edited by David Steffen

They hold each other in the shallow cool of an August night, two among many in a backyard arced in string-lights, wrapped up in the music and the celebratory ethereality of a wedding. They dance together like it’s theirs, in a moment that is just itself and what they are within it.

* * *

When they woke it was in what little pocket warmth they’d accumulated between their bodies in the night, clinging together in a sleeping bag as if without the other they would forget how to breathe, or why. When Nash cracked his eyes open to take in this reality it was to Vicky watching him, her face as beautiful as everything behind it, a moment of naked love in which they both wished that they could remain lying here like this, frozen in stasis. Neither needed to say it.

But time moved on. Inexorable, mechanical as a wave in the ocean, as the dissolve of light into dark. They knew it was time to go when Vicky mumbled that he needed to brush his teeth, and Nash said that she’d had too much to drink last night.

“Well, how else am I going to sleep through this?” she snapped, pulling away from him.

“You’re the one who wants to cram us into this one bag,” Nash said. “Not my fault that you can smell my breath—”

“Stop.”

They took a moment to recollect, looking first at the tent walls, then the travel bags at their feet.

“I guess it’s time to go,” Vicky said.

They emerged into a winter in stasis, here in this relic world. The ground cold and hard-packed, overhung by bare trees. Gray sky.

“I’ll get the tent down,” Nash said.

“I’ll pack up,” Vicky said. This was how they handled the moments when the future came too close, advancing behind the fiery orange and red tendrils of the wave that separated it from this world of the past. It brought preliminary effects: budding trees, shoots of green grass, mild warmth that whispered with the summer.

For living things, its effects were the beginning of the state that they would be in, once the time-wave passed over them and brought them days? years? into the future. Like foreshocks to a temporal earthquake, and what waited on the other side?

For Vicky and Nash, it meant that they started fighting. Building up walls and nurturing resentments. Making plans to leave. Once they outran those foreshocks, got beyond the effects, regret filled them and they made up.

Which meant that whatever era of their lives existed beyond the wave, in the future, didn’t involve them together.

And so they ran, the last of the living on this side of time, defying the mechanical, unceasing advance of loss—struggling to stay together, and in love.

* * *

Neither could remember how long they’d been here. Living in this world of the past meant that one’s perception simplified to a moment-by-moment basis, shedding the artificial measurements of hours and days. But here, in this unceasing end? Anything beyond the moment was hard to understand. A freedom in that, at first.

But now, when they woke from scant hours of sleep, suffering those preliminary effects, bitterness and resentment led each to privately wonder a terrible option… so they just went through the motions. Pack up. Get in the car. Eat breakfast on the road. Start talking when the shame from holding those resentments built, then gave way.

Yet there was only so much land left. The geography had gone flat, and though they didn’t know what the road signs for exits and dead towns meant, they knew that these were coastal plains; soon they would smell the ocean.

“We’ll find a boat,” Nash said.

Vicky took his hand. “I don’t know how to steer one. Do you?”

“No.”

She ran her thumb over the back of his hand. “We’ll figure it out, then.”

But they both knew that they couldn’t get a boat running, not before the wave reached them. Before the future did.

* * *

Vicky missed her family. Nash his friends, because they were more like family to him. She couldn’t help wishing that she was back home, speeding down the highway as the sun set over cornfields and a thunderstorm rolled in across the miles. He wanted to stand out on the porch after the rain left and birdsong returned, and the fresh sunlight glittered over puddles in the driveway.

They’d had to leave their dog behind. Neither one could remember him fully, but when they started talking about him it all came back. Who was with him now? If the wave passed over them, would he still be there, back home, waiting for whichever one took him?

Time had nearly overrun them once before, when they’d crossed the mountains with those crooked switchbacks inching them along. But the wave passed over everything in a line, unstoppable—it had come so close that the sky lit aflame with orange and red aurora streaks whipping the sky and land, while phantom leaves eased into being and cars like ghosts materialized. Their screaming match had left them in tears. Vicky had been driving, and finally shouted, “If I’m that bad, then why don’t I just hit the fucking brakes?” And Nash spat, “Because you’re scared.”

That night, lying in the sleeping bag, far enough away from the wave to apologize again and again and believe it, Nash whispered, “I’m scared, too.”

