I stare into the endless dark, watching, waiting. It’s like all those years ago, when I was a kid on Christmas Eve. Me, lying in bed, wide-eyed with anticipation, listening for the clatter of eight tiny reindeer landing overhead. Only this time, it’s not jolly old Saint Nick I’m expecting. Nor is it sugar plums that dance inside my head, keeping sleep at bay.

The silent night drags on, one moment melding seamlessly into the next until I think the world must have stopped. Only the stars show me different, each glance out my window revealing their gradual progress across the sky. Then, at long last, it’s over. The dull gleam of first light crests the horizon, and once more, the world begins to move.

“Well,” I say to myself, “Suppose I might as well get ready.”

Heart fluttering with a giddy tingle, I throw back the covers and sit up. Immediately, my poor old bones creak in protest, reminding me to slow down. “Easy, girl. Easy!” I chide, quelling the urge to spring from my bed like some youngster, “No sense in falling and breaking a hip. ‘Specially not today of all days.” I release my impatience with a huff and bob my head in a reluctant nod. Then I plant my feet firmly on the floor, reach for my cane, and carefully hoist myself up.

Once my balance is sure, I begin to move about my home, preparing for the day. There isn’t much to be done. There never is, these days. Still, I want everything to be absolutely perfect. So I throw open all the doors and windows to let in light and fresh air. Then I busy myself with one last tidying-up, straightening the bed, sweeping the floor, and wiping a rag over any surface that might have collected dust overnight.

The next time I look up, my heart skips a beat. Slashes of crimson and gold have already begun to streak the sky. It won’t be long now. Going to the front door, I search the skeletal remains of what had once been a thriving subdivision with bated breath. “Today is the day,” I insist, the words hissing through my teeth like a prayer, “Surely, today is the day.”

I sweep my eyes back and forth for only a moment longer before spying what I seek. There, where the empty street curves out of sight behind a thinning copse of bone white trees, is the stark outline of a shadow. A shadow with which I am now quite familiar. Every morning, it appears on my horizon and, throughout the day, makes its slow approach. When the sun sets, it runs away, but by the next morning, it’s back again, a little closer than the day before. Yesterday, it nearly reached my doorstep before it turned and fled. “It has to be today. It has to!”

Knowing there’s not much time left, I go to my bookcase and take down the lone photo album occupying its shelves. I turn it over and over in my hands, slowly tracing my fingers over the familiar creases in its soft, worn cover. When at last I crack it open, I do so with my eyes closed, breathing deep the sweet, musty tang wafting up from its yellowed pages. Then I open my eyes again and finally allow myself to look at the smiling ghosts trapped within.

An old pain twinges deep within my chest at the same time that a smile tugs at my lips. “Hello, loves,” I say, “It’s been too long, hasn’t it?” I gently turn the album’s pages, pausing to touch the faces captured in each photograph. “Yes, far too long indeed.” When I finish going through and greeting them all, I shut the photo album and clutch it tight to my chest. “But it won’t be much longer now,” I promise, “I’ll be seeing you soon.”

As the words leave my mouth, I am again seized by a giddy feeling. “Soon,” I say to myself, as though repeating the word will make it that much more real to me, “Soon!” Bolstered by my own words, I stand a little straighter and even allow myself a small, excited grin. Returning the photo album to its shelf, I let go my last earthly treasure. There’s only one thing left to do now. Just one last thing. Filled with a sense of renewed determination, I turn to go outside.

“Good heavens!” I cry, heart leaping into my throat when I see the pintsized, hooded figure now standing in my doorway. Thinking I’ve lost track of time again, I ask, “Is it that late, already?” and glance over its head. The sun’s bright eye meets my gaze through the open door. “Oh,” I say, understanding dawning with a bittersweet twinge of disappointment, “You’re early.”

“No, not early,” the figure sighs with a soft, mournful wisp of a voice, “Quite late, actually.”

“Ah,” I say, not entirely sure how to respond, “Well I’m sure you had your reasons.”

“Reasons,” replies the figure, a tremor now audible in its voice, “Excuses.”

“You’re here now,” I try, “That’s what’s really important, right?”

In a gesture reminiscent of a sullen child, the figure twitches its slumped shoulders in an indifferent shrug. I wait for it to say something, but no word comes, and soon, the silence grows awkward. I’m not really sure what it is I envisaged for this moment. A word or a beckoning hand. I just know I’m waiting for something. Anything. But the figure says nothing, does nothing, and we just stand there facing each other, a chasm of silent expectation growing ever wider between us.

