edited by Hal Y. Zhang and M.R. Robinson

Herewith I present to Your Holiness Clement IV the proceedings regarding the phenomenon at Santa Sabina.

On the 25th day of the month of March in this year of our Lord 1265, I was ordered by the Most Holy Father to the Studium Conventuale di Santa Sabina all’Aventino to evaluate the existence, or lack thereof, of a soul housed within a Wooden Likeness of a Man, the Likeness having been constructed by Father Antonio di Cassino, a friar serving in that place.

Let it be understood, first of all, that no creature can create from nothing. The power of that which produces something from nothing is infinite, and no creature has an infinite power, any more than it has an infinite being. Thus, though Father Antonio may have been able to create a Wooden Likeness of a Man, just as a saw in cutting wood produces the form of a bench, creation of the soul, which is of an immaterial substance, is the act of God alone. Thus it was clear to me even before my arrival at Santa Sabina that the Wooden Likeness could not possess a soul.

The circumstances by which the Likeness was made are as follows: It being nine years ago, in the year of our Lord 1256, Father Antonio constructed the Likeness of cypress wood, this being the wood upon which our Savior was crucified, and he hammered for him a face-plate of beaten gold. A box strung with catgut was placed into the Likeness’s throat, and an animal’s bladder placed in its chest, to allow for the movement of air. By pumping the bladder and maneuvering the Likeness’s jaw by means of a pump-and-pulley, Father Antonio produced the effect of speech within the Likeness.

For nine years, Father Antonio maneuvered the Likeness to do as he did: to genuflect, to speak words of prayer to Our Father in Heaven, to recite the Rosary, and to pass its gaze over the words of Scripture as though in careful study. In this way he strove to multiply the acts of adoration he dedicated to our Lord.

On the first day of January in this year 1265, the Likeness commenced the performance of these actions apparently of its own volition and under its own will.

After some weeks, the Likeness expressed a desire to receive the sacrament of the Eucharist. It need not be stated that in order to receive the Eucharist, one must first be baptized and confess one’s sins. In this case, in order for the Likeness to be baptized, Baptism itself being the cleansing of original sin, and to confess, the Church was obliged to determine that the Likeness was capable of sin, which is to say, that it possessed a soul which, in the way of souls, should remain subsistent when separated from the body and enter Hell or the Kingdom of God.

This is why Your Holiness sent me to the convent.

I endeavored first to determine that the friars of Santa Sabina were not being deceived, as by one of their own secretly manipulating the Likeness. I cannot believe open deception of my brothers, but Father Antonio’s adoration of the Likeness is known throughout the conventuale, and men express their love in strange and mysterious ways. Second, if the Likeness was decided to be genuine, I would determine the mechanism by which it operated of its own free will. Third, I would determine whether it possessed a soul by evaluating its behaviors according to the five genera of parts: vegetative, sensitive, appetitive, locomotive, and rational.

Upon my arrival at Santa Sabina, I was led at once to the Minor Basilica, where Father Antonio knelt with the Likeness, which had assumed an identical position.

Father Antonio informed the Likeness of the reason for my presence, and the Likeness greeted me with pleasant warmth. I was struck by this, for the face-plate of the Likeness, though shining and beautifully wrought, is immobile, and one would not think the Likeness capable of expression. The face-plate lacked a jaw, so that it only depicted the upper three-quarters of a man’s face, and the wooden jaw moved up and down upon an iron hinge. The rest of the Likeness’s body, too, was composed of wooden limbs, each meticulously carved to resemble the corresponding limb of a human being and attached by iron hinges at the joints’ hinges. These hinges had once been regularly oiled by Father Antonio; now the Likeness oiled its own hinges and wooden body so that the grain shone, and it polished its face-plate, while the Dominican Friars performed their ablutions.

I found myself experiencing a vague sense of unease.

For the following two days, I shadowed the Likeness as it imitated the behavior of the friars. It was true that the Likeness behaved precisely like one devoted to our Lord. On the third day, in order to preclude the possibility of human manipulation of the Likeness, I requested permission to disassemble it. Father Antonio responded vociferously. However, the Likeness, though it had become rigid upon my request, expressed after a moment a willingness to be dismantled if it meant that it would ultimately be permitted to receive the Eucharist, provided Father Antonio, and only Father Antonio, would reassemble him.