“Is that why we’re still doing this?”

He brushed her bangs from her eyes. “Because we love each other, too.”

“But are we running for love? Or to get away from what’s on the other side?” She paused, then answered her own question. “Both, I guess.”

“Is that…” Nash swallowed. “Is that any reason to stay here? In the past?”

Vicky blinked back more tears—why did she cry so much, being with him? “I don’t know. Isn’t that… most relationships? Sometimes it’s love, sometimes it’s because that’s what we know and we stay because it’s less scary than leaving?”

“I don’t want that to be why.”

“Me, neither.” She kissed him, held him. And they both kept silent the same fear they harbored: What happened when they reached the ocean?

* * *

When they passed the first road sign that announced the distance to the beach, Nash asked, “What’s your favorite memory of us?”

Vicky gave a strained, but real smile. She said, “When we ran off to Seattle.”

“Yeah?”

“Yeah. Just… running off with this wonderful guy. But the moment itself, it was when we were sitting on the patio at that restaurant that looked out over the water. Remember that place?”

“The one with the trout?”

Vicky laughed. “You ordered it but didn’t know they serve the entire fish. The look on your face when they brought it out was just so… real. And cute.”

“Never ordering trout again.”

“But we were just sitting there, couldn’t have been more than half an hour. The sun was out, and all the people were walking by and I looked over at you and you were doing the same thing I was. Just taking in the world. And that was it. That was all I needed, was being in a new city, with you. You were the only thing that was solid for me, in the middle of all this strange newness. Like an anchor.”

Nash squeezed her hand.

“What about you?” she asked.

“It’s dumb.”

“No it’s not. What is it?”

He smiled, keeping his eyes on the road. “Remember when we went to the Fair last year?”

Vicky rolled her eyes. “Not really. Not after the fourth margarita… that night is your favorite? I was blackout drunk.”

“Okay, not that part of it. But it was… I don’t know, when I got you to the car, pretty much carrying you and you were singing ‘Don’t Stop Believing.’”

Vicky groaned and he laughed, but not in a mean way.

“And I got you into the car and drove us back, and you were mumbling about the pigs in the petting zoo, how you wanted one as a pet—”

“I still do.”

“But then you fell asleep, pressed up against the window.” He paused, swallowed through the hitch in his throat. “You needed me right then and I was there. Helping you, I guess… being your man. Just carrying you home.”

She watched him watching the road. Then leaned over the console and into him as best she could, face buried into his neck while he held an arm around her with the other on the steering wheel, wanting more than anything to pull over and hold her back. Eventually, she started to wish he’d changed into a different shirt, but he was always doing that, just picking up whatever piece of clothing was in sight, even off the floor. And he wanted her to take over more of the driving, he was tired and sore and he always had to take the lead.

They separated, back to their sides of the car.

* * *

But there was another memory. Profound for both of them, and maybe if they had mentioned it to each other it would have displaced the patio in a new city, and the late-night drive carrying her home, because for it to be held so deeply by both of them would have made it more than their independent moments. But they hadn’t told each other, hadn’t had the time.

Two of their friends were married in a backyard on an evening in August—the two who had connected Vicky and Nash in the first place—so they were both in the wedding party, had even walked down the aisle together in a bridesmaid dress and groomsman tux like precedents to a different dress and tux. After the service it was dinner and cake and drinks under tents in the backyard, speeches, and as the sun sank the DJ started the music.

Neither of them remembered the night with much coherency, thanks to the open bar. But the clearest moment wasn’t the ceremony, the speeches, any of that.

It was when they’d been dancing, alongside all these friends and strangers, under string-lights with the grass cushioning their sore feet, the music meaning little more than what moved their bodies together and held their eyes in lockstep. A moment—just a light on a string of them, but it glowed brighter than the others. It ended and yet it never ended, swelling into a presence real and powerful and continuing on as separate memories to exist in shared pocket-time, the closest thing to eternity that there really is.

* * *

They sat in the car, staring out at the lifeless gray ocean. No wind, no surf, nothing out there toward where it banded into the featureless sky, because this relic world of the past had lost even its natural phenomenon.

