A letter would be waiting for me at home, a real physical letter, like the old days. I knew about it, knew what it would mean, as I rushed through the day, calibrating grading bots and marking AI tests. As soon as I met my quota and had the batteries for my hDevice fully kinked, I hurried down to the great rotating front door.

The grunt whose effort powered the door slipped just as I approached. It shouldn’t have been a problem. Engineers work all kinds of failsafes into the systems so what a grunt does won’t go directly into the connected machine. Supposed to, anyway. But for some reason, the grunt’s tripping translated into an interruption in the door’s power, which made the door jerk. I slammed my shin into it, limped inside.

Immediately the grunt was dragged away and another thrust into its place.

I rubbed my leg as I waited for the door to resume its usual rhythm, then headed out to the street. That time of day the busses had so many stops and starts, they were always unwinding their screws way too fast, having to pause and shove in new ones. Better to walk.

I cut across the university lawn, though it was a longer way. It was where my letter would come from. A letter adding, appropriately enough, a few key letters to my name. PhD, it sounded good added to the end of my name. I repeated it in time to my steps. P, H, D, P, H, D.

The sidewalk passed by the university library’s subterranean power station. In a gesture at humanitarianism that no one would insist on anymore, the power station had a wide, narrow window to let in the sunlight. The glass was angled into the side of a subtle rise, so that from the sidewalk I could easily see down into the station. The grunts worked furiously, kinking and winding the batteries that kept the library’s power-hungry devices running. Treadmills fed power to other machines, those not connected to the batteries. A great, horizontal wheel in the center of the station had a dozen grunts around it, all pushing together to wind up the massive battery placed in its center.

P, H, D, P, H, D. I left the library behind and walked past the campus center. Its clock tower beamed out the time into the air before it, with a ticker of class news and information. I focused on it for a moment, and the words expanded in my eyes. Was it announcing the new candidates? Would my name be there?

If I opened up my hDevice, I’d surely see my name right there. It was smart enough to display that portion of the ticker for me without asking. But I wanted to keep the batteries full, and searching with my eyes wasn’t worth the effort. I let myself enjoy the knowledge it was there, probably even pushed to the front for any friends who passed by. Knowing it was enough.

Across campus, I caught a moving walk. A waste of energy, most places, but gravity and high use by students meant it was one place a kinetic sidewalk made sense. I joined the crowds, watched them peripherally as we strolled along en masse. Did they realize what was waiting for me? Could they see the aura of the PhD hanging over me as I walked? One young man smiled as I passed at a faster pace, a shy smile that I returned. A stunning, older woman gave me a frank grin, which I returned as well. I smiled at everyone, wanted to ask everyone their names. Tell me them all!

I kept quiet, only thought the words. Still, there was a glow to the people around me, as if they could hear me asking, could hear my new title awaiting me at home. Maybe I only imagined it. But maybe my giddy mood did transmit in some way.

I got off the walk a few streets later and had to wait for a two-biker to pass, its grunts straining to pull a full cart of riders. My street was lined with high wires, twisted so tightly they hummed. By night they would all be loose, as we powered our houses through the evenings, the screens and dinners of home life. Then I’d be glad my hDevice was charged. Did I have all the numbers, all the people I’d want to tell the good news? I planned out my order as I walked.

By morning the grunts would have the wires set for breakfast and showers and the morning rush. By then I’d be a PhD for real. My first full day with a title to my name.

I took the steps up to my flat two at a time, and the hollow ring of my footsteps repeated those letters. P, H, D, P, H, D. My finger unlocked the door, and my house greeted me, though its voice was oddly subdued.

“Any deliveries for me, house?”

“Yes, Entity 37-58231-K. One delivery.”

Why my ent number? My house had never greeted me that way since I first moved in. I shrugged it off and looked in the slot for the delivery. There it was, a single envelope. My hands shook as I pulled it out.

It wasn’t labeled as university mail.

It was addressed to Entity 37-58231-K.