Keen to go, my impatience starts to get the better of me. I begin to wonder if I shouldn’t say something. After all, maybe it’s not just me that’s waiting. Perhaps I need to give some sort of sign to show that I’m ready. “Or,” my second-guessing mind whispers. Or maybe I was wrong about today. Maybe my time hasn’t come after all. Maybe it never will. “Or,” it whispers again. Or maybe it already has. Maybe my time came and went long ago. Maybe I’ll wait here forever, suffering in this lonely hell. “Or.”

Panic twists my stomach into a knot and tightens its claws around my throat. I struggle to catch my breath, my lungs dragging painfully, desperate for air. My mind whirls, and I feel myself slipping into a tailspin. As the room seems to tilt around me, I squeeze my eyes shut and hold onto my cane for dear life. It is then, just as I think the chaos will devour me whole, that a sound cuts through the silent screaming in my mind, the soft sobbing of a weeping child.

Opening my eyes, I cast about for the source of the sound. But my home is empty. Nobody else is here. Nobody but me and my strange, small companion. A closer look shows me that it is, indeed, my visitor who weeps. Its shaking form is evident, even beneath the concealing folds of its several-sizes-too-large robe.

As I look at the pitiable creature trembling in my doorway, my panic loosens its grip upon me, giving way to another emotion. One I have not felt in far too long. Compassion. “Oh, come now!” I say, “No need for that! Here, why don’t you come in and sit awhile with me. It’s been a long time since I’ve had anyone to talk to.” Moving to my kitchen table, I slowly lower myself into one of the two chairs I had already pulled out in preparation for today. When I look up to see that my visitor has made no move to join me, I gently add, “Besides, you’re already late. I’m sure it won’t matter if you’re a little later.”

My words apparently afford some small measure of comfort. Though my visitor still hesitates in the doorway, its sobbing subsides into a quieter snuffling. “I suppose that’s true,” I hear it say, pinpricks of hope stippling its muffled words, “Maybe if it’s only for a moment or two.” Then, as though expecting to be struck by a divine bolt of lightning, the figure ducks its head, hunches its shoulders, and takes one tentative step forward. Then another. Then another. When it at last climbs into the empty seat next to me and still nothing happens, it allows itself to relax once more.

“So,” I start, only to discover I haven’t actually thought of what to say, and thus petering out with a lamely trailing, “so…” A moment later, I open my mouth to try again, but having failed to solve the initial problem, am forced to shut it once more. Again and again, this cycle repeats itself, resulting in a long silence that my visitor shows no intention of helping to break. Until, at last tiring of my tongue-tying indecision, I throw all caution to the wind and begin spitting out my every thought as it comes to mind.

“Huh. Well what do you know. Here I am with someone to finally talk to, and I can’t seem to find a single thing to say. It’s not like I don’t have anything to say. I’ve got loads to say! I just can’t seem to decide where to begin. After all this time to think about it—and believe you me, I’ve had plenty of time—you’d think I’d have that part figured out. And maybe I did, once. But now that it’s come to it, I just don’t know. I just don’t know!”

Laughing softly to myself, I shake my head and give my silent companion a wry smile. “Sorry, kiddo. Guess I’m a little out of practice with this whole conversation thing. What about you? What’s your excuse?”

A beat passes in silence. Two beats. Three. Just as I am ready to give up waiting for a response, my companion shrugs and says, “You humans don’t usually want to talk to me.”

“Really?” I ask, genuinely surprised, “Why not? I’d think they’d have all sorts of questions for you. I know I do.”

Another stretch of silence, then, “Some have questions. But they’re usually the kind I can’t answer.”

“And the ones you can?”

“They still don’t often lead to a conversation. Demanding. Cursing. Pleading. But not a conversation.”

“O-Oh. I…I see.” I falter, unsure of where to go from there, but I’m saved the trouble.

“But most people,” my companion continues without prodding, “don’t say anything at all. They can’t. They’re too shocked or sad or scared. And besides, I don’t get to be with any of them that long. So by the time they realize there’s nothing to be afraid of, it’s too late to talk. They’ve already moved on.”

