interviewed by Carl Slaughter

Critters,Preditors & Editors, ReAnimus, Advent, Nyx, SFWA, snap books. Andrew Burt is a busy guy.

How is Critters different than/better than Scribophile, SF Novelist, Hatrack River Writer’s Workshop, and other critique workshops? Critters is the first workshop on the web. How did that come about?

Critters pre-dates the others you mention, but I don’t know if Critters is fundamentally better or different from any of the others. The more the better! The reason I started Critters was simply that there wasn’t any critique workshop on the web at the time. I was searching for one to join, actually, but, being the early days of the web, there just wasn’t one yet. Before I started Critters someone in a forum suggested we try emailing manuscripts back and forth, which I think half a dozen of us did… once. I submitted my critiques of the others’ manuscripts, but I think I was the only one. 🙂 So I figured, well, there’s this web thing, I’ll hang a shingle and see if anyone comes.

Over time other workshops popped in and out (often off-shoots of Critters, like Critique Circle), and some of them stuck, which is terrific. The more depth of critique an author can get the better for everyone. In terms of differences, Critters’ workload is modeled after a local, in-person workshop I belonged to, begun by the award-winning and awesome Ed Bryant (himself an alum of one of the early in-person workshops, Clarion). With a monthly meeting and a rough average of three manuscripts everyone critiqued, I implemented that as a “three critiques per four weeks” ratio in Critters. That’s seemed to work well. Doing critiques of others is probably half the benefit to one’s own writing, so it’s important to ensure people do critiques. (And in-depth ones; we have minimum critique length limits to encourage people to peer deeply into every story.)

One thing I do think that accounts for Critters success has been our “diplomacy policy,” whereby those reviewing a manuscript are urged to phrase their bad news in ways that have been shown to communicate, and avoid the phrasings that don’t communicate the message but do provoke negative reactions from the receiving author’s “lizard brain.” It’s usually as simple as saying, “The pace was too slow for my taste” instead of, “The pace is too slow”; this really seems to help.

Why is your workshop still free after so many years even though many workshops charge?

So this all started in 1995, back when the web was young, and there probably weren’t even enough people around for anyone to make money from a web site yet. I had also been running Nyx as a free service. Nyx was (and still is) free to use, funded by voluntary donations from those who like it. That seemed like the right model, so I started Critters as a free workshop as well. It made sense since the biggest “cost” if you will, is the effort that all the critiquers put into critiquing their fellow authors. Doing critiques of others is also of huge help to improving one’s own writing craft, so we do nudge people to participate, both in quantity and quality of in-depth critiques. You can’t buy that quality; and making people pay for it may even dilute it.

For our modest monetary needs, folks who like it donate as they feel the urge (with some low-key fund drive reminders; I don’t care for the in-your-face, we’re-holding-your-program-hostage-until-twenty-people-donate kind of public TV/radio fund drives, though I understand their necessity). I also added some Google ads to the site to fill in the gaps, though I figure most people run ad blockers and never see them. Critters doesn’t need a huge budget,it isn’t my full-time job and we have a few volunteers to help with questions and such,so we do fine.

You mentioned Nyx, the world’s first Internet Service Provider, which you founded in 1987. How did that come about? What made you want to start the first ISP?

I’d been on the “ARPAnet,” the network that later became the “Internet,” for many years, and was active in “Usenet,” the gigantic (for its day) distributed forum system. ARPAnet was only accessible to a small number of people at academic/research/government organizations. It was so cool, though… So when our department (I was a computer science professor at the University of Denver) was donated a behemoth of an old computer,a PDP 11/70, which filled an entire room,and we had nothing really to use it for, it sort of fell to me, because I was the only professor who even knew how to run it. I put the open source operating system known as “BSD Unix” on it (a precursor to today’s Linux), connected it to the university’s network going out to the world at large, hung some modems on it, and opened it up for the general public so everybody could access what was just being renamed “the Internet.”