Inside was a government letterhead, and a letter that would have superseded any other deliveries of the day. Somewhere, intercepted by the nets and screens of the oversight offices, was my acceptance letter, but it didn’t matter anymore. The government letter was brief, direct. “Entity 37-58231-K, your lottery number has come up. You are scheduled for un-naming. While you retain your name, the government thanks you for your sacrifice for the good of all. Know that it is appreciated. Please report to the nearest courthouse or administrative center immediately.”

The letter dropped from my fingers.

***

When your name comes up for un-naming, you run. Not everyone does. It’s hopeless to flee, and many simply submit. But not you.

Before the letter has settled to the floor, you tear outside the flat, take the steps down at a leap. Are the officials already coming up the elevator? Maybe they’re at the foot of the steps, expecting this. At the second floor, you leave the stairwell, run to a window. It opens stiffly, but wide enough to drop through.

Alleys or main streets? Hiding or blending in? Either has its problems, so you stick with the small street you’re on, run as fast as you dare, as fast a pace as you think you can maintain. No sense sprinting only to have to walk once you’ve gone two blocks.

People look as you run past, but not to stare. A glance, you’re noticed, you’re forgotten…mostly. Forgotten until some official comes asking them. Someone running by? Oh, yeah. Late for a bus, looked like. Went that way. Maybe better not to run at all.

You slow down, ease in behind a group of deskies chatting with each other on their way home from work. Do they have titles behind their names? Unlikely, yet they still have names, and that’s key. They are still people, not grunts toiling away to serve modern society. You will yourself to be one of them, title-less but still named.

A police car passes by. You huddle into your coat, ease in close behind the deskies. The car doesn’t slow.

Still unnerving. When the group passes a thickly wooded park, you peel away. There are trees for cover, and you’re tired. Come morning, the chase will have cooled, and you’ll be able to leave the city entirely behind.

There are rumors of places off the grid, where sun and wind give power and grunts aren’t needed. You’ll find it, somehow. Somewhere out in the wastes you’ll stumble across a hidden settlement. You’ll befriend an odd stranger who gives you the secret, once you show you can be trusted. That’s how it works.

So you sleep, hidden inside the evergreen bushes, where the branches weave together into a perfect hiding place. No one will be able to find you here.

You wake up, stumble away before light, only to find the bush you chose already surrounded by police. Their guns whine with the pent up energy of their kinked batteries, and two grunts stand ready to recharge them.

As if you could ever put up such a fight.

The police grab you before you can flee, before you can swing a single fist or evade a single attempt to tackle you. None of which prevents the police from kicking, hitting, beating you senseless before they drag you away to your unnaming treatment.

***

The grunt trudges. It might well be the only way a grunt is allowed to move, after all. Once the surgeries and incisions are done to slice away a person’s name, it may be the only way it is still capable of moving. No grunts have ever done anything to undermine the idea, anyway.

It takes its place at a great wheel, grabbing the sawdust-coated handle with gloved hands. It does not know where that wheel is. The same one in the university library? Or any of countless others across the city? All identical, and any attempt to remember a named life causes a shooting pain in its brain.

The sawdust keeps the grunt’s hands from slipping off the wheel as it strains with the other workers to push. The device gives off sparks as they move, twisting and kinking as much power into its strands as the weave can hold.

After hours of mindless motion, the grunt is done for the day. Or for the shift, anyway. The lives of grunts are not organized around days but shifts. It enters a cramped dorm off the power station, eats a bowl full of protein-rich paste, and falls into its cot to sleep.

Another shift, some uncounted number of shifts later. The grunt is sent out to gather unwound batteries from drop boxes around the city. The same city where it used to live? Even thinking the question is enough to bring the sharp pain just behind its ear. It keeps its head lowered, lets the streetlight fall on its bare head.