As I listen to all of this with rapt interest, I become aware of a sensation like a knot being loosened within myself. It starts in my chest, works its way up the muscles of my neck, then spreads into my shoulders and down my back. I’m free, I realize. Free of a weight I hadn’t even realized I was carrying. Free of a fear that I’d long ago buried and forgotten. The very same fear that I now recognize being reflected in the figure sitting next to me.

“Sounds like lonely work,” I say, “Must be tough.”

“Yes, sometimes, but I don’t mind,” it replies, a new vitality entering its voice so that it practically gushes, “After all, I was made for this work, and it for me. Only I can do this. No one else was made to endure the responsibility. And besides, the reward more than makes up for the hardship. I know it might be difficult for you to understand, but there’s nothing quite like the sight of a soul when it realizes it’s been brought home. Nothing quite like it at all.”

“I can only imagine,” I say, wondering what sort of expression now hides behind the cowl, “It sounds like you really love your work.”

“I do,” enthuses my companion, then more subdued, “I did.”

“You did?” I question, a touch incredulous, “You mean to tell me you don’t love it anymore? I find that hard to believe.”

“Oh, no. Never that,” assures my companion, “Never that.”

“Then…?”

For a long moment, my companion doesn’t answer, picking at its robes in silence. Then, in a voice so quiet I almost don’t hear it, it slowly whispers, “I always knew, even from the very beginning, that it wouldn’t last forever. That my work…my role…my purpose…would eventually end.”

“End?” I repeat, slow to understand, “But wait…then wouldn’t that mean—?”

“Yes,” interjects my companion, anticipating my question before I even fully realize what it is I’m asking, “It is exactly as you suspect.” Then, without warning, it begins to speak in a foreign tongue. “KAÌ Ὁ THΆNATOS KAÌ Ὁ HAÍDĒS,” it says, its tone deepening and expanding, “EBLĒTHĒSAN EIS TḖN LIMNÉ TOŨ PYRÓS.” Its voice continues to grow, reaching a powerful timbre of such magnitude that the walls around me begin to shake. “OὟTOS ESTIN.” And though I cannot understand the words, “Ὁ DEÚTERÓS THΆNATOS,” they reverberate through me, speaking to my very core.

In the silence that follows, my ears ache with a painful ringing. For a moment, I fear that I have gone deaf. But then I hear my companion, in a low voice, say, “Then Death and the Grave were cast into the lake of fire. This is the second death.” Almost as an afterthought, it adds, “The last death.”

“The death of Death,” I murmur, at last understanding. I pause, contemplating this new development, then ask, “So I really am the last?”

“Yes.”

“I see,” I reply, inwardly marveling at how calmly I accept this confirmation of my long-held suspicions, “I had thought so, but there was no real way for me to know for sure.” I pause again, longer this time, reluctant to ask my next question. Finally, though, I manage, “So if I am the last, then that must mean when I…” Here I stumble, unable to bring myself to say the word. “…you also—?”

“Yes.”

This time, the confirmation hits hard, and I am unable to say anymore for a long while. When I finally do find my voice again, it comes out weak and fearful as I ask, “Is that why it took you so long to come for me?”

The silence that follows is all the answer I need. All at once, I am overwhelmed by the powerful sense of relief that washes over me. Dropping my face into my hands, I cry, “Thank God! Thank you, thank you, God! I had thought that maybe…but no. Thank you, Lord. Oh thank you, thank you, thank you!”

I continue like that for a time, letting out all my years of built-up feelings in a catharsis of tears. When I at last finish crying out all my fear, doubt, frustration, and despair, I dry my eyes and start, “I’m sorry, I—”

“No,” interrupts my companion, its tone heavy with shame, “It is I who should be s-sorry.” Voice breaking on this last word, it sobs, “I’ve been so afraid. I let my fear get in the way of my duty and have caused you such suffering. I’m so sorry. So, so sorry for what I have done to you.”

I listen to these profuse apologies in solemn silence, unsure how to accept them. Part of me is tempted to wave them away with a blithely assuring, “It’s okay,” but that would ring false. Because the truth is it isn’t okay. It hasn’t been okay for a very long time. So rather than try to bandage over my pain with comforting lies, I instead reach out in the spirit of solidarity and say, “I think we all do sometimes. I know I’ve said and done things I’m not exactly proud of, all because I was afraid.”

“But you’re human!”