I’m a fan of capitalism, but it doesn’t always work as well as it should. Before the public had any way to get on the Internet, I could see the writing on the wall that they would be getting on eventually, and I was dismayed at the thought of people being gouged to access all the cool Internet stuff. The culture of the net was/is something special, with (at the time) a high degree of altruism,people helping others just because it was a good thing to do. There were many large, corporate, non-Internet dialup modem services, like “Compuserve”, which were generally extremely expensive; and I could foresee them soon connecting to the net and charging people far too much. I thought it would be a good thing if that altrustic culture could get a leg up. The university itself is a non-profit, and lots of the content on the net was freely available, so it all made sense to open the net up to the public for free to show that it could be done. I also wanted to do what I could to continue the spirit of freedom of speech that permeated the non-public Internet, and avoid the heavy-handed moderation many of the other pay dialup systems showed. (I am a bit disappointed that so many forum sites have again returned to fairly heavy moderation, but perhaps this too shall pass.) So I wasn’t really thinking, “Hey, this will be the first Internet Service Provider for the public”; more it was, “Hey, people ought to be able to get on the net because it’s cool, and they can’t, and I can do something about that.” It didn’t even occur to me until later that I’d started the first ISP, when someone mentioned it. At the time I just figured it sounded like a good idea to get people onto the net. I suppose the experiment was a success! Nyx is still going, now as its own 501(c)3 non-profit corporation, still providing free email, web hosting, etc. and I’m glad to see that the general public now has a lot more choices, with costs of access that are still reasonable (indeed, often still free).

How do you keep such a massive site as Critters going with no full-time staff?

Minions! 🙂 In this case, software minions. I enjoy automating things, and seem to be reasonably good at it. (My computer science background is in networking, operating systems design, artificial intelligence, cybersecurity.) So, I’ve created a ton of custom software that handles 99% of what goes on with the site. I have a small number of volunteers who help answer questions, and I fix things when the minions make a mess.

You recently opened the workshop to nonfiction, mystery, and a slew of other genres and categories. Give us a list and tell us how this experiment is going.

Originally Critters was just science fiction, fantasy, and horror. That made sense in the early days, given that the people on the net were still largely geek types, who tend to like those genres more than others. I always had requests to broaden the list to include everything, so recently I did. We now have 16 workshops, covering every genre and every form of creative endeavor I could fit in. The list is:

Science Fiction/Fantasy/Horror Writing

Mainstream and Literary Fiction

Mystery, Thriller, and Adventure Writing

Non-Fiction Writing

Script, Screenplay, and Stageplay Writing

Kids Books

Comics, Graphic novels, Manga, etc.

Western Fiction Writing

Romance Writing

Adult Fiction

Video and Film

Music and Audio

Photography

Art, Painting, Drawing, etc.

Apps and Software

Website Design

The SF/F/H workshop is still by far the most active, since it’s best known for that. The others are growing, though I think I made a tactical mistake breaking them out into separate workshops at the outset. I should probably merge them back so there’s one large workshop everyone is in, and when I start getting calls to split off a genre then do that.

I had hopes that some of the non-writing workshop areas would catch hold, like video, music, art, web design, etc.; though that hasn’t largely been the case. There’s a long history of writers workshops, whereas there isn’t that depth of history in the others. But we keep trying things, alerting people they exist, so I’m ever the optimist.

Don’t you have to be an experienced author or editor to critique someone else’s story? If I can see how to improve your story, why can’t I see how to improve my own story, and vice versa?

Two parts to that…

1) They’re two different skills. I can tell that a computer won’t boot, and I may even be able to diagnose it as a particular blown chip, but that doesn’t necessarily mean I can pull out the board and solder in a new one. In some ways, critiquing a story is easier than writing: I can read it and keep tabs on whether I’m liking it or not. If not, I can, hopefully make some sort of guess what isn’t working for me. Too much boring text? Stilted dialog? Cardboard character? Critiquing is, at the heart of it, about explaining how you felt as you read that piece. All that requires is paying attention to your feelings as you read. But that doesn’t necessarily mean one knows how to fix it, and not break something else. (Add more detail about the character, but if not done well, may create stretches of boring text.) On the flip side, some authors may write well, but have little idea how they do it; or know how to fix what isn’t working. Hopefully as you critique a lot of other people’s work, you gain a sense of what works and what doesn’t, so you can avoid the pitfalls as you write your own stories. Both take practice, and I think both improve the other. Critiquing is often easier to get “right” to start with.

2) The Blind Spot. No matter how good you are at writing and/or critiquing, you can’t see your own work from an outsider’s point of view. You can’t have that “first time” experience, since that was when you put down the words in the first draft. You also know too much about the parts you didn’t write, which someone else won’t know. You know that the your human protagonist’s unnatural love of carrots is because he was raised by gladiatorial jester rabbits (which you never mention in the text); but the fresh eyes of a reader who only sees the text can ask the question, What the heck is it with the carrots?