Already Vicky wanted to be anywhere he wasn’t. And Nash just wanted to be alone.

When they walked out onto the beach, stumbling a bit in the loose sand, they kept a wary distance from each other. A marina stood far up the shoreline, but neither had brought up the possibility of taking one of the boats. They resented the other for the four years wasted. Part of them couldn’t believe that they’d been considering marriage—although that was held with the knife-stab agony of having been so close to it.

A beach without surf, without waves dragging fingers up and down the skin of the earth. Elements trapped together and refusing each other. They had stayed here for too long. You couldn’t outrun time no matter how hard you tried, or how much it hurt.

The sky began to lighten. Tufts of beachgrass sprouted, hair on a newborn’s head. Phantom gulls flickered along the sand, their squawking the voice of the sky. The air itself vibrated, and as Nash and Vicky faced each other tendrils of orange and red reached around and between them—thin at first, then thickening, the ligaments of time itself.

He saw her in the autumn night, leaning against the window as he drove her home. She saw the man sitting across the table in a new city. They danced in the August night.

In a moment of fear, they wrapped their arms around not the targets of loathing they were trapped with, but around the only human comfort in this place. A bitter part of them wondered if that was all they had ever been: gripping to the first readily available comfort in this void.

The wave rushed over them, the inexorable mechanical washing forward of time. Among the oranges and reds emerged a core of purple, a deep sunset kiss settling over and around and in them—removing them from the beach and each other’s arms into futures separate and holding for the other memories and regrets and the hope that the other was doing better than when they’d ended things and that they didn’t hate each other really but were too ashamed to cross the breach into some kind of I-miss-you friendship while remembering not the agony of how they’d ended or even the excitement of how they began and not even the anchor in a new city or driving her home but a night in August. And even after they’d long since lost most of those images, the emotion of that night still held the summation of what they’d been at their best, not erasing their worst but holding against it, a moment and memory resting as a light on a string of them in the dark.

* * *

They hold each other in the shallow cool of an August night, two among many in a backyard arced in string-lights, wrapped up in the music and the celebratory ethereality of a wedding. They dance together like it’s theirs, in a moment that is just itself and what they are within it.

© 2024 by John Stadelman

2311 words

Author’s Note: This story was inspired by Ben Howard’s dark, haunting, beautiful song, “Time is Dancing.” Listening to it, I see lovers at their last dance, knowing that what they have between them is ending, but finding themselves, for the duration of a song, in love again—during which the aftermath doesn’t matter, but instead only what they are, together, in that moment. From there I set them running from that end, defying inevitability by stretching that last moment out beyond its natural limit—until finally giving it up.

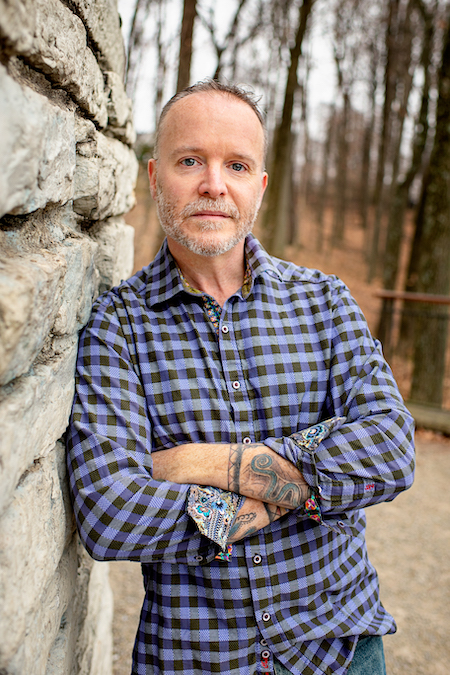

John Stadelman (he/him) is a writer from North Carolina now based in Chicago. He holds an MFA in Creative Writing from Columbia College, and his recent fiction has appeared in Freedom Fiction, Schlock!, Dark Horses Magazine and elsewhere, and he is currently at work on a novel. Although he doesn’t believe in ghosts, he’s pretty sure he saw a Chupacabra one night on the North Side. Stalk him on Twitter at @edgy_ashtray.

If you enjoyed the story you might also want to visit our Support Page, or read the other story offerings.