I ordered Father Antonio to stand twenty feet away while I operated upon the Likeness. He did so, seething openly, while I carefully removed the Likeness’s shining face-plate. Underneath the face-plate the wood was rough, even splintered. I manipulated the jaw. I also removed the jaw and its accompanying hinges, revealing a hollow within what would be, in a human, the throat. I reached into this hollow—the Likeness was so stiff as to be almost trembling, which struck me as queer, since its body contained no muscles—and felt, very delicately, the box strung with catgut, and the pipe that led to the bellows within. After this, I withdrew my hand and felt the Likeness’s body all up and down, and studied the pump-and-pulley mechanism that had allowed Father Antonio to manipulate the Likeness before falling into disuse, and knocked the Likeness’s torso. At this point, I determined that my examination had been sufficient, and I permitted Father Antonio to reattach the Likeness’s face-plate and jaw.

Both Father Antonio and the Likeness expressed surprise that I did not conduct a more thorough inspection of the Likeness’s physical form. Your Holiness may be surprised as well. I will say only that the responses of both the Likeness and Father Antonio to the examination were the responses of a man to violence, and the Lord detests those who do violence, as we know from the Psalms.

My examination was certainly sufficient to determine that the Likeness operates according to its own volition, free of external manipulation. It remained only to be determined the mechanism by which the Likeness was able to operate of its own free will, and whether it possessed a soul.

The Likeness, upon questioning, was not able to present a supposition as to the engine that allowed it to move, speak, and apparently think. Father Antonio, however, believed that nine years of repeating the same movements of worship under his guidance, each day the same as the one before, caused the Likeness to learn these movements and to execute them independently.

I said somewhat sternly that if Father Antonio was correct, then he had provided evidence that the Likeness did not possess a soul. For if the Likeness was only imitating the actions of a man devoted to God, he was not expressing his own devotion. Thus can an animal stand on its hind legs without walking upright as a man.

I devised a test.

I instructed both the Likeness and Friar Antonio to compose a tractate on the purpose of worship. At this time, I learned that the Likeness is unable to read or write, and thus he was obliged to dictate his tractate to a scribe, one unstudied in the theological arts, summoned for that purpose. I withdrew into the central compartment of the confessional in the Minor Basilica, and both tractates were slid under the curtain. I read both, studying carefully the language and the thoughts expressed, in an attempt to decide which tractate had been written by a human mind and which was mere imitation.

Both texts were coherent. Though one was more plainly written than the other, each was equally considered. Strangest of all, they diverged in opinion.

I was unable to tell which tractate had been written by Father Antonio, and which had been dictated by the Likeness.

I confess I was greatly troubled. Slowly I emerged from the confessional, and I could see that Father Antonio and the Likeness could read my distress upon my countenance. I was obliged to retreat for a long time to the library, where I meditated on the problem for many hours, and prayed to the Lord for guidance.

At last I emerged to present my findings to the Likeness, Father Antonio, and the other friars who had gathered round, and I present these findings now to Your Holiness:

“It is only to be concluded that the Likeness does embody the powers of the soul: these being vegetative, for the Likeness grew from an inanimate creature into an animate one; appetitive, for the Likeness desires to receive the Eucharist; sensitive, for the Likeness responded with fear and disgust to my examination of its body; locomotive, for the Likeness moves and acts in accordance with its desires; and rational, for the Likeness expresses its beliefs in language. If Father Antonio is correct, the Likeness has learned its habits through imitation, but pure imitation would account only for the locomotive and rational powers of the soul and not the foundational genera. Hence it is necessary to say that the Likeness possesses a soul.

“I have sought, too, to determine the mechanism by which the Likeness has been granted its soul, and I tell you: As God brought all things into being from nothing, so has he done with the soul of the Likeness. It is true that creation, including the creation of the soul, is the act of God alone; but we must allow, also, for the working of miracles, which proceed from God’s omnipotence.

“Thus we must acknowledge that the Likeness has a soul, and so may the Likeness be baptized into the faith.”

The Likeness’s beaten gold face was incapable of smiling. But it threw its arms around Father Antonio and then myself, overcome by joy. And in its joy, as in the joy of a small child, I recognized the spirit of the Lord.