Isn’t it dangerous to post a story for multitudes of strangers to see? What’s to stop someone from plagiarizing a story? And although manuscripts are copyrighted, ideas are not, so what’s to stop someone from stealing my premise?

Actual plagiarism is extremely rare (I can’t think of any actual cases in Critters in all the years and tens of thousands of manuscripts). I suppose it’s because (1) people know they shouldn’t do that; (2) the penalties are stiff if you do and you get caught; (3) the story in Critters is the unfinished product,why should someone want to steal a half-baked cake out of the oven?

As for ideas, right, they aren’t copyrighted. However, they’re not what make a story uniquely yours. Ideas are a dime a dozen. Most ideas have already been done over and over. (A spunky group of rebels fights against an entrenched empire… Is that Star Wars, the American Revolution, Asimov’s Foundation, Hunger Games, V for Vendetta, or… or… or…?) Even if someone has a truly unique idea, (1) without good writing it won’t matter, and (2) several authors could run with the same idea and make completely different stories.

So, nawww, nothing to worry about.

Is one week really enough time to read, evaluate, and comment on a story? What if I critique regularly for several members and 2 or 3 post a story at the same time?

Interesting question! Nobody has ever actually asked for more time to critique a short story. (Novels have their own slower-paced program.) I think it’s enough in that the story itself rarely takes more than a few minutes to read, and then it’s a matter of writing up what you thought about it. I’d say for a typical story that takes me maybe an hour tops, and I don’t think I’m particularly fast at it. I may let the story percolate in my brain a few days, but there seems to be time by the seventh day to get the thoughts written down. The emphasis is really on how you felt about the story; what parts worked and what didn’t; not so much about line by line edits. It’s then a matter of relating your feelings.

As for regular authors, I don’t know if I would encourage that. To my mind, it’s more helpful to both the author and critiquer’s own writing to critique a wide variety, not a “stable” of authors.

How many critiques might a story receive on Critters?

Historically the average has been 15. That varies quite a bit based on a bunch of factors (length of your story, for example; and middle chapters of novels have a hard time, which is why there’s a program to critique entire novels).

What kind of publication success rate do Critters members have?

It’s hard to measure precisely, but I once did a study and it came out that members of Critters were ten times more likely to make professional sales than non-Critters. Of course, it could simply be that the more motivated writers have joined! I can’t attribute cause and effect.

Have you had a lot of pro writers participate? Any Hugo, Nebula, or Campbell winners/nominees? Any Writers of the Future winners? Any members who participated in the Clarion or Odyssey workshops? A lot of SFWA members?

Lots and lots… though I really don’t keep a database of them. Pro authors tend to be busier, but many like to “pay it forward” by helping new authors. I’ve noted in many years that around a third of nominees for the Hugo or Nebula awards are Critterfolk. Probably our most decorated author is Ken Liu, who’s won a bunch of Hugos and Nebulas.

You’ve proposed that keeping an ebook online indefinitely can eventually bring in as much sales or more as putting a paper version in the bookstore because the paper version is pulled in a few months. But suppose ebook formatting evolves and the old formatting is no longer compatible with the new readers or new software?

There is already software that can convert between formats. Calibre is one example. Formats like EPUB are particularly easy to convert in the future, since they are basically a “.zip” file with HTML files inside, which is human readable text that software can easily operate on. Very easy to convert to some other format. Even if there were some difficult file format, since the text has to be visible to the human eye to read it, there will always be a way to convert it, even if it’s taking photos of the words and converting back to text (like ReAnimus Press does for out of print books). It’s highly unlikely anybody buying an ebook today will be unable to read it in the future.

Selling ebooks requires using PayPal or a credit card. Doesn’t the author have to pay a fee for these payment services? If a customer buys only one of your books, you still have to pay that fee. If 10 people, 100 people, 1000 people buy only one book each from you, you’ve paid that fee many times. How is that going to work out for you as a business model considering one of the chief advantages of ebooks is reduced price?

First off, the lions share of ebook sales today are through Amazon. They take their cut (about 30%), and that’s that. That includes the credit card fees. Many authors seem to be okay with that 30% figure. Amazon provides the infrastructure (including the payment processing as well as the web site to display and host the books), they provide a reasonably priced ereader device, they provide a sort of central market square where a lot of people congregate,which includes providing a sense of trust, which shouldn’t be overlooked for it’s value,and they provide marketing (“If you liked that perhaps you’ll like this”).