“And you’re…well, I guess I don’t really know what you are…but you’re not God, are you?”

“No.”

“Then I think it’s probably fair to assume that you’re forgiven a mistake from time to time too.”

“Maybe,” my companion relents, though still sounding unconvinced, “I don’t know.”

“Well why not? You’re sorry aren’t you?”

It nods.

“And you’re here to repair your mistake, aren’t you?”

It starts to nod again, then hesitates.

“You are here to repair your mistake,” I repeat with a jolt of panic, “Right?”

It hesitates another moment, then finally dips its head, finishing its nod.

Releasing my held breath in a nervous laugh of relief, I say, “Well that’s all anyone can really ask for. Just gotta give it our best shot and trust God to take care of the rest.”

Speaking slowly, painfully, as though each word is a struggle to say, my companion admits, “What you say is true, but…” Its voice lowers to a whisper. “…but I am still afraid.”

Leaning forward, I reach out my hand and, with a small smile, whisper, “Me too.”

For a long moment, my companion sits there, staring at my outstretched hand. Then slowly, ever so slowly, it reaches out and takes my hand in its own. The moment our hands meet, my companion finds its courage. Before my very eyes, it undergoes a sort of transformation, straightening its back, squaring its shoulders, and lifting its head. Then, taking a deep breath, it looks me in the eye and bravely quavers, “Y-You have nothing to be afraid of. I-I’ll stay with you every step of the way.”

“And I with you,” I promise, giving its hand a gentle squeeze, “I’ll stay with you too. Every step of the way.”

“O-Okay,” it stammers, with a small frantic nod, “I-I’m ready.”

“Okay,” I say.

Getting to my feet, I help my companion down from its chair. Then, hand in trembling hand, we walk to the front door. When we step up to the threshold, we are met by a vision so breathtakingly glorious that I am momentarily stunned to stillness. As I look upon this final sunset, I am filled to overflowing with a profound sense of peace. I am ready.

We look at each other then, my companion and I.

“Together?” I ask.

“Together,” it agrees.

Then, holding fast to each other’s hands, we cross the threshold and step into bright, burning light.

© 2018 by Sahara Frost

Author’s Note: I originally wrote this story in response to a call for submissions from Zombies Need Brains. They were looking for short stories to publish in a few themed anthologies, including one dedicated to exploring Death as a character. From the moment I read the prompt, I knew that I wanted to write Death as a sympathetic character, particularly as a child (or at least a child-like entity). The idea for my short story didn’t fully form, though, until I stumbled across a Bible verse in Revelations that describes Death being thrown into a lake of fire at the end of days. When I read that verse, I suppose you could say I felt a bit of sympathy for Death. The lake of fire struck me as a pretty raw deal for someone just doing their job. I thought about how if that was the future waiting for me, I would probably be living in constant terror. With that, an idea began to grow in my mind, and my story came to life.

Sahara Frost grew up in the foothills of Tennessee, reading anything and everything she could find. When books were not enough to feed her ravenous imagination, she began to write her own. An M.A. in English and an M.S. in Information Science later, she now supports her reading addiction by daylighting as a librarian while staying up all hours of the night to pursue her real job: writing fantasy. Fortunately, her supportive husband tolerates her many obsessions and makes sure her coffee mug stays full so that she can continue writing.

Sahara Frost grew up in the foothills of Tennessee, reading anything and everything she could find. When books were not enough to feed her ravenous imagination, she began to write her own. An M.A. in English and an M.S. in Information Science later, she now supports her reading addiction by daylighting as a librarian while staying up all hours of the night to pursue her real job: writing fantasy. Fortunately, her supportive husband tolerates her many obsessions and makes sure her coffee mug stays full so that she can continue writing.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is a classic science fiction/fantasy novel written by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson (also well known for writing Treasure Island), first published in 1886. I’m assuming most people are familiar with at least the basic premise of the story, which is not actually evident until about 2/3 of the way through the novel, but I’m not going to avoid spoiling a 130-year old book whose premise has been spoofed so many times in pop culture.

The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde is a classic science fiction/fantasy novel written by Scottish author Robert Louis Stevenson (also well known for writing Treasure Island), first published in 1886. I’m assuming most people are familiar with at least the basic premise of the story, which is not actually evident until about 2/3 of the way through the novel, but I’m not going to avoid spoiling a 130-year old book whose premise has been spoofed so many times in pop culture.

