The whole family wants to know when Mia is going to walk through the door, but no one has asked her about it. No one will.

The front door of Mia’s parents’ house is painted emerald green on the outside, off-white on the inside, with a knob contrived to look like real brass. No one has opened it for six months. Mia hates that door, has hated it for its full half-year of disuse. Ever since the front door of every house on the street became a portal into death.

Or a portal to somewhere else, at least. But it’s the dead who walk through from the other side. The Garcias’ stillborn little boy was the first one to come back, crawling through their open door as a fat, cheerful one-year-old. George Bojanek, who died of a heart attack three years ago in May and who was buried in the military cemetery at Fort Custer, strolled through one day. None of them have anything to say about where they’ve been and how they came back, certainly not the one-year-old and not old George and no one in between.

The doors are a mystery, but the trick of operating them is not. All it takes is someone opening the door from the inside of the house and walking out. And disappearing forever. Dead, Mia supposes. A cosmic tit-for-tat. But no one knows where George Bojanek’s elderly mother-in-law is now, and the Garcia baby certainly can’t tell what happened to his mother’s little niece.

The doors are almost all anyone can talk about these days, though their voices drop when Mia walks into the room. Yes, the doors are inscrutable, but to Mia they’re also infuriating. She visits her parents’ home as infrequently as she can, preferring to keep to her own apartment in her own town, where the doors are just doors and the only expectations hung on her are that she will arrive at work on time and get things done while she’s there.

But whenever she parks on the too-familiar street for a visit, she has to walk around and enter the house through the garage. When the postal carrier rings the bell to announce a package, it means finding shoes and making the tedious trip around. And each time Mia finds her mother standing in the doorway of Allison’s room, pretending to close the door as if she hasn’t been standing there staring into the darkness for hours, she has to pretend she didn’t see as she walks past to the bathroom.

It’s Allison’s room now, and it always will be. Once, it was Mia and Allison’s. For fifteen years, it was. Mia has had the privilege of having her own room, elsewhere. A series of rooms. A dormitory, a studio apartment. Briefly, a roomy space in Lee and Amanda’s attic. White walls, blue, gray. Her scenery has changed; Allison’s has stagnated in three static shades of pastel green with white geometric-patterned curtains, ones that fifteen-year-olds must have considered the very height of style. Softball and Science Olympiad trophies still line the bookshelves. No dust. That much at least is different from how it was when it was still Mia’s room too.

Mia goes into the room sometimes, when she thinks her mother isn’t looking. She’s not certain it would start a fight, but she’s not certain it wouldn’t. She has as much right to be here as anyone. It was her room too, once. And it’s not as if Allison is here to object. She sits on the bed, rumples the spread. Thumbs through the copy of 1984 on the nightstand. Allison liked to say it was her favorite book, though Mia was certain she never actually read it. She flips to the first page and reads: the clocks were striking 13. She slams it shut and throws it back into its place. It slides to a rest against the white plastic base of the bedside lamp.

Sometimes, often, Clayton is downstairs, playing video games with Mia’s younger brother Brandon. Like Allison’s bedroom, Clayton is a relic left untouched in the wake of her passing. If Allison were still here, Clayton certainly wouldn’t be. She would have outgrown him, like she would have outgrown those atrocious curtains. Someone should have outgrown Clayton, because he doesn’t seem to be aware that he ought to have outgrown himself at some point in the last eight years. At least he’s of more utility than the sepulcher of a bedroom. Brandon likes him, anyway, and he’s nice to the kid. And if Mia’s parents aren’t going to discuss the fact that Clayton was the one driving the car that night, then Mia certainly won’t broach the subject herself. Mia was the one who didn’t insist Allison wear a seatbelt. She was seventeen minutes older, and thus, her sister’s keeper. Nothing to keep anymore, except a silent green room and an old boyfriend with male pattern baldness.

There are pictures of both of the twins in the house—all three children, with baby Brandon making his debut during Mia and Allison’s second-grade year. It’s a polite fiction, the window dressing on the household’s grief. No one has ever come to the library in Rochester where Mia now runs the children’s section. But every year, the whole family makes a pilgrimage to Ann Arbor to visit Allison’s first-choice college and med school.

On her birthday—their birthday, Allison can keep their childhood bedroom but not this, not the entire day—there is no party planned, no bright-colored envelope waiting in the mailbox at Mia’s apartment. She bakes her own birthday cake using a box of Betty Crocker mix, as she’s done the past seven years. She adds extra butter to the store-bought frosting to make it taste more like the stuff her mother used to make. No candles. They seem like a waste. She leaves the finished product on her kitchen counter, untasted, before she heads over to her parents’ house for a silent, miserable Saturday afternoon. She’ll go out with her coworkers next weekend: Tobin, who runs the circulation desk, has a birthday at the end of the month, so they’ll split the difference. It’s oddly reassuring to share a birthday again.