After gathering the contents of two drop boxes, it pauses. The street is open. Has it forgotten that flight to freedom? Those rumors of another way to live? Nearly so, but a glimmer of that dream breaks through its namelessness. It weighs the bag of unwound batteries in its hands. To throw them? Smash some windows? A lifetime of viewing batteries as just shy of sacred holds firm, though, and it sets the batteries down beside the road.

It turns in a circle, a dog checking its internal compass, a beast following a pre-human instinct. But it doesn’t lie down to sleep. It dashes for the shadows of the nearest alley. Unnamed and so not entirely human, it no longer fears the rats and trash that clutter the alley. It slithers into the smallest place it can find.

Alas that the grunts clean the alleys so well. Alas that the humans know to watch for grunts on the run, especially those that are new. Its hiding is brief, and by the end of the shift it is back at its labor. Many shifts will pass before it is allowed outside again, and many more before it goes beyond the sight of a human overseer. By then even the glimmer of memory will have faded nearly to nothing.

Over time, grunts come to resemble each other. The hard labor, poor hygiene, and lack of names melds one into the next. What do minor variations in skin tone or gender matter in the face of drudgery? The grunt that was once Entity 37-58231-K loses the hair on its head, grows dense muscles on its legs and chest. Like all the others. The intelligence and drive that once nearly earned it a doctorate fades from its eyes.

The next time it goes out to gather unwound batteries, it never deviates from its assignment. Most shifts it plods along, turning the great wheel in its assigned power station, never talking and never complaining, even in demeanor. Along with the other grunts, it powers the city. And it watches its fellow grunts fall one by one and be replaced by the newly unnamed. The relentless kinking and twisting of modern life.

Until the grunts rise in revolt.

It starts at the wheel, with a grunt jumping onto the top and grabbing the central axle that rises up to the ceiling. The wheel kinks the grunt, killing it instantly. Its death jolts the rest of the grunts away from their work. At first, for a moment, they might flee in fright. But one —is it the grunt once known as Entity 37-58231-K? We may never know —checks its flight and lets the anger of unnaming rise up.

Anger? It should have been silenced with its unnaming. The humans remove much that made the formerly-named a human, a surgery physical and mental and psychological. Yet the sight of the dying grunt brings a measure of it back, and not only in one grunt. It is as if such strong emotion is a magnet, drawing out the same anger in grunt after grunt, until all roar in voiceless revolt.

They charge from the power station. At first, the humans don’t know what to do. The grunts are unnamed, unthinking, powerless. What can you do, when the machinery of society fights back? More grunts join, leaving behind their tasks. Spinning batteries unwind, and the twisting machines fall still. The more that join, the easier for the next to jump in too.

Then the shots begin. The police don’t hold back. Grunt after grunt falls. But what are bullets except another form of drudgery? Shot, they press on, even after a named person might give up. And unshot, they don’t shy from fear. What mental room they’ve pried open for emotion is filled with mob-rage.

And as they advance, the shooting lurches into uncertainty. How many bullets do the police have? How fully are their batteries charged? And who will they send to get more when they run out? Not a grunt. Even a person, named, must rely on the grunts to rush to the storerooms or face catastrophic delay.

The grunts gather strength, swell in unnamed fury. The police fall back, conserve their firepower, fear their loss of control.

This is it, the time to overthrow, the time to take back names. They move in concert down the street. Where to? It is not strategy but mob impulse that guides them away from the power station and toward the crueler power of the city center.

Here, where so much of the city is run, there is a greater stockpile of kinked batteries and ammunition. The humans find their resolve, form into lines, trust in their guns once more. Even the advantages of namelessness aren’t enough to overcome the firepower of mobilized human forces. They crest, push again toward their oppressors, and fall down. As more fall, the anger ebbs into fear, and grunts fall away one by one.

Our grunt, who once dreamed of a PhD, is still among those who fight, a tightening knot of grunts who refuse to concede defeat. There must still be a way to find the city’s weakness. The grunt falls. No, that’s another of the grunts…maybe. Their identities blur. The knot barges as one around a corner. More fall. Ours? They are too alike to know.