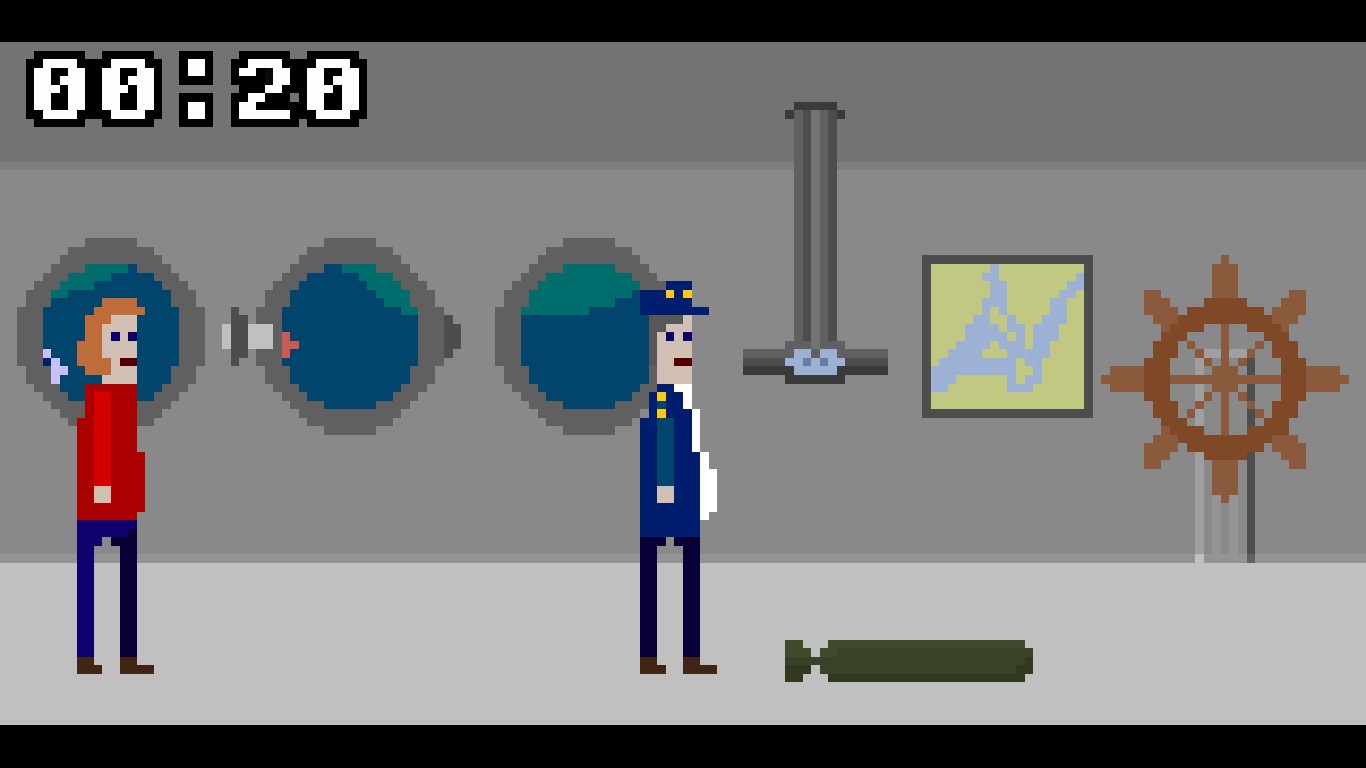

The controls of the game are very simple–a 20-second timer is counting down, but you have plenty of time to try something, anything, which you do by clicking on objects in the scene. In many cases the bomb is not even visible so you don’t always even have a clear objective, but your path is the same–try clicking on everything.

The controls of the game are very simple–a 20-second timer is counting down, but you have plenty of time to try something, anything, which you do by clicking on objects in the scene. In many cases the bomb is not even visible so you don’t always even have a clear objective, but your path is the same–try clicking on everything. Visuals

Visuals

Visuals

Visuals Story

Story

Using bodies as stepping stones to cross spike pits, to weight down switches, or to scale spike walls, new puzzle components are added every few levels to keep things fresh, though the game felt too drawn out at times so that the level felt somewhat repetitive.