But even for direct sales the processing fees aren’t particularly painful. Paypal for example is around 3% plus 30 cents, or, with their “micropayments” account, 5% plus 5 cents. Not trivial, but for a $5.99 ebook, 35 cents to Paypal leaves $5.64 to the author. That’s a lot more per sale than you’d earn if you published through Random House.

I also imagine, as time goes on, we’ll have even better forms of payment. There are a number of concepts and startups out there to make payments even easier and cheaper. While I think bitcoins are too volatile as an investment vehicle and prone to security issues, they do have one potentially interesting use: An “instant” way to send money, even between different currencies. That is, if I wanted to send $10 to someone in Upper Nowheria, where they use Quatloos as currency, I could use a service where I send in $10, the service converts it to bitcoins at the current exchange rate of that moment, sends the bitcoins to the person in Upper Nowheria, converts to Quatloos, all within a microscopic fraction of a second, and with a very low exchange fee (a fraction of a percent, depending on bitcoin exchange fees). Currency exchanges often cost 5-10%, so this could cut that way down. Or some other virtual currency or system could serve the same function. Someone out of the US made a large donation to Nyx recently using Transferwise.com, which, including foreign currency exchange fees, was at 0.5% in total fees. The tendency is toward zero exchange and transmission cost.

Don’t ebooks make piracy easier?

Yes, but. First, you’d have to determine what percent of pirated copies would have actually resulted in a sale if piracy were impossible. I did a survey on that once, and it came out that most people simply wouldn’t have paid. There were very few truly lost sales. Most pirates just wouldn’t have paid, for a variety of reasons. (They may not have the money, they may not have lived in a country where they even could have easily paid if they wanted to, they may not have felt the book was really worth X dollars, etc.)

Second, you have to figure out if there’s any marketing value. I view them much like used books. Authors make no money from used book sales or books passed along to friends, etc., but readers who receive the free/low-cost used book may turn into fans who buy the author’s other books.

Third, copy protection (DRM , Digital Rights Management) software is almost always intrusive and annoying. In order to prevent a few pirated copies, it greatly limits and greatly annoys legal users. DRM can also get outdated, rendering the protected thing inaccessible. (Has happened to me.) As a legitimate user, I hate copy protection.

Many publishers have decided it’s best for their bottom lines to abandon copy protection.

You’ve been a strong advocate of ebooks. You’ve gone so far as to predict the extinction of publishers. Can ebook self-publishing replace the massive editorial and marketing apparatus at the disposal of publishers?

I think ebooks are wonderful. I’ve been an ebook reading person since the early 2000s, when I started reading on the old Blackberry phone I had. I would write to the authors of books I wanted to read to request copies of their manuscript (it helped that they were fellow SFWA members and often friends). I also think we’ve just scratched the surface of digital reading devices. (For example, if there were an inexpensive device that looked and felt just like a book, except every page was digital,digital ink on real paper, or digital paper,you would hold in your hand the same thing as a paper book, except it would be an e-reader. At that point, you have all the “features” of a print book, plus all the benefits of digital. We may phase out paper sooner than that, but it represents a sort of upper bound on when we’ll no longer read paper where the words on the page can’t change.)

So publishers have a problem. If they don’t remain relevant, and bring something unique to the table, they will fade away just like blacksmiths and buggy whip makers.

Anyone can now do (or hire someone to do) the traditional tasks that publishers have done to put together a book (editing, cover art, layout, etc.),and do them in such a way that the author earns a lot more of the proceeds from the sales.

I think one key role left for the large publishers is marketing. Unfortunately, publishers don’t do a lot of that for most books. To some extent, getting paper copies of a book placed on tens of thousands of bookstore shelves counts as marketing. (Readers can’t buy what they never see.) Having the economies of scale to print thousands of copies of a book inexpensively is still one of the competitive advantages that big publishers have. (Which dwindles the more people read digitally.) But if that’s substantially all the publisher does in marketing a particular book that an author can’t do themselves, then it becomes questionable if that’s worth the huge cut of the profits that they take. It’s not unreasonable to say a self-published author could sell 5% as many copies of a book and make the same money.

The question is whether the self-published author can sell that number of copies. The average self-published book sells around 100 copies over all. That’s not much. However, the flip side is that same book may simply never sell to any publisher at all, so that’s 100 compared to 0.

If an author is incredibly good at marketing, and is able to do or pay for the production work, they can probably make more money self-publishing. If not, using a publisher may make more sense.

Another factor in the publishers favor is that they put up the money for the production/distribution costs, taking on the financial risk they might lose money; and they pay the author an advance up front. Those may be more important to a given author than overall earnings.

