edited by Ziv Wities

Content note (click for details)

Non-graphic description of significant harm to a child; rioting.If you were a ‘90s kid, you’d get it. Our generation teetered between the days of outdoor activities and Internet fun. Friendship bracelets slapped onto our wrists while “You Got Mail!” and “0 new messages” defined who we were online.

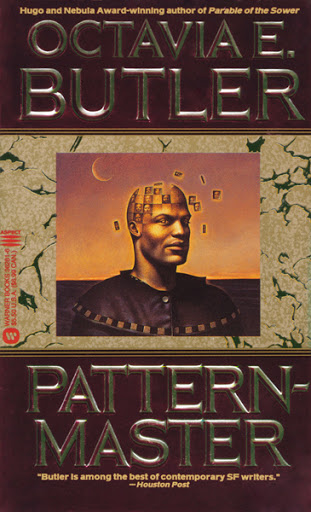

Then there was Donita’s Infernos. You can still find clips of it online, often paired with a clip of Swamp Thing impaling a serial killer.

Memes have recreated one particular scene: Donita Inferno reaches out to a security guard, trying to warn him as a fireball from a rocket is coming their way. I had seen this scene in theaters, and I’d let it rest in my memory for years. The Internet had rediscovered it, flames and all.

The most recent caption read as follows: “Trying to warn Ante Inferno about Rule 34 before he goes online.”

***

I watched the sky while ripping out seams. Airplanes sparked like stars as they made their journeys. A full moon overlooked grimy skyscrapers. Cars screamed through the last dregs of rush hour.

“So the thing they don’t tell you is that if you’re a girl in Hollywood,” the audiobook on my phone whirred, “you are valued by how cute you look in a swimsuit.” I couldn’t hear the next bit over the sewing machine, and then her voice was back: “I felt so embarrassed when they put their foot down and made me wear my red one-piece, which was like-new and fine. Now I keep thinking what a relief it was to have a normal mom and dad. That was the last time I remembered them being normal.”

My hands ached. I reached for my Inferno alien plushie, handmade and a gift from Mairavell2. Technically, I didn’t have a sewing room; I was at home, and I had adjusted the pattern in my tiny bedroom when not helping my dad with his chronic arthritis. It had taken a few months of saving my paycheck to afford the Janome, and then work decided I was no longer valuable. But RocketCon offered no refunds. And I needed an outfit.

I should have been excited to finish my Donita Inferno cosplay. It spread over my desk, shining from every angle. Instead, I kept looking out the window. The plushie squeaked between my hands, as if it was agreeing with the audiobook and me on how weird it was that a bunch of grown men had hosted a pool party for preteen girls.

“I had been invited because I was in a box office hit that should have flopped. But I still had burns on my arms and a buzz-cut since the fireball stunt burned off half my hair.” It felt weird, imagining Donita Inferno caring about being in with the cool crowd at a skeevy pool party. That wasn’t where I’d think she’d want to be.

It definitely wasn’t where I wanted to be. Still no rockets. There were supposed to be rockets shimmering with colorful smoke. They would have shown up, glowing over the streetlights.

The book reached a chapter about the big premiere when my phone pinged. I’ve dreamed of it too, Mairavell2 posted on Tumblr in their reblog. Though I knew the words by heart, I read anyway: a dream of the Infernos sending a message to Earth, to the people. The Infernos were returning from a journey light-years away. They planned to recruit an army to explore the stars, find livable planets, and save humanity. All you had to do was show up in an abandoned clearing. They would handle the little details of location and timing.

I hadn’t dreamed about it yet. But if I had, I would be telling the Infernos to come to RocketCon.

“A stylist had put me in a long-sleeved dress and extensions. You can see me wobbling in heels, clinging to my dad the whole time. This movie nearly killed me, killed my acting career before I could decide if I wanted to act, and I had to pretend that it was great, everything was great. It was supposed to be an honor. The adult actors kept cheering me on. But I noticed one thing: no one else at the premiere covered their arms.”

Kinning was dead. Dream-sharing was in. And yet the sky did not light up with magic. Just stars and airplanes.

***

At RocketCon, people were decked out in space outfits. We attendees and vendors were occupying a hotel ballroom just off the highway. I was tabling for a local author, who’d pay in cash. He did have a reputation for browbeating other creators into joining his company, with loud promises that Netflix would make them famous, but the money helped me justify being here.