Using bodies as stepping stones to cross spike pits, to weight down switches, or to scale spike walls, new puzzle components are added every few levels to keep things fresh, though the game felt too drawn out at times so that the level felt somewhat repetitive. Challenge

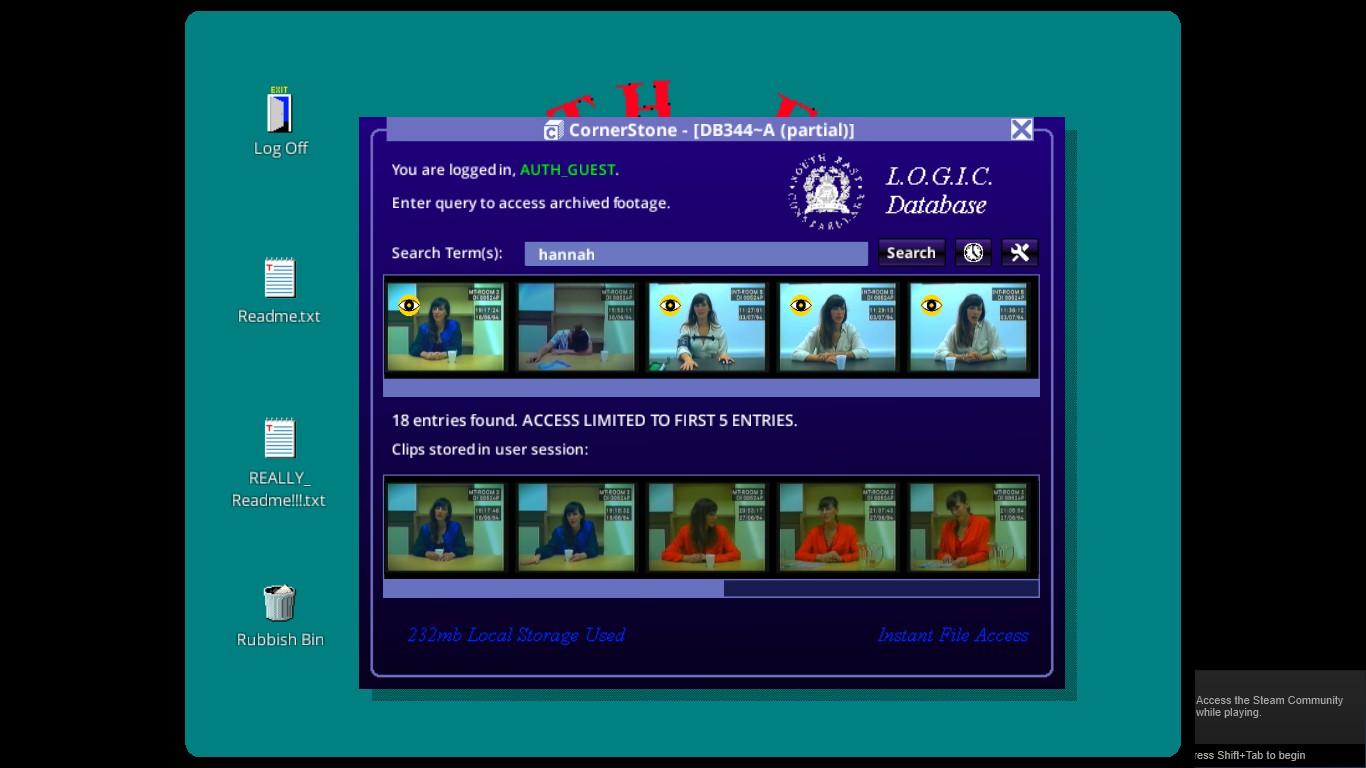

Challenge Her Story is a keyword searching mystery game developed by Sam Barlow and released in 2015.