However, the other big hiccup is in the duration: Large publishers may take the rights for the duration of copyright,that’s the life of the author plus 70 years(!). During which a publisher may not do much marketing after the initial push. Not to mention, a lot can change in that length of time. Even a slow trickle of sales could add up. (Let me emphasize that: If an author is, say, 30, and lives to be 90, the publisher will collect the lion’s share of the royalties for 130 years.)

Full disclosure: In addition to my Critters hat, I’m a publisher; I run ReAnimus Press. We specialize in digitizing out of print books for authors, though we also publish some new releases. We do our best in marketing, and we typically work with authors who for whatever reason don’t want to do the production work themselves. (That said, we pay the highest royalty rates of any publisher I’m aware of. We try to do right by authors.)

Bottom line, an author has to carefully evaluate what a publisher brings to the table, today and for possibly a hundred or more years into the future. It’s a hard decision to make.

As a former vice president and one time presidential candidate, do you agree with Mike Resnick’s assessment of SFWA?

“The broader the membership, the less clout is has. When I joined SFWA more than 40 years ago, we were a lean fighting machine, boycotting publishers and making it stick, publicizing bad contracts and bad agents, auditing publishers and actually winning hundreds of thousands of dollars in unreported royalties for our members. But we were all full-time writers. Then we stopped insisting on requalification every 3 years, and our membership went from maybe 150 real writers to 1,500, of which more than 1,300 are not full-time writers and do not have the same professional interests as the full-timers. As a result, we are now pretty much powerless to act as an organization whose first duty is to protect its membership, because our membership no longer consists of people who write for a living. We have not conducted an audit in 30 years; we have not publicly evaluated a contract in 25 years; we have not publicly evaluated agents in 25 years; we do not report the average wait time , above and beyond what is contracted for , for a publisher to pay the signature advance, the delivery payment, or to issue the royalty statement; and we have totally disbanded our piracy committee. All this is a direct result of becoming a less professional organization with every passing year and more of a social club, so you’ll forgive me if I think that lowering the standard even more will be anything but deleterious.”

So: Yes, I agree with what Mike says about SFWA having become less effective. I mostly disagree that the cause of this drop in effectiveness has anything to do with who the members are. I think the lack of effectiveness stems mostly from a lack of focus on the part of the leadership. Or a focus on things that don’t necessarily accomplish anything: Such as focusing ad nauseum on rewriting the bylaws and shuffling the furniture around. (The presidents have generally been authors who make a living from their writing, and they’re the ones who guide the ship, so I don’t really think the fault is lack of full-time writers making the decisions.) I think SFWA could easily do all those things it did in the past to help writers,and with 1500 members get more respect from, say, Congress, than if it had 150 members. Not to mention the much larger budget and surpluses in the bank. I’m constantly optimistic that at any moment SFWA could re-awaken as a real force for writers. There are tons of things it could do to help writers, if the leadership wanted to steer that direction.

How did you become the editor of Preditors and Editors and what can we expect with you at the helm?

Preditors and Editors fell into my lap mainly because I had worked with P&E’s founder, Dave Kuzminski, since the late 90’s running P&E’s annual Readers Poll. So as time rolled around to start the poll, I emailed Dave to discuss various things. And heard nothing. I kept trying, eventually getting in contact with his wife and learning that Dave had died very suddenly. They couldn’t even access the site, nor had any idea how to do his P&E magic (not being authors), they turned it over to me. My hope is to keep running P&E the way Dave did, helping authors avoid scams, though he left mighty big shoes to fill. We have added a general guide to avoiding scams that encapsulates advice about a lot of what we see.

You started ReAnimus Press. Why? What do you publish, and how’s it going?

ReAnimus is going great. We have about 200 titles released or in the pipeline, almost all from well known and award-winning authors. We have a couple dozen from Ben Bova (including his rare first novel, paper copies of which were going for $500 apiece), over 20 from Norman Spinrad, everything by SFWA founder and Grand Master Damon Knight, and a lot more. We just got the rights to do the ebook of edition of DEAR AMERICA: LETTERS HOME FROM VIETNAM, which is a bestselling book and basis for the Emmy award-winning documentary (letters read by Robert DeNiro, Robert Downey Jr., Robin Williams…). So it’s been an amazing ride so far.

I started ReAnimus because I had these huge shelves full of books, most now out of print, and I wished they were all still available for readers, either as ebooks or in print. I had the technical background to do something about it and some author friends asked me for help getting their backlist back out there… so it all just came together. We now have a pretty sophisticated artificial intelligence system to fix the huge number of errors that result from scanning.

