written by (another) Christopher Miller

While my wife hunts for DVDs we haven’t already seen, I peruse Cherry Hill Video’s vast shredder1 shelves for interesting books. Because literary acclaim and commercial popularity are if not mutually exclusive then pretty antithetical, unlike over at Zehrs or Shoppers Drug Mart where it’s all overpriced, assembly-line pulp by publishing’s fistful of brand-name authors, here, for just five dollars, sparkle some real gems.2

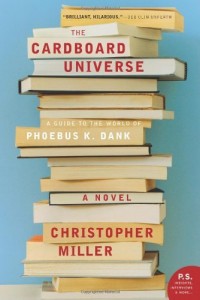

Like a defensive tackle hunting for offensive openings, I shift sideways past long shelves. So many covers vie for my attention, it’s mostly a crapshoot. Serendipitously for me my name is Christopher Miller or I’d probably never notice “The Cardboard Universe” by,Christopher Miller.3

Curious, I pick it up. Thick,a generous number of pages. Interesting cover,a stack of paperbacks. Its promising title is displayed more prominently than our name,another positive. No Kirkus “review”,always a huge plus. Some accolades of course, but no industry blurbs,ever since Nelson DeMille described Dan Brown’s “Digital Fortress” as “intelligent” I’ve been leery of these. On the back it says Miller teaches at Bennington College in Vermont. A random scan of some middle page reveals clean, intelligent, accessible prose,something about a canned pig-brains diet. But wait,it’s his second book. Darn. Ordinarily this is a show-stopper, second books being the ones publishers “help” authors rush out on the off chance the first book flies (as Miller’s “Sudden Noises from Inanimate Objects” certainly appears to have). So, again, lucky for me we have the same name.

Happily, I buy it (while my wife rents the next season of “Breaking Bad”). For the first few weeks all I do is drive around with it in my car. I show it to friends, coworkers, family members,lots of people. Everyone congratulates me and, until I come clean, exhibits newfound respect. Then, after I’ve finished using it as a novelty item (and given up on Updike’s “Couples”), I take it home and read it.

It’s in the form of an encyclopedic portrayal (complete with an index) of the sad and funny life and prodigious writings of science-fiction legend, Phoebus K. Dank, via an alphabetized compilation of reviews, essays and epistolary (warring) footnotes by two English professors, once close “friends” of his, and between whom no love is lost or opinion shared. The dominant of the two collaborators, William Boswell, who wrote his doctoral dissertation on Dank, acknowledges at the start that we are perhaps spared through his summarization of Dank’s considerable volume of texts having to wade ourselves through their copious “Dankian” prose to get at their genius. Owen Hirt, the other contributor, is scathing in all his remarks, both personal and literary, tending toward generalized mockery of the obese and obsessive author and his juvenile oeuvre, and to avoid, as though unworthy (or unread), abstract or example.

This threading of multiple narratives,Boswell and Hirt’s reviews; biographical accounts; footnotes inserted into each other’s entries,seems a risky technique. Readers develop preferences. My personal favorites are Boswell’s reviews of Dank’s work. It’s hard to summarize a novel that is itself so synoptic, and where so much stands out that it’s arbitrary to filter. Still, let me randomly and paraphrastically remember:

Dank’s novel about a brilliant writer who, in the course of writing the most intelligent book ever, incurs brain damage by nodding too vigorously during a philosophical discussion,only an IQ point or two, but enough that he can no longer understand what he has written.

Dank’s belief that when commenting on a writer’s work you should use the “poison sandwich” approach: say something nice; say what you really think; say something nice.

Dank’s novel in which he “forgets” about time zones and even hemispheres4 and has everyone on Earth waking up at exactly the same “time” one “morning” from the same dream, and when asked about his poetic license and intent here by well-meaning Boswell, horrified, breaks into a warehouse containing 8000 waiting-to-ship copies of his book and slips a note into each directing readers to skip the opening chapter.