The author’s table had a great view of Artist’s Alley, showing celebrities and indie artists alike. I could park with a book while guarding the cash box. The cast for the Doctor Who reboot had the most crowded lines. A real scientist who had served as a consultant for a new Netflix show, Space Fleet Thing, was giving away pamphlets on terraforming moons.

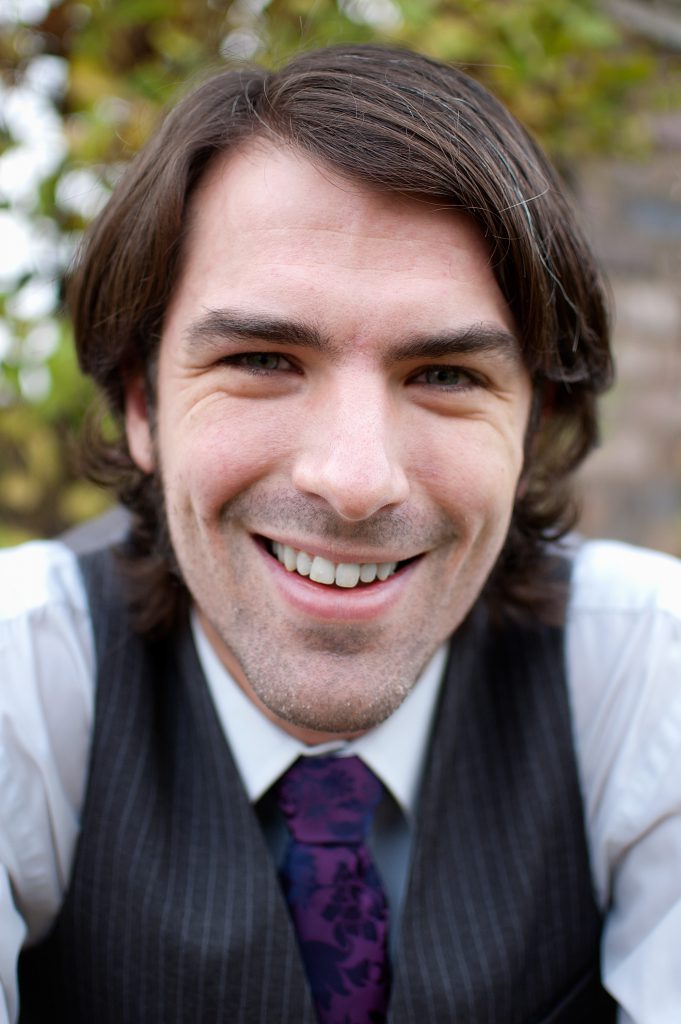

Celestia Marcoh had a short line. When the author came from his Dollar Shop panel and gave me a break, I went over. She was selling copies of her book. Her sundress was bright yellow and black, with marigolds embroidered along the hem.

“Great outfit,” she said.

“Thank you,” I preened. “I made it myself.” I had worked so hard on it, checking and re-checking that the silk and satin matched.

Her eyes noted the flames. She broke eye contact. My cheeks turned pink.

“How are you feeling, by the way?”

“Oh, peachy keen. The coffee in this place is amazing.” She took the print from a pile of them and signed.

“Did you have a hard time getting up here?” I asked.

“No, the drive was okay,” she said. Her voice had a deep warble to it, like she was hiding a laugh. “The pickup handles the highways fine. I don’t know why people complain that this city has the worst drivers.”

I laughed. It made the silk collar flutter.

“Just wanted to say that I’m sorry,” I said.

“For what?”

“I read your book.” Rather, I listened to it on a library app. “I’m sorry that you went through all that.”

Her smile betrayed sadness. She flipped her palm to reveal burn scars running up and down her arms. Irregular red and purple blotches, swollen with age.

“Donita’s Infernos was very influential to me.” I considered the art print. “It got me interested in space travel and physics. I wanted to be an astronaut.”

“Did you become an astronaut?”

“Nah.” I reached for a copy of her book and took out a few twenty-dollar bills. “I didn’t have the grades for it. But I still love outer space.”

Her hands folded the twenty-dollar bills. With the print, she didn’t need to give me change.

“You shouldn’t feel bad that the film gave you dreams and ambitions for a new future,” she replied. “Lots of people have come to me and said they got into astronomy or science because of the movie. Others found their community.”

“They did?”

“Sometimes a person’s dreams are good for them, even if they are another person’s nightmare.” She considered the book. “What’s your name?”

“Vega. Vega March.” So sue me, my parents wanted to give me a unique name.