While we mostly only publish established authors (where, to be honest, the risk of losing money is a lot less), we also offer the digitizing and layout services for folks who want to do their own thing.

It’s a real blast, and I’m honored that we’ve been able to bring some great books back into readers’ hands.

How did you acquire the celebrated Advent Publishers and what can we expect with you at the helm?

Advent Publishers is another story of reanimating books that might otherwise be lost. Because ReAnimus Press specializes in bringing out of print books back to life, one of our authors put me in touch with the publisher of Advent. They had a bunch of books still in print, but no digital files to make ebook editions. We got to talking, and it became evident that the best solution was just for ReAnimus to acquire Advent.

We’re thrilled, since Advent is a Hugo Award winning publisher that’s been around since the 1950s, having published the biggest names in SF (Heinlein, Blish, E.E. “Doc” Smith, et al.). Our plans are to create new ebook and print editions of their catalog, help sell the existing warehouse full of print titles, and, to be sure, acquire new titles that fit in with Advent’s illustrious family.

How’s your own writing going? Anything new?

Yes, I recently finished a novel that I’m shopping around, Termination of Species. The biggest problem I have,assuming some major publisher actually wanted it,is the same dilemma as I outlined above: Which way would I be happier with, locking up my rights for a loooong time with a major publisher who doesn’t pay a very high royalty rate, or the potential but much higher risk of self-publishing it? I’m really gridlocked on that! I’m working on my third novel, and making good progress.

What other projects are you involved in to facilitate activity within the science fiction community, what is their purpose, how do they function, and where do we access them.

Well, I do try to sleep sometimes. But I toss out various tools for writers, blog about stuff of interest to readers and writers, and fill in cracks of time with other sorts of things that are listed at www.aburt.com.

Within ReAnimus Press, we’re developing and patenting a way to easily sell ebooks through bookstores, called “snap books”,the name coming from the incarnation where there’s a physical, book-like-object sitting on a bookstore shelf, with the book’s cover art and description on it, and the reader snaps a picture of the QR code to buy, download the book, and put the display box back on the shelf for the next person. Has a huge number of applications.

It came into being because I’ve long wanted to find a way for physical bookstores to sell ebooks. I love the experience of browsing in a bookstore. But they’re out of a lot of titles, they don’t have ebooks on the shelf, etc. So the idea hit me how to solve that, and we’re rolling it out. So far people love the idea. (Gratuitous plug: If anyone reading this works in a bookstore, or knows people who do, or, for that matter, any place that could sell physical things, like a coffee shop, convention dealers room, etc.,drop me a line!)

All in all, I’m having a blast! Thanks for choosing me for an interview!

Carl Slaughter is a man of the world. For the last decade, he has traveled the globe as an ESL teacher in 17 countries on 3 continents, collecting souvenir paintings from China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, and Egypt, as well as dresses from Egypt, and masks from Kenya, along the way. He spends a ridiculous amount of time and an alarming amount of money in bookstores. He has a large ESL book review website, an exhaustive FAQ about teaching English in China, and a collection of 75 English language newspapers from 15 countries.

Carl Slaughter is a man of the world. For the last decade, he has traveled the globe as an ESL teacher in 17 countries on 3 continents, collecting souvenir paintings from China, Korea, Thailand, Vietnam, and Egypt, as well as dresses from Egypt, and masks from Kenya, along the way. He spends a ridiculous amount of time and an alarming amount of money in bookstores. He has a large ESL book review website, an exhaustive FAQ about teaching English in China, and a collection of 75 English language newspapers from 15 countries.

CS: At the beginning of the series, McKenzie is a Nancy Drew type, using her gift to analyze the scenes where fae transported. By the end of the series, she has learned how to wield a sword and uses it in battle. So she’s become a sort of warrior princess type. Why the transformation?

CS: At the beginning of the series, McKenzie is a Nancy Drew type, using her gift to analyze the scenes where fae transported. By the end of the series, she has learned how to wield a sword and uses it in battle. So she’s become a sort of warrior princess type. Why the transformation?

CARL SLAUGHTER: You’re one of the pioneers of podcasting.

CARL SLAUGHTER: You’re one of the pioneers of podcasting.  CARL SLAUGHTER: Who is the Princess Scientist, what are the science topics, and how mad is the science?