She lets herself in the side door using her key. She’s had the same one since she and Allison were old enough to come home from school alone. Her key ring has changed, but the locks have stayed the same. Most things have stayed the same in this house. Mia wonders what will happen when Brandon graduates and goes to college.

Her footsteps are light on the peeling linoleum of the mud-room. She leaves her shoes under the bench, where no one will trip on them. Where no one will wonder what kind of shoes Allison would have been wearing today.

The grade door closes silently behind her, and she ghosts through the house in her stocking feet. She peruses the contents of the fridge, peels back the lid on a container of cold spaghetti, thinks better of it. Her mother might have plans for lunch already. In the basement, Brandon and Clayton shout at their football player avatars on the big-screen TV. There was a time when Scott, her own high school boyfriend, was just as much a fixture in the house as Clayton is now. She hasn’t spoken to Scott since graduation. What is he doing today? She can’t imagine him playing video games with a teenager. In fact, she doesn’t want to imagine him at all. Too hard to think of a life that’s not chained in orbit around that single day. She drifts upstairs instead.

The door to her mother’s room is cracked open. Not far: just far enough for Mia to catch a glimpse inside as she comes up the stairs. She can see her mother, facedown on the floor. Shoulders twitching in great silent sobs. Fingers twisted into the rug.

Eight years. Eight years of this. Mia remembers a class trip when she and Allison were nine, to a petting farm on the other side of the freeway. One of the chickens was missing feathers, open sores mottling its head and sides. While the girls stared, another hen strolled over and lit into the wounded bird’s neck with its beak. “Why did it do that?” Mia asked, and the farmer shrugged: “They just can’t let it alone.”

A break in the smothered sobs. Mia’s mother looks up from the cradle of her arms. Her fingers slacken on the much-abused rug. Her stained eyes meet Mia’s. A flicker of recognition, of contact. And Mia wonders: was this an accidental intrusion on her mother’s private pain? Or was the whole scene staged for Mia’s benefit? Is this just another pitstop on the nearly decade-long guilt trip Mia has embarked on?

And does it matter?

Even in nothing but socks, Mia’s heels bang on the wooden stairs. She likes the sound. For so long, she has tried to be a silent presence in this house, neither seen nor heard. An unassuming hitchhiker on the long road to nowhere. It feels good to make noise. She is here. Let them remember that.

Someone calls after her—Brandon?—but too late. Her hand closes on the doorknob; her wrist twists. She looks back over her shoulder. Brandon’s face, too pale, just behind her mother’s shoulder. Just behind him, Dad, close-mouthed and frowning. Her mother’s arm is outstretched, but as Mia turns, it falls back down to her side.

No turning back now. That would be a cruelty to all of them.

Mia closes her eyes. Time to go.

The front door opens, and Mia steps through.

And into the foyer of her parents’ house.

For a moment, disorientation shakes her. This isn’t right: she should be gone. But everyone is still standing there, silent and staring, just as she left them.

But no, this is not the same smothering sameness Mia has acclimated to. This is not her family’s house, not exactly, not entirely. Not the same family she left behind when she walked through the door. Her mother’s arms are still by her sides, but they come up now, and Dad grabs onto the wall for support. Brandon sits down on the stairs. “Mia,” her mother breathes, and when she tries to say it again, her voice shatters.

Mia takes an uncertain step forward, looks back at the door she came through. “No!” her mother cries, and Mia turns just in time to be crushed in those strange, familiar arms. Brandon wraps around them both, his threadbare teenage pride tossed aside for the moment, and both he and their mother are weeping, and Mia doesn’t understand why until Scott comes up the stairs.

She hasn’t seen him for five years, not since senior year, when they parted ways to different colleges and different lives. She’s never considered what her life would have looked like if she’d hung on to her high school sweetheart. Having Clayton around was always enough of a souvenir of those days. “I thought I heard … ” He looks as if he’s seen a ghost, and of course, he has. “She did it,” he says, and that word, she, hangs over Mia like a cold shadow.

All Mia’s mother can say is how much she’s missed Mia, and she tucks the hair behind Mia’s ear: an uncertain, familiar gesture. They want to show Mia the house, and she lets them. They emphasize the sameness, the house as museum or mausoleum, but she already sees it: every untouched crack in the linoleum, all the foot-worn carpeting.