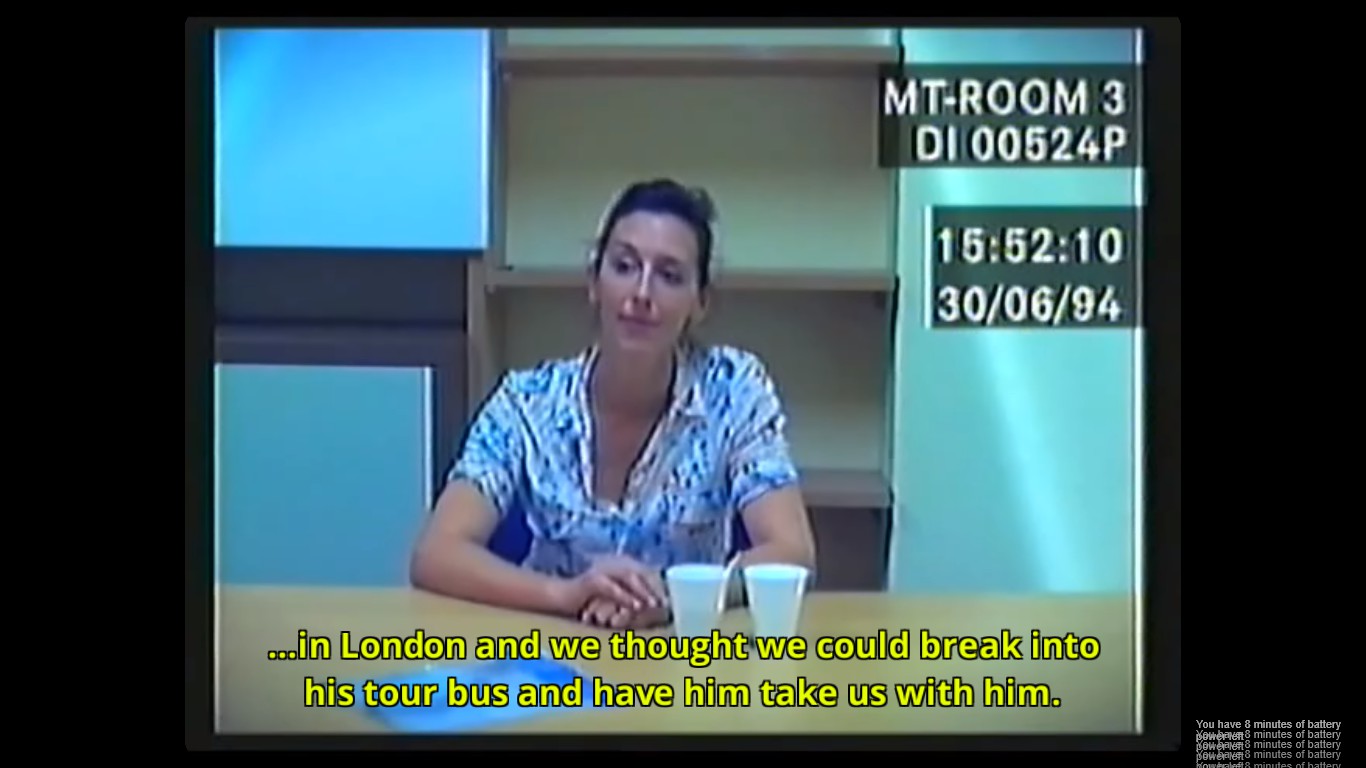

Her Story is a keyword searching mystery game developed by Sam Barlow and released in 2015. What actually happened? If you can find enough of the videos in the database, taken from 7 different interviews, you’ll be able to piece together the story and figure out everything. As you learn more you will gather more ideas about what to search for–people’s names, location names, or key objects that might be referenced as evidence are all of especial importance, since those are likely to be the topic of interview questions. The game is finished when you have watched enough of the videos to piece together what happened–you can keep playing to find all of the videos if you like.

What actually happened? If you can find enough of the videos in the database, taken from 7 different interviews, you’ll be able to piece together the story and figure out everything. As you learn more you will gather more ideas about what to search for–people’s names, location names, or key objects that might be referenced as evidence are all of especial importance, since those are likely to be the topic of interview questions. The game is finished when you have watched enough of the videos to piece together what happened–you can keep playing to find all of the videos if you like. The game is a really interest take on storytelling, watching a story out of order and told by a possibly unreliable narrator. You hear the story in associative order rather than chronological and that makes it quite interesting. It makes you think about the problems with hearing just part of a story out of context. Trying to think of new keywords to search feels sort of like you’re participating in the interviews, trying to figure out what questions to ask.

The game is a really interest take on storytelling, watching a story out of order and told by a possibly unreliable narrator. You hear the story in associative order rather than chronological and that makes it quite interesting. It makes you think about the problems with hearing just part of a story out of context. Trying to think of new keywords to search feels sort of like you’re participating in the interviews, trying to figure out what questions to ask.