CARL SLAUGHTER: Who is the Princess Scientist, what are the science topics, and how mad is the science? CARL SLAUGHTER: Suppose someone wanted to launch a podcast. How much money would they need to raise? What would they need in the way of recording equipment and web resources? What would they need in terms of personnel?

CARL SLAUGHTER: Suppose someone wanted to launch a podcast. How much money would they need to raise? What would they need in the way of recording equipment and web resources? What would they need in terms of personnel?

LAURA RESNICK: An editor once cited Barbara Michaels aka Elizabeth Peters to me as an example of a writer whose career was held back for years by bad covers. Peters died last year (peacefully at home, at the age of 85) after a career which included many New York Times bestselling novels. But that success came some 20 years and many well-reviewed books into her career, and there was a noticeable shift in packaging that accompanied her well-deserved success. For years, publishers were giving her muddy, generic covers that conveyed nothing of the tone of her books, and she developed her audience strictly on her own merits via word-of-mouth, with no help at all from her dreadful packaging. Then if you look at the packaging she started getting around the mid-1990s, you can see a definite shift in quality of the covers, which accompanied her rising sales. In particular, the eventual packaging of her Amelia Peabody series (the early books, poorly packaged, were also repackaged with the new look) was a winner, and the series was commercially very successful for years (she was working on another Amelia Peabody book when she died).

LAURA RESNICK: An editor once cited Barbara Michaels aka Elizabeth Peters to me as an example of a writer whose career was held back for years by bad covers. Peters died last year (peacefully at home, at the age of 85) after a career which included many New York Times bestselling novels. But that success came some 20 years and many well-reviewed books into her career, and there was a noticeable shift in packaging that accompanied her well-deserved success. For years, publishers were giving her muddy, generic covers that conveyed nothing of the tone of her books, and she developed her audience strictly on her own merits via word-of-mouth, with no help at all from her dreadful packaging. Then if you look at the packaging she started getting around the mid-1990s, you can see a definite shift in quality of the covers, which accompanied her rising sales. In particular, the eventual packaging of her Amelia Peabody series (the early books, poorly packaged, were also repackaged with the new look) was a winner, and the series was commercially very successful for years (she was working on another Amelia Peabody book when she died). LAURA: At large publishing conglomerates (ex. Hachette, HarperCollins, Penguin Random House, MacMillan, and Simon & Schuster), too often the people making decisions about packaging are unfamiliar with the book or the author’s work,and therefore also unfamiliar with the author’s audience, who are the people the cover needs to attract. I have even been told anecdotes by wearily amused art directors about book covers being directed by senior people in the corporate hierarchy who don’t read books and who have no art or design background whatsoever, but who, for one reason or another, want cover control. To give just one example of how truly absurd the process can get, one art director at a major house told me that for a year or two, most of that company’s major releases had red covers because the Chief Financial Officer’s girlfriend liked red, and he wanted to make her happy.

LAURA: At large publishing conglomerates (ex. Hachette, HarperCollins, Penguin Random House, MacMillan, and Simon & Schuster), too often the people making decisions about packaging are unfamiliar with the book or the author’s work,and therefore also unfamiliar with the author’s audience, who are the people the cover needs to attract. I have even been told anecdotes by wearily amused art directors about book covers being directed by senior people in the corporate hierarchy who don’t read books and who have no art or design background whatsoever, but who, for one reason or another, want cover control. To give just one example of how truly absurd the process can get, one art director at a major house told me that for a year or two, most of that company’s major releases had red covers because the Chief Financial Officer’s girlfriend liked red, and he wanted to make her happy. LR: Well, “marketing” is a broad term, involving a lot of areas unrelated to the book cover. It is, in essence, the question of how to get lots of people who are likely to enjoy the book to pick it up in the first place.

LR: Well, “marketing” is a broad term, involving a lot of areas unrelated to the book cover. It is, in essence, the question of how to get lots of people who are likely to enjoy the book to pick it up in the first place. LR: Not alienating relationships at the publishing house is a matter of professionalism in all things, not just covers. And, frankly, I’ve worked with a couple of publishers in the past which are so unprofessional and so contemptuous of authors that there’s really no way to get anything done without alienating them. (Also, in retrospect, I don’t regret the instances where I alienated publishing staff in order to protect my books. I regret the few instances where I foolishly backed off on protecting my books in order to try to preserve relationships with publishers; this turned out to be the wrong decision in every instance. When a book is handled badly, sales suffer, and so the relationship is destroyed anyhow,because publishers publish for money, not love, friendship, loyalty, or honor.)