A choice lies before them, a split they must take. One way leads to the place where they had their names removed. Might they still reclaim them? Or make sure no one else loses theirs, at least? The other way leads outside the city, into the wilderness where rumors place other escapees.

They veer toward the wilderness. Too slow, as forces move in to stop them, humans with stronger weapons, sure now in their ability to stop the grunts before they run out of power. The knot nearly comes undone as they waver between fight and flight. Perhaps it is our PhD who pulls them together, forces them toward the unnaming place.

It is locked. Humans with guns move in. This time the grunts do not fight back. They take their places before the door, stand tall in the view of anyone who might see. With arms outspread, they stand, are shot, fall.

No humans lament their deaths, only the disruption.

The revolt is over, the nameless grunts forgotten. But the bullets that mow them down damage the entryway into the unnaming place. No one may enter. For several days, no one is unnamed, just when the city most needs new grunts. Only when human workers are able to repair the door can new grunts be made.

Three days of unnamed silence. That is the only memorial, the only name that remains of the fallen grunts and their brief revolution. But sometimes, at the limits of namelessness, the word only approaches, approximates everything.

© 2017 by Daniel Ausema

Author’s Note: The past couple of years I’ve participated in an event called Wyrm’s Gauntlet, which challenges writers with a series of tasks, winnowing the participants with each round. The final task in 2015 involved a quote about how society relies on stripping us of our identity. I’ve forgotten the exact quote, but at the time is struck me and inspired this story.

A writer, runner, reader, parent, and teacher, Daniel Ausema’s work has appeared in many publications including Strange Horizons and Daily Science Fiction, as well as previously in Diabolical Plots. He is the author of the Spire City series, and his latest novel, The Silk Betrayal, is coming this fall from Guardbridge Books. He lives in Colorado, at the foot of the Rockies.

A writer, runner, reader, parent, and teacher, Daniel Ausema’s work has appeared in many publications including Strange Horizons and Daily Science Fiction, as well as previously in Diabolical Plots. He is the author of the Spire City series, and his latest novel, The Silk Betrayal, is coming this fall from Guardbridge Books. He lives in Colorado, at the foot of the Rockies.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.

Aladdin is a play based on a 1992 Disney cartoon movie of the same name. The play premiered in Seattle in 2011, and went to Broadway in 2014.

Aladdin is a play based on a 1992 Disney cartoon movie of the same name. The play premiered in Seattle in 2011, and went to Broadway in 2014.

Club Dead is a romance/mystery/horror novel from 2003, the third in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris, which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood–this book was used very loosely as the basis for season 3 of the show. The first book in the series is Dead Until Dark, (

Club Dead is a romance/mystery/horror novel from 2003, the third in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris, which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood–this book was used very loosely as the basis for season 3 of the show. The first book in the series is Dead Until Dark, (

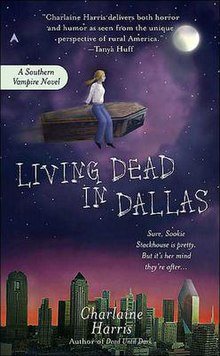

Living Dead in Dallas is a romance/mystery/horror novel from 2002, the second in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris, which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood–this book was the basis for season 2 of the show. The first book in the series is Dead Until Dark,

Living Dead in Dallas is a romance/mystery/horror novel from 2002, the second in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris, which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood–this book was the basis for season 2 of the show. The first book in the series is Dead Until Dark,

Dead Until Dark is a romance/mystery/horror novel published in 2001, the first in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris, which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood (

Dead Until Dark is a romance/mystery/horror novel published in 2001, the first in the Sookie Stackhouse series of novels by Charlaine Harris, which is the basis of the HBO show True Blood ( 10 Cloverfield Lane is a 2016 suspense movie published by Paramount Pictures.

10 Cloverfield Lane is a 2016 suspense movie published by Paramount Pictures.