Dank’s ability to write faster than he can type by using abbreviations for oft-repeated phrases like “bb” for “big-breasted” 5 but that lead to transcription errors like “robig-breasteders” for “robbers” in his published (and presumably unedited) manuscripts.

Dank’s obsession with literary recognition and acclaim that compel him, even as a popular author, to enter writing contests for children, though he never wins and only once short-lists. And to join a workshop for under-discovered writers who, despite his publishing successes, accept him on the sheer ignominy of his appearance, life and prose; a workshop whose “years of constructive criticism” have reduced the only other writer of talent in it to mediocrity.

Dank’s first novel, written when he was seventeen and said to have hit his literary stride and even apex, in which a dashing Captain admiring his manly uniformed reflection in his spaceship’s window is “suddenly” zapped by a laser.

Dank’s piece about an alternate universe in which everything is exactly the same as this universe except old, instead of young, people are sexy.

Dank’s piece about an alternate universe in which everything is exactly the same as this universe except women lust after men and even the fattest, least hygienic and most uncouth slob (like him) has no problem getting picked up in bars.

Dank’s piece about an alternate universe in which everything is exactly the same as this universe except instead of a writer named Phoebus K. Dank, there’s a prolific Phillip K. Dick.

Dank’s invention of a refrigerator that, instead of employing an energy-wasting compressor, pipes cold in from outside in winter.6

Dank’s murder-mystery about a serial killer who, instead of killing people he hates, kills the person seven below them in the phonebook, and who’s caught and executed just when he would have killed himself for listing, in the phonebook’s latest issue, seven below a cousin who’d wronged him.

Dank’s book about a man whose life and experiences in the course of writing this book must exactly mirror his own, forcing him in the interest of a more interesting book to do more interesting things in his life like flashing an elderly neighbor woman and writing another book (about a plague that makes everyone always say exactly what they’re thinking) that eventually becomes his most critically acclaimed novel.

Along with Dank’s life and writing as presented in his co-biographers’ droll reviews, accounts and commentaries, appears the story of his murder. This more conventional who-done-it (or maybe why-done-it) layer at first feels incidental, even superfluous to the novel’s purpose, like the grit around which a pearl forms. It’s asserted by Boswell from the get-go that Hirt did it, that this is why he’s hiding out of country e-mailing his entries. But as the story progresses, unhappy Boswell and vainglorious Hirt, each a failed (i.e. unpublished) writer in his own right, become more integral. In Hirt’s acrimony there seems to emerge a grudging respect. Something creepy lurks in Boswell’s fandom, his moping memoir so unencumbered by romantic, or even prurient, concerns as to render him asexual, his feelings for Dank nebulous,both protective and dependant,possessive. When Hirt begins to explore their relationship in one of his own accounts, Boswell truncates the entry and (until calming down after many pages) banishes him from the project.

Some books warrant abandonment, but not total disregard. And so some I’ve reviewed on the basis of a few chapters, others on just their covers. But that is not the case here. Boswell complains that Dank’s interest only in the book he’s writing is why his seven greatest novels are unpublished. Sometimes, as now, my involvement with the book I’m reading prohibits my withholding comment until the end. Luckily for readers of this review, right now I’m only about ¾ of the way though the book (into the T entries) and so can’t “spoil” (as I learned in Hosseini’s “Kite Runner” is a uniquely Western concept) the ending. Because I would.

Obviously I don’t mind a reviewer’s autobiographical intrusion into a review. There’s no such thing as objective criticism, no separating a book from its reader. Dank understood this better than either of his biographers. Consequently the relationship between author and reader, however speculative, too is inescapable. Hirt likens four-hundred-pound, near-invalid Dank’s attempts to market himself as a “daredevil” to Oz’s bellowing, “PAY NO ATTENTION TO THAT MAN STANDING BEHIND THE CURTAIN!”