Somewhere during the tour, Brandon ducks out. He returns with a birthday cake from the corner store, a packet of multicolored candles, and a lighter. While Dad is digging in the farthest reaches of the freezer for a theoretical carton of Moose Tracks ice cream, Mia excuses herself to the restroom.

There are no bathrooms on the first floor, and given the choice of basement or second story, Mia moves upward. There are pictures on the walls in the staircase, as she’s used to seeing. Just like she’s used to, the family history depicted there screeches to an abrupt halt: smiling pictures of the twins, baby Brandon, suddenly stop in the girls’ junior year of high school. The final picture on the wall is as familiar as a reflection, and just as strange: a high school graduation photo. But of course, the face under the tasseled black hat is Allison’s, not Mia’s.

The bathroom is at the end of the hall, but she stops first at the only closed door. It opens at her push, and she leans into the doorjamb as she looks inside. No sports trophies here, only hand-made picture books and a third-place ribbon from a high school poetry contest. On the bureau, a dog-eared copy of The Fountainhead. Mia grimaces, turns her face into the doorjamb. The walls are green and the curtains are patterned in geometric black-and-white. She wonders if she will have to sleep here tonight. She looks over the bookshelves: there is no copy of 1984, not that she can see.

She closes the door quietly, but she wants to slam it.

Mia uses the bathroom, splashes water on her face. When she comes down the stairs, the family is waiting for her, with Scott in anxious orbit. They sing “Happy Birthday” to her. She eats cake and freezer-burned ice cream. No one asks her what has happened to Allison, and she does not tell them.

© 2017 by Aimee Ogden

Aimee Ogden is definitely not six angry badgers in a trenchcoat. She enjoys baking, reading comics, weightlifting, and digging cozy burrows. Her work has also appeared in Shimmer, Apex, and Escape Pod. You can keep up with her on Twitter or at her website.

Aimee Ogden is definitely not six angry badgers in a trenchcoat. She enjoys baking, reading comics, weightlifting, and digging cozy burrows. Her work has also appeared in Shimmer, Apex, and Escape Pod. You can keep up with her on Twitter or at her website.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.

Definitely Dead is a romance/mystery/horror novel from 2006, the sixth in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris (which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood). The previous books are all reviewed here earlier on the Diabolical Plots feed.

Definitely Dead is a romance/mystery/horror novel from 2006, the sixth in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris (which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood). The previous books are all reviewed here earlier on the Diabolical Plots feed.

Dead as a Doornail is a romance/mystery/horror novel from 2005, the fifth in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris (which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood). The previous books are all

Dead as a Doornail is a romance/mystery/horror novel from 2005, the fifth in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris (which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood). The previous books are all

Dead to the World is a romance/mystery/horror novel from 2004, the fourth in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris, which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood–this book was used very loosely as the basis for season 4 of the show. The previous books in the series (in order) are Dead Until Dark, (

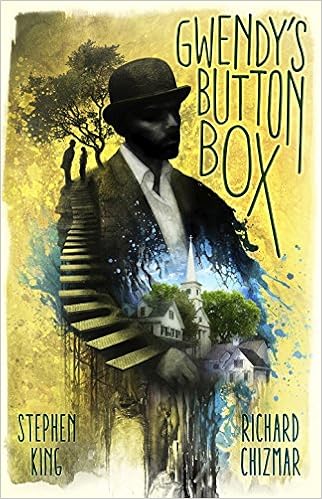

Dead to the World is a romance/mystery/horror novel from 2004, the fourth in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris, which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood–this book was used very loosely as the basis for season 4 of the show. The previous books in the series (in order) are Dead Until Dark, ( Gwendy’s Button Box is a novella written by Stephen King and Richard Chizmar, published by Cemetery Dance Publications.

Gwendy’s Button Box is a novella written by Stephen King and Richard Chizmar, published by Cemetery Dance Publications.

Aladdin is a play based on a 1992 Disney cartoon movie of the same name. The play premiered in Seattle in 2011, and went to Broadway in 2014.

Aladdin is a play based on a 1992 Disney cartoon movie of the same name. The play premiered in Seattle in 2011, and went to Broadway in 2014.

Club Dead is a romance/mystery/horror novel from 2003, the third in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris, which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood–this book was used very loosely as the basis for season 3 of the show. The first book in the series is Dead Until Dark, (

Club Dead is a romance/mystery/horror novel from 2003, the third in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris, which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood–this book was used very loosely as the basis for season 3 of the show. The first book in the series is Dead Until Dark, (