LR: Not alienating relationships at the publishing house is a matter of professionalism in all things, not just covers. And, frankly, I’ve worked with a couple of publishers in the past which are so unprofessional and so contemptuous of authors that there’s really no way to get anything done without alienating them. (Also, in retrospect, I don’t regret the instances where I alienated publishing staff in order to protect my books. I regret the few instances where I foolishly backed off on protecting my books in order to try to preserve relationships with publishers; this turned out to be the wrong decision in every instance. When a book is handled badly, sales suffer, and so the relationship is destroyed anyhow,because publishers publish for money, not love, friendship, loyalty, or honor.) LR: Authors are doing this in the self-publishing world,and in many cases, very effectively and successfully. In the traditional publishing world, though, you don’t want to do this. One, your publisher won’t go along with it; two, why on earth would you sign a contract that funnels the majority of the income to a publisher if they aren’t going to pay for the packaging? If you want to do the packaging yourself, then self-publish. (For some examples of great self-published covers, check out some awards sites for “best of” indie and self-published cover art.)

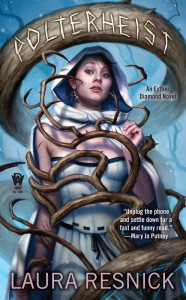

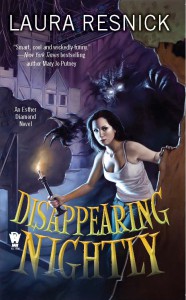

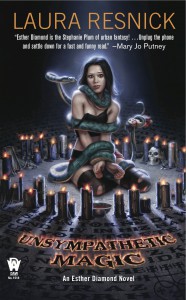

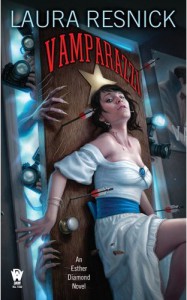

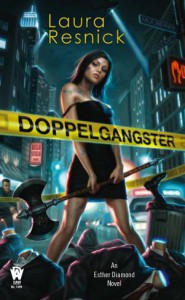

LR: Authors are doing this in the self-publishing world,and in many cases, very effectively and successfully. In the traditional publishing world, though, you don’t want to do this. One, your publisher won’t go along with it; two, why on earth would you sign a contract that funnels the majority of the income to a publisher if they aren’t going to pay for the packaging? If you want to do the packaging yourself, then self-publish. (For some examples of great self-published covers, check out some awards sites for “best of” indie and self-published cover art.) LR: The Esther Diamond covers are illustrated by the brilliant Dan Dos Santos. He’s a Chesley Award winner, a five-time Hugo Award nominee, and has won or been nominated for numerous other awards for his art. He’s also prolific, so you’ve probably seen his art on numerous other book covers.

LR: The Esther Diamond covers are illustrated by the brilliant Dan Dos Santos. He’s a Chesley Award winner, a five-time Hugo Award nominee, and has won or been nominated for numerous other awards for his art. He’s also prolific, so you’ve probably seen his art on numerous other book covers. LR: The market and the book/publishing world have changed a great deal during the years I’ve been writing professionally, yet I find that the two most common mistakes that aspiring writers make have not changed at all: not writing enough and not educating themselves about the business. And so my advice hasn’t changed, either. It’s still:

LR: The market and the book/publishing world have changed a great deal during the years I’ve been writing professionally, yet I find that the two most common mistakes that aspiring writers make have not changed at all: not writing enough and not educating themselves about the business. And so my advice hasn’t changed, either. It’s still:

Is there such a thing as style rules (see below) or is that conventional wisdom / dogmatism? Shouldn’t the story determine the style rather than vice versa? “Yeah, but famous author X breaks the rules all the time and the editors don’t challenge him on it.”

Is there such a thing as style rules (see below) or is that conventional wisdom / dogmatism? Shouldn’t the story determine the style rather than vice versa? “Yeah, but famous author X breaks the rules all the time and the editors don’t challenge him on it.” and developing characters and reinforcing themes?

and developing characters and reinforcing themes?

To ebook or not to ebook, that is the question.

To ebook or not to ebook, that is the question. True or false: The system is rigged against the rookie and in favor of the veteran.

True or false: The system is rigged against the rookie and in favor of the veteran. You described Gardner Dozois as a manuscript doctor genius. What exactly did he do to fix a manuscript?

You described Gardner Dozois as a manuscript doctor genius. What exactly did he do to fix a manuscript?