But usually I dislike when a review drags the author extraneously into the fray. As though Wallace’s depression or Dick’s (and Dank’s) methamphetamine addiction or Findley’s sexual orientation or some romance author’s looks should make their work any less or more interesting or relevant. But, given this book’s scrutiny of the relationship between a writer’s life and his work, its thematic lens cannot but focus outward on its author. Dank’s fondness for near-parallel universes and split personalities and the book’s narration by characters divided only by Miller’s imagination, and even my solipsistic discovery of this book written by a namesake that tackles themes so dear to me as to not only plant ideas in but at times appear to lift them from my head, might make it the most relatable, therapeutic (also funniest) and daunting book I’ve ever read, and which even given Miller is the seventh most common surname in North America, is still just really, really weird is all. Like looking in the mirror and seeing someone else.

Epilogue

I’ve finished the book! Surprisingly for me, I’m not going to spoil the ending. Except maybe to say it’s not the sort of ending you can spoil. By which I mean I want to read it again.

Dank has yellow-highlighted in a book every single line but one that he takes exception to. In the “Meet the Author” afterword, titled “Dueling Theremins (Two Authors Disagree About Which One Imagined the Other),” Dank, from his sickbed, interviews Miller. But he must stick to the list of questions Miller has prepared for him. This little skit seems such a clever and natural integration and extension of the novel’s themes that I press harder on my yellow marker as I read. Though I hesitate where Miller answers with “Not yet.” Perhaps, as apt as it is, this is the line I’ll leave untouched, conspicuous for my omission.

And close with two quotes from the book. The first is Goethe: “Confronted by out-standing merit in another, there is no way of saving one’s ego except by love.” The second is Boswell’s: “I was never sure if he wanted my honest opinion or the sort of unconditional love that no sophisticated reader can give any writer.” Clearly, and luckily for my ego, I am not a sophisticated reader.

1 The assumption being that any quality-published paperback selling for 4.95$ must have been rescued from recycling.

2 Just because a book hasn’t sold well doesn’t mean it’s good. I bought Copeland’s “Girlfriend [Reader] in a Coma” and Gibson’s “Spook County” from these same shelves. Conversely a book’s enjoying huge commercial success doesn’t necessarily mean it’s bad†though no titles spring immediately to mind.

3 It’s humbling to go from fantasizing oneself the greatest writer of the twenty-first century (and possibly the third millennium) to discovering one is at very most the distant second-best living Christopher Miller.

4 Much the way Miller “forgets” that in Scrabble the “c” is worth not one but three points. So that Boswell’s having spelled “cat” with the “t” on a triple-letter square would have at very minimum resulted in a “grand total” of not “five” but seven points, leading me to wonder if this was a deliberate nod to Dank, or if Miller will now ask readers to skip page 286.

5 Both inspiring and also somehow forgiving this CM’s latest SF, “Causal Determinism and Free Will,” about “heroic” Philosopher Jack Stone, sent to Jupiter’s orbiting supercollider to save the universe from becoming caught in an experimental time loop, but who then for the entire story, and so presumably all eternity, can’t take his eyes off Jupiter-Ring Lock-Station Engineer Lieutenant-Commander Dolleen Payette’s enormous breasts.

6 This isn’t funny, just weird. Because that’s my invention (along with heated wiper-blades). I’ve been going on about it for years, and could probably call a dozen witnesses to corroborate.

Born in Switzerland, raised in Chicago, mostly Canadian now. ÂRestaurateur, software developer. Loves writing all genres,sci-fi to literary, horror to erotica. E.g.:ÂÂGanymede Dreams (a.k.a. Ganymede’s Song) ;ÂTake Our kids to Work Day;ÂA Hawk Circling the Wind ;ÂAdam and Eve Reading (almost) Quietly in the Bathroom

Born in Switzerland, raised in Chicago, mostly Canadian now. ÂRestaurateur, software developer. Loves writing all genres,sci-fi to literary, horror to erotica. E.g.:ÂÂGanymede Dreams (a.k.a. Ganymede’s Song) ;ÂTake Our kids to Work Day;ÂA Hawk Circling the Wind ;ÂAdam and Eve Reading (almost) Quietly in the Bathroom