She signed with a white feather pen. Wisps of plastic feathers shed onto the book like ashes. I read the epigraph that she added to her signature, with plenty of loops.

To Vega: May your dreams come true and set the world ablaze.

***

Fun fact about Celestia Marcoh. She played Donita, but she had never wanted to be in a space movie. Her dream was to be a Disney princess. At least, that’s what she claimed in an interview back in the ‘80s. Later on she noted that while she was five when she said that, her feelings have stayed the same. No one gets traumatized from voicing a princess.

Donita’s Infernos was her biggest role. She did a few sitcoms and one TV movie, but then vanished. You’d be lucky to spot her in a Geico commercial. Seeing her at the con was a godsend.

Celestia’s Falling from The Spaceship talks a lot about how the stunts for the film were done with no safeties, and she almost dislocated an arm. Best known, of course, is how one of the biggest stunts — the fireball scene —was done with real explosives, and she got burned. Her parents sued the studio and got settlement money. While they set some aside for her schooling, they spent the rest while they kept driving her to more acting gigs. And Celestia asserts that she was one of the lucky ones, who drank a little and avoided the heavy drugs. She knew other child actors who had gotten into much worse shit.

Part of the reason that she couldn’t build a career in film was that she still had burns and emotional trauma from the fire. That she wasn’t typically thin and pretty didn’t help. At best, she could be an extra in a romantic comedy—someone who was the butt of the joke while coated in heavy makeup.

She’s not returning to the reboot, by the way. Her co-stars invited her back for a cameo, since they were the only decent people out of the whole mess. They’d match the salary that some of the more famous stars have. No dice; she’s done with that life.

Some other actress will take her place as the new Donita. Or Don, if they change the gender, like some tweets are saying. Lucky bastard.

***

Celestia packed up early. Her pile of books had vanished, though she still had a few straggling prints. She took her time arranging the prints and her poster inside a camouflage-patterned suitcase.

The flame-embroidered collar tightened around my throat. She seemed smaller as an adult, even though she was five foot eight. I had scars too, but no one had given them to me. They had dripped from an accident with a glue gun that I had bought with my own money. It was my own stupidity that had caused my scar. Donita’s burns came from no one caring about her. Sorry—Celestia. No one cared about Celestia.

After helping the author with his supplies and packing up, I walked back to my car, struggling with a heavy tote because someone had been selling a giant green OMGAlien plushie with square glasses, which I couldn’t resist, despite my nonexistent income. He went in the backseat, and I considered buckling him in like a child. Instead, I wedged him into the tote bag and placed it on the floor. Celestia’s book went in the passenger seat.

My phone pinged. I checked it. My bestie Katia, who hadn’t been able to attend RocketCon, sent another meme. The same one with Donita screaming, but a new caption: “NASA telling Inferno fans to ignore the rockets in the sky.”

A flash of silver against the evening sky. I paused, closed the car door, and looked. Shiny smoke. Sparkles and booming swirls of exhaust in the air.

Other people pointed. Some were decked in Inferno capes, and some were wearing polo shirts and jeans. Their mouths opened. Crackling, like static television mixed with thunder, drowned them out; the decibels dripped from the sky. They echoed from the smoke that was too large to come from an airplane.

I texted Katia back, they’re here.

Celestia Marcoh caught my eye; I turned. She was also packing her car, careful to load boxes with display equipment into the trunk. Her jacket snagged on the trunk lid and she had to put down one box to free the button. Our eyes met, and she said something I didn’t catch. Or maybe she was muttering to herself.

The rockets weren’t vanishing. They were lingering in the distance. Other lights went up, flashing. More crackling fading.

I left my car and started walking. Rush hour would be murder, and I knew where I had to go. Find a section of woods out just beyond the city, and spy on an abandoned house. Make sure you see the family testing out their powers. Anyone that tried driving to the rockets would be stuck on the road for hours.

Before leaving the lot, I looked back at Celestia. She waved her arms at the crowd, shouting despite the fact that we couldn’t hear anything. But I could read her lips.

Don’t go.

***

The Infernos were a unique family. They had powers, namely telekinesis and flight. While the boys were good with technology and fixing it, the girls would show their adeptness in combat. Considering this was the early days of CGI, most of the scenes still held strong.

They weren’t quite invisible, but no one would notice them. Ordinary people couldn’t see the Infernos when they were working. Despite the silvery space suits (and the long sparkling hair, in the case of the family patriarch Ante Inferno), no one paid them any attention. If someone did, more than likely that person would get hurt. They would break into space sites, often ones that had launches scheduled.

