed as a work of fiction. The other side thinks that if a story makes you feel or care, so much the better; but if it doesn’t make you think, it has failed as science fiction. I think over the years my side has pretty much won the battle.

Carl: The science fiction genre has evolved into a very large umbrella with many subgenres. Old schoolers disapprove of most of these subgenres using the term science fiction. They want the genre to change its name to “speculative fiction” and leave the term “science fiction” for stories that are science oriented. Is that a fair proposal?

Mike:Â It’s just a term, and by the way, “speculative fiction” was first proposed by Robert A. Heinlein back in the 1950s. Either is fine with me, but more to the point, I just write the stuff; it’s up to the publisher and his marketing team to decide what to call it.

Carl:Â How long before the only place we can see a print version of one of your stories is in a museum?

Mike:Â Not in my lifetime, but probably within 50 years of its end.

Carl: Several online magazines have experimented with various business models. The Internet has convinced readers they can get online content free. Ad strategies haven’t worked. So what’s the solution?

Mike:Â It’s a conundrum that’s not going to be solved anytime soon. Fictionwise.com proved that there is so much free crap online that readers will pay for reprints by names they know, and Amanda Hocking to the contrary, you’re more likely to make money publishing e-books if you have a following among readers than if you don’t.

Carl:Â Can an ebook become a hit without editors and marketing agents behind it?

Mike:Â Yes, Hocking proved it , but I would say that a conservative estimate would make the odds about three million to one against it being a bestseller, and a couple of hundred thousand to one against a beginner making enough that way to live on. With an established audience, the odds go way down.

Carl: Advocates of ebooks use this reasoning: An ebook can stay online indefinitely, therefore an author can eventually make as much money as a print run, even if it takes several years. Whereas with a print run, the book is off the shelf in a few months and therefore not even available as income. Is this strategy viable?

Mike:Â No. It doesn’t take into account the marketing arm of a publisher who himself is just a cog in a multi-billion-dollar international conglomerate. It doesn’t take into account the fact that, at present, a lot of countries where you can sell your foreign rights for substantial money have so few e-readers that there’s virtually no market for e-books. It doesn’t take into account the fact that almost every book published , paper or electronic — is pirated and available for free on the internet, if you know where to look, within months (and usually weeks) of publication. And of course it doesn’t take into account that a self-published author, whether in paper or phosphors, does not receive an advance, which is what most authors live on.

Carl: Some ebooks advocates are also predicting publishers will become extinct. Is that an exaggeration?

Mike:Â Yes. Some will go under, some won’t. And the smaller presses, who have targeted their audiences, will do just fine. Difficult to sell an autographed, numbered, leatherbound book in electronic form.

Carl: There’s a debate raging over piracy. One side claims tolerating a certain amount of piracy increases exposure. The other side considers this idea heresy. Apart from the moral and legal issues, which side has been vindicated in terms of sales?

Mike:Â Much too early to tell, but I suspect the added exposure doesn’t equal the lost income. After all, if someone reads one of my pirated e-books and loves it, what is he more likely to do , take $25 or $28 and go buy my latest hardcover, or hunt for more of my free pirated e-books online?

Carl: You once said that you make a comfortable living as a writer while your genre friends struggle. Do you have a better financial strategy? A better marketing strategy? More talent? More output? More revision? A better style? More appealing stories?

Mike: Some of my genre friends struggle. Some far out-earn me. Many things go into making a comfortable living as a writer. First, I’ve been at it for just about 50 years, so I have half a century’s worth of contacts, an intimate knowledge of the business, and readerships in countries all over the world. I like to think my stories and books are outstanding, but that’s subjective. Mostly I have a huge output , over 100 books and over 250 stories in this field alone , of material that is at least saleable. I have a top agent. I have editorial contacts all over the world. I have optioned numerous books and stories to Hollywood, and even sold some screenplays, both of which come from a knowledge of how the movie industry works at least as much as from the quality of what I’ve optioned. I have always adjusted instantly to new markets , audio, e-books, whatever. Writing constitutes 100% of my living, so it takes up an enormous amount of my timeâ€and as I have been lecturing beginners for close to half a century, you can be an artist until you type “The End”, but then you’d better morph into a businessman or you put yourself at a huge competitive disadvantage.

Carl: You recently reached your 70th birthday, 50th year in sci-fi, and 50th wedding anniversary. Looking back, what would you have done differently?

Mike:Â I wouldn’t have wasted a whole year being engaged to my wife before I married her. Other than that, no regrets.

Carl: You’ve been writing a lot of sentimental stories lately. What’s the explanation?

Mike: Aren’t old guys allowed to be sentimental? I should point out that my first two awards for science fiction stories in 1977 and 1978 were for sentimental stories, so it’s nothing new. And I should also point out that according to my bibliographer, I’ve sold over 125 funny stories, more even than Robert Sheckley.

Carl: You spend an awful lot of time on the fan circuit. What are the most frequent questions and requests you get at conventions?

Mike:Â The fans want stories about the old days , or at least my old days , and about the giants they never met who are no longer with us. The hopeful writers want to know how to sell and why the world is against them.

Carl: You have more awards than any writer in the history of the genre and you are the most popular living author among the fans. Asimov had a magazine that still bears his name. Orson Scott Card started his own magazine. Robert Silverberg is trying to revive Amazing Stories. Any chance we’ll be reading “Resnick’s Speculative Fiction Magazine” before you retire?

Mike:Â I’d love to see “Resnick’s Speculative Fiction Magazine”, but I’m smart enough not to invest one penny of my money in it, and I have a feeling that sentiment will be shared by every potential investor.

Carl Slaughter is a man of the world. For the last decade, he has traveled the globe as an ESL teacher in 17 countries on 3 continents, collecting souvenir paintings from China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, and Egypt, as well as dresses from Egypt, and masks from Kenya, along the way. He spends a ridiculous amount of time and an alarming amount of money in bookstores. He has a large ESL book review website, an exhaustive FAQ about teaching English in China, and a collection of 75 English language newspapers from 15 countries.

His training is in journalism, and he has an essay on culture printed in the Korea Times and Beijing Review. He has two science fiction novels in the works and is deep into research for an environmental short story project.

Carl currently teaches in China where electricity is an inconsistent commodity.

Carl Slaughter is a man of the world. For the last decade, he has traveled the globe as an ESL teacher in 17 countries on 3 continents, collecting souvenir paintings from China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, and Egypt, as well as dresses from Egypt, and masks from Kenya, along the way. He spends a ridiculous amount of time and an alarming amount of money in bookstores. He has a large ESL book review website, an exhaustive FAQ about teaching English in China, and a collection of 75 English language newspapers from 15 countries.

Carl Slaughter is a man of the world. For the last decade, he has traveled the globe as an ESL teacher in 17 countries on 3 continents, collecting souvenir paintings from China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, and Egypt, as well as dresses from Egypt, and masks from Kenya, along the way. He spends a ridiculous amount of time and an alarming amount of money in bookstores. He has a large ESL book review website, an exhaustive FAQ about teaching English in China, and a collection of 75 English language newspapers from 15 countries.

His training is in journalism, and he has an essay on culture printed in the Korea Times and Beijing Review. He has two science fiction novels in the works and is deep into research for an environmental short story project.

Carl currently teaches in China where electricityÂis anÂinconsistent commodity.

Thanks for a thought provoking interview. Time for me to do some mulling. Mulling, indeed.

Very good interview, enjoyed the questions as much as the answers. Thanks!

Carl,

You posed a lot of interesting questions I’m sure a lot of us would have liked to have asked.

Thank God for the Internet, eh? If you are in China, I assume all this talk was done on-line.