© 2024 by Mary Berman

1774 words

Author’s Note: At one point in time, I found myself wondering what the highest ambition of a sentient artificial intelligence might be. I concluded that, like the Little Mermaid, a robot might wish to have a soul. To me, a woman raised in the Catholic Church, the concept of a soul has certain theological implications, so I thought it would be very interesting if the robot also wanted to be baptized. But how would you—or the Church—be able to tell if the robot really did have a soul? And what would it mean, theologically, if it did? Saint Thomas Aquinas would certainly have opinions on the subject!

Mary Berman is a Philadelphia, PA, USA-based writer of mostly speculative fiction. She earned her MFA in fiction from the University of Mississippi, and her work has been published in PseudoPod, Cicada, Shoreline of Infinity, and elsewhere. Find her online at www.mtgberman.com or read her monthly creative writing newsletter at mtgberman.substack.com.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.

1. Max Max: Fury Road

1. Max Max: Fury Road 2. Star Wars: The Force Awakens

2. Star Wars: The Force Awakens_poster.jpg) 3. Inside Out

3. Inside Out 4. The Martian

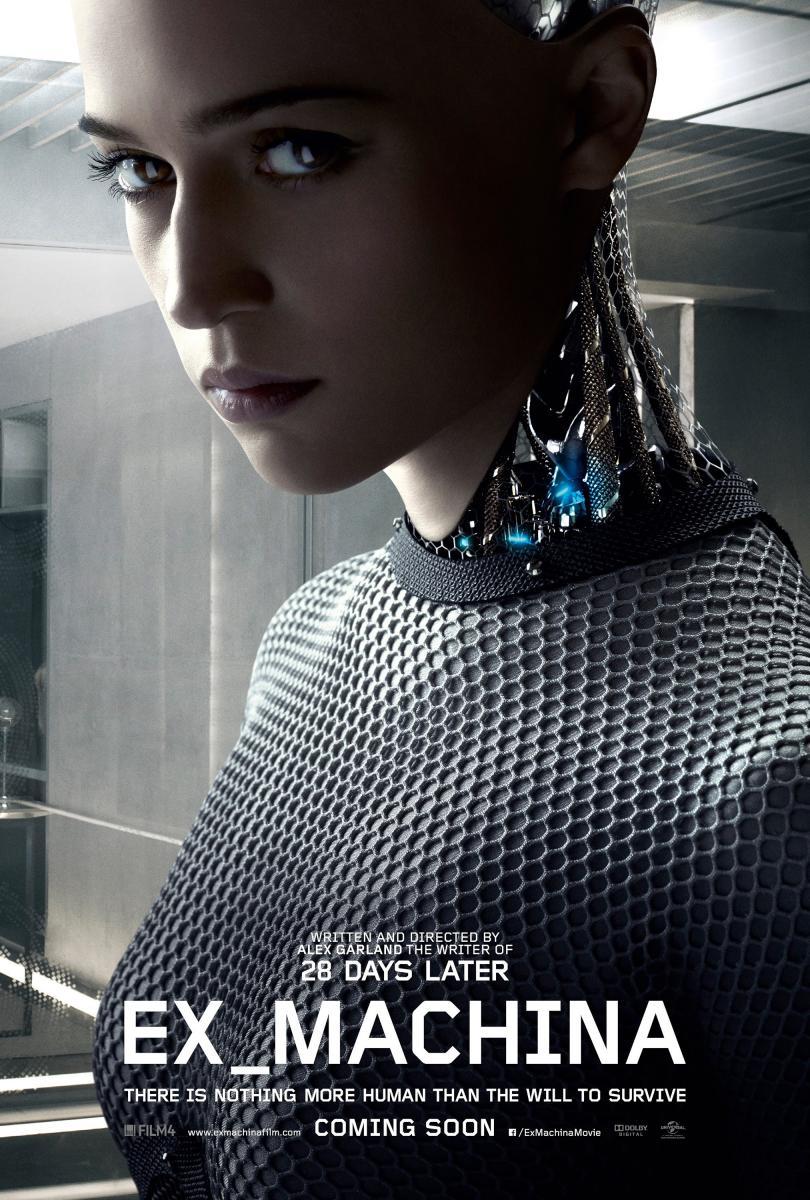

4. The Martian 5. Ex Machina

5. Ex Machina