What was interesting was that while the Infernos were touted as heroes, our actual protagonist Nita, short for Donita, knew they weren’t. She was hiking in the woods nearby and stumbled upon their house when she noticed a trail of silvery moondust leading to their porch. The next thing she knows, she sees kids and adults bouncing in the air. Oldest brother Kai spots Nita watching, and she ends up in the air as well, being tossed around. She’s seen too much, and now she can’t leave. The Infernos recruit her as their latest family member.

Of course, Nita learns that she hadn’t discovered their enclosure by accident. She has the outside element that the Infernos have been missing: the understanding of how the real world works. They’ve been isolated for so long, traveling through space invisible and unwanted, that they’ve long forgotten what people needed.

Secretly, I think we all wanted to be Donita Inferno. We wanted the powers, and for someone to take us away from our ordinary life. Most of the fanfics show that we want to be special, with OC after OC sneaking into the spaceship. We never met outside our stories. There could only be one special Inferno.

***

More footsteps. Other people were also walking, still in their cosplays. They’d left their vehicles behind in the hotel parking lot. And newcomers, too; joining in ones and twos. I saw a girl holding up her phone and attempting to scream into it. Go figure.

The roads were not meant for pedestrians; sidewalks ended without warning. Other cars honked at the people in jeans and homemade space suits and long, flowing wigs. Some drivers clutched their steering wheels and looked like they wanted to run the crowd over.

On another day, I would have understood. But I didn’t want to understand a world where I’d have to go home and wait for my dad to yell that he needed his back rubbed and I was doing it all wrong.

Running was not an option, even though we were in a race. It would take a while to reach the rockets, which seemed larger with the searchlights as they soared over the orange skyline. They were designed to travel faster than light. We only had legs meant for mere mortals.

We walked across the highway in a group, ignoring the cars, the curses from drivers, and our buzzing phones. A cigarette flew from an open window; it bounced off my arm, glowing orange. I barely felt the singe.

Traffic built up behind us as we kept moving. There were a few dozen of us now. I wondered how many were people who had dreamed of rockets from other planets, of alien abductions that would allow them to fly. And just how many had been attending RocketCon, asking the Infernos to attend too. To join an army that wanted them.

Nita hadn’t wanted it. Nor had Celestia. But neither of them had been given a choice.

The sun kept sinking behind the skyscrapers. Bugs came out, no-see-ums and mosquitoes surrounding us. We swatted in rhythm with our walking.

My feet ached. If I stopped, the pain concentrated in the heels. My skin itched and sweated. But I kept up my pace, so I wouldn’t be left behind. We were already closing ranks.

More red trucks stopped us. Not ordinary ones. These had coils of hoses and ladders. I had seen them when cars crashed into cylinders. On television, the hoses uncoiled and spread at burning houses. Here, they just stood in our way.

Behind them, caution tape criss-crossed on the tiny path that led off the highway. So did crowds of bright yellow suits and oversized helmets.

We stopped. The spell didn’t break. Nor did that ping of wrongness surging through my urge to just charge past them.

“The road is closed up ahead,” a firefighter announced through static feedback. “This is a restricted area. Please turn around.”

His helmet lacked a facemask, but it covered his mouth and nose in shadow. Sweat gathered on his brow and dripped. He blinked as some ran down over his brows without stopping. The megaphone shook between two hands.

The staticky voice was the first noise we had been able to hear properly since the rockets had passed, and what it was telling us was ridiculous. This wasn’t restricted. The road is everybody’s. Were they here just to stop us?

Indignant shouts filled the air. I was one of them, argumentative and tired.

“We have the right!”

“Move, you jerks!”

“They promised us the stars.”

“Guys, please be reasonable,” the firefighter with the megaphone responded. “The terrain up ahead is strewn with garbage. It’s acres of fire hazard; we have to contain it before it spreads.”

More indignant shouting. That would be worse, wouldn’t it? If they weren’t even trying to stop us specifically; if we were supposed to just give up on everything because of a bunch of garbage and some fire regulations. No. Our dream was the same one that had been shared across minds and social media. We had the right to follow the rockets, to find what was promised to us.

“Turn around,” he repeated. “There is literally nothing but garbage up there.”

Maybe the guy didn’t mean anything by it. Poor guy and his poor friends. They had put in their time to fight fires, rescue kittens from trees, and treat patients in ambulances. A whole team of them blocked off the path, standing solid; they were imposing, they were equipped. But they weren’t ready.

We swarmed like zombies on a brain buffet. There were a few dozen of us, determined to push forward and find the rockets. RocketCon had forbidden real weapons and set size restrictions for replicas, but blunted metal, foam and wood could do plenty of damage against an unsuspecting target. One six-foot Arsenic Knight swept away batons with the Moondust Blade from the Spaceship Grease franchise, while an anatomically correct Slime Turtle cosplayer rammed against bodies and made them rattle. The 3D-printed shell cracked after the cosplayer side-swept screaming the yellow suits.

They fought back. Of course they did. They’d never say it, but keeping us from the rockets was what they were here for. Some tried spraying us with a hose. Cosplayers dressed in long trench coats toppled to the ground and struggled to get to their feet.

And me? I only had two legs, my phone, and a Donita Inferno cosplay, having packed everything else away in the car. So I couldn’t ram a weapon or a silvery satin outfit against the helmeted sentinels. All I could do was move forward and not lose my nerve. One step, then another. Don’t scratch that bug bite. Ignore the sharp pain and blood running down your cheek. Keep standing.

More sounds drowned out our protests. We looked ahead, and even the firefighters twisted their necks as they tried to hold us back. The rocket landed on the grass ahead of the cars, sparks flying, threatening a blaze. It was bright orange, a replica of the Infernos ship from the movie.

The next effect also came directly from the movie: uniformed men launched into the air. One minute they were spraying the crowd, the next, they were catapulted into the rail-thin trees. The screams were glorious.

We started running, those of us still standing. Not running—sprinting with bloodshot eyes and excitement. The dreams had come to us, promising the truth after years of pining. And I am sorry if I trampled the firefighter whose megaphone sailed into the air and crashed onto the pavement, but I’m not sorry about tearing through the caution tape like it was tissue paper.

The house appeared as it did in the original movie, not in the reboot trailer: drooping shingles and dusty glass windows with cobwebs as decoration.

If the rockets hadn’t drowned us out, we would have cheered. Instead, we ran forward, sweat running down our faces. I didn’t know what we would find in the house or on the orange rocket, but a part of me didn’t care. The Infernos were on that ship. And they would have to take me. Because unlike Donita, or Celestia, I wanted to be the hero, burns and all.

© 2025 by Priya Sridhar

3585 words

Author’s Note: I was dreaming about being a kid hero. But not someone who jumps into the fray. Instead, this girl was kidnapped by telekinetic vigilantes planning to hijack a space launch. When I woke up, it was one of the few vivid dreams I was able to write down and make coherent. But there’s another part to this story: it got me thinking about the many fics I saw in one fandom, where a female OC was kidnapped and brought to the copyrighted world, because she had special powers and was different. There was a catharsis in being wanted by bad people because you are special. But it’s a double-edged sword, especially when considering how a scenario like that would play out in real life. Media raised me. I watched PBS and anything available on public television since we didn’t get satellite TV until 2005, after Hurricane Katrina. But I’ve been disillusioned by just how much so-called family-friendly media comes from exploiting underage actors. It’s not always the case, and I hope Spy Kids avoids that disillusionment. But while attending Chicago WorldCon in 2022, I listened to Jennette McCurdy’s memoir I’m Glad My Mom Died. She explained how Nickelodeon creator and director Dan Schneider, known as the Creator, fostered and enabled a culture of child abuse. McCurdy’s stage mom certainly didn’t help with her emotional and psychological abuse, but she stopped being proud of the work she did on iCarly and Sam & Cat because it was tainted by the lack of freedom on-set and off. Quiet on Set and YouTube brought out more tea about the powerhouse, and Will Wheaton released his essay about how working on The Curse broke his film career and probably damaged his relationship with his parents beyond repair. It’s a feature, not a bug, that kids get hurt creating franchises that people come to love. This story is me thinking about this contradiction, how what inspired me to create has hurt others. And how do we deal with that while wanting to escape our less-than-ideal situations.

A 2016 MBA graduate and published author, Priya Sridhar has been writing fantasy and science fiction for fifteen years and counting. Her series Powered is published by Capstone Press. Priya lives in Miami, Florida with her family.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.

A Wrinkle in Time is a young adult science fiction novel written by Madeleine L’Engle and first published in 1962–it has been adapted for a movie that will come out in March 2018.

A Wrinkle in Time is a young adult science fiction novel written by Madeleine L’Engle and first published in 1962–it has been adapted for a movie that will